The Dragon’s Kiss

Of Harmony and the Universal

SINGAPORE: A dragon’s kiss can be deadly, even if proffered in friendship. Though the Chinese dragon of mythology does not breathe fire, is a symbol of strength, sagacity and good fortune, China’s cultivated “friendships” in the crowded Indo-Pacific region can quickly become perilous.

Since the dawn of the millennium, China has been spending billions to make friends in the wider Indo-Pacific - from Australia to Myanmar, South Korea to Indonesia, Maldives to Malaysia -- even rustic, bovinely complacent New Zealand.

And the rest of the world, especially the West, does not like this new China. Or know what to do about it. Since 2000, and till 2016, China has spent at least US$48 billion in hard currency to help foster a benevolent image of itself to its neighbours.

Some 95 per cent of this easily quantifiable amount went to infrastructure projects in these countries, according to a new report by American think-tanks released in Singapore. The study was funded by the US State Department, . The spending on cultural exchanges, city-to-city partnerships, easily around 1,000, Confucius Institutes and other forms of this new diplomacy cannot be objectively quantified.

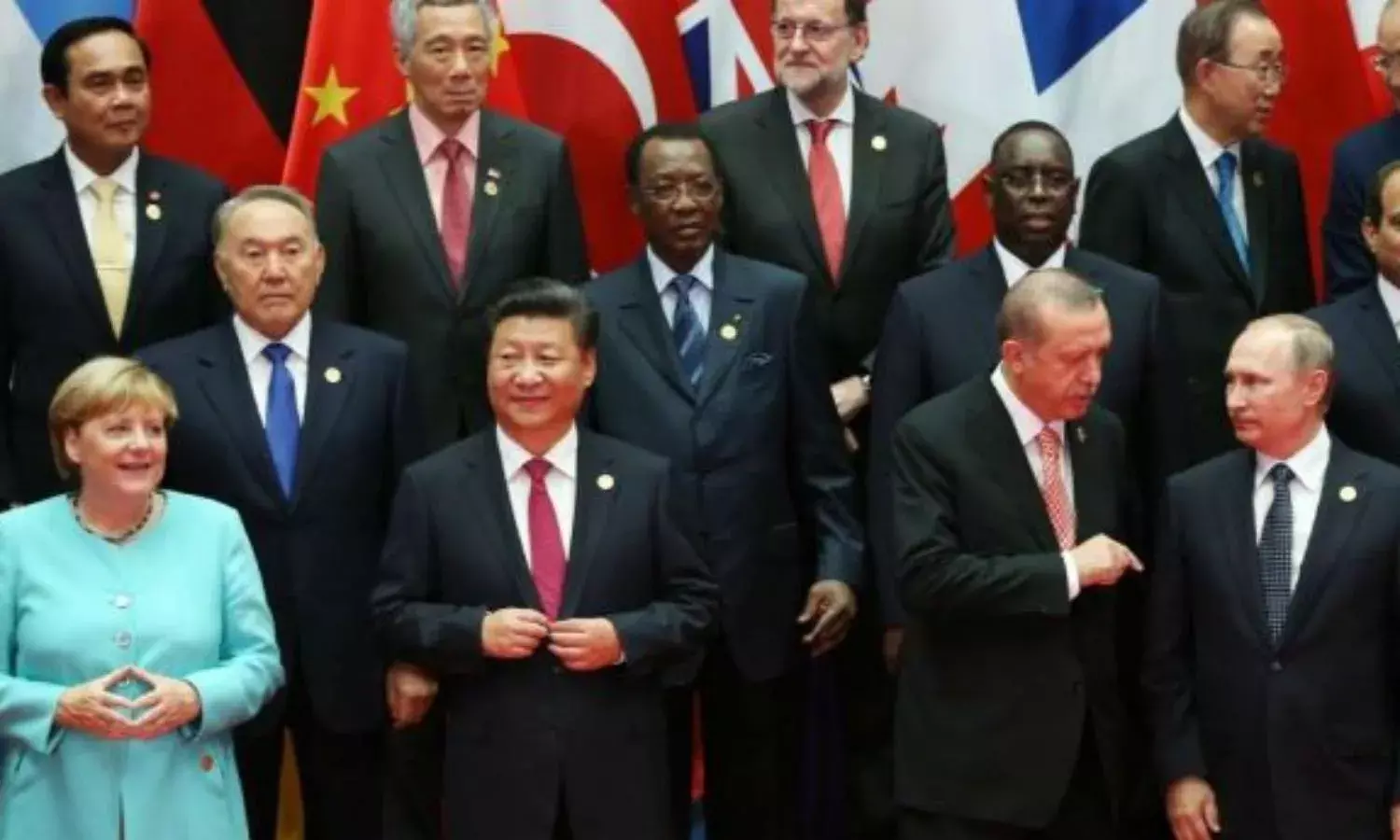

The trend of “soft power” investment by the Chinese is rising dramatically under President Xi Jinping, who at the 19th Party Congress last year in effect declared that China was ready to begin to claim its civilisational place in the world.

In a brilliantly argued speech to the delegates, President Xi laid out the basis for his contention that a “new era” in Chinese development and its engagement with the rest of the world had arrived.

Though to observers his speech may sound militarist, dangerous or alarming, Xi lays out a sound and compelling basis for his contention that China has entered a new phase -- where the previous phase inaugurated by Deng Xiao Peng’s reform ended.

In China, where the communist party is supreme, and where changes in policy have to be supported by rigorous ideology, Xi claimed that China had achieved an intermediate stage of progress from where it can help the world understand and benefit from the values, experience and culture forged by over 5000 years of recorded history, known so far to be the oldest in the world.

Sure enough, there is a pressing need for the rest of the world, especially the West, to understand China.

Certainly, the Chinese government has helped by laying out, as is customary, the basis and logic for its actions in a compelling manner during the President’s address. And no reasonable China-watcher would dispute that the Chinese, who have wrought a miracle by inventing a new form of communism -- one with Chinese characteristics -- has the right to share its wealth and thought, and allay fears as a “risen” superpower.

However, there is a fundamental, irreconcilable contradiction in what can be called the “Xi Doctrine”. To the Chinese, indeed to Communism itself, contradictions can co-exist in foundational thought till the goal is yet unreached.

There may be some special Chinese insight into this communist theory from the Chinese point of view because communism has till now never been able to resolve the two conflicting ideas of social good and individual motive.

Except for the Chinese, who seemed to have resolved the dichotomy, something that eluded Karl Marx, the father of communism or even Mao Zedong, the father of modern China.

In fact, Marx's tortured “soul” may have at long last found rest in China, where Chinese tradition dictates -- more so than in India -- that ancestors be honoured and regular obeisance be paid to their spirits.

Not to do so brings bad fortune and bad luck, the greatest possible calamity in the “characteristic” Chinese mind.

The flaw in communist ideology is painfully obvious: Simply put, why should an individual, forever condemned to selfishness by the reality of “human nature” work for the welfare of society?

In large part, says China, because of the Chineseness of the Chinese people. That the Great Chinese Experiment has been so successful is no accident. One part of Chinese character is the cultural instinct to put society over individual, family over progeny, harmony over discord or fanaticism, and tradition over novelty.

Herein lies another contradiction in the Xi Doctrine: Chineseness or Chinese “character” cannot be separated from tradition, precisely because it is so old and appealing at so many different levels.

In its attempt to homogenise Chinese dialects and culture in the interests of nationalism, conformity or unity, the Chinese government is doing violence to the Chinese character by erasing the dialects. The next generation may well grow up oblivious to diversity: in the belief that Hakka culture is no different from Hokkien, or Cantonese from Teochew. There are other, more insidious attempts to wipe out Chinese history.

There has been a largely successful attempt to erase the collective memory of the modern youth who have no knowledge either of the Celestial Emperor or the trauma of the Tiananmen massacre. In 1989, the great “People's” Liberation Army of peasants, workers and intellectuals alike -- since Mao seen as the unshakeable protector of the Chinese people -- was ordered to kill young boys in broad daylight.

The Chinese communist party can co-opt, or put another way, utilise tradition to achieve its own ends: the Chinese people are perfectly willing participants as long as the fruits of such a strategy are readily apparent, as in the Chinese economic and infrastructure“miracle”.

The USSR wrenched the old Russian Orthodox Church from its roots in an ancient, ritualistic tradition and homogenised a diverse, artistic people.... and spectacularly failed. The Chinese challenge will be to avoid that fate.

The portents of the past few years are not good, but can easily be reversed.

China's aggressive military build-ups have already sown discord in a region which has owed its peace to the global security framework and the rules-based order that the victors of WWII put in place. Without the US Navy patrols, supported in joint or solo operations by the Indian Navy for decades, the trade routes that enabled China's rise would have been much less safe.

For a resurgent China, external aggression is not a threat, and the rest of the world should get used to a big power occupying more geopolitical space. The danger lies in internal discord if the momentum slows.

Organised religion has never had a hold on the Chinese people. Religions like Buddhism or Islam are imports which gently slipped into the vast pool of tradition. Native religion like Tao-ism, even where a “messiah” is identifiable, does not excite extreme positions. Lao Tze, the man who wrote Tao Te Ching, was fittingly, a librarian at the Imperial Palace. The Middle Kingdom has always found the Harmonious Middle between Heaven and Earth.

Where Buddhism, an Indian export, matters is only that it found fertile ground where it could be nourished and grow. The Chinese were Buddhist in spirit, even without the doctrine. The Middle Path is simply collective wisdom, Easily, Confucius, as the Chinese government is well aware, is far more central to Chinese character than any other figure: unlike similar figures elsewhere, the Chinese sage did not examine God or Reality: his most eloquent analects have to do with Society and how personal ethics interact with social good.

As a people, the Chinese, unlike Americans or Hindus, believe individual values should ever be subject to social good and harmony.

China's aggressive “financial diplomacy” has caused concern among its neighbours like Australia, Singapore and others. Australia recently passed a law, clearly aimed at China, to prevent foreign interference in its affairs. In Sri Lanka, where the government was unable to service massive loans, China forgave debt in exchange for a strategic port.

Apart from suspicious neighbours, there are at least two other factors for China to ponder as the Xi Doctrine becomes more and more central to Chinese policy at least till 2035, when, Xi says, China will pursue a much more active, “high-spirited” role in world affairs.

The first is that, though Xi seems to have been able to effortlessly command the respect of all three of China's power centres, the party, military and the Politburo Standing Committee without ruffling any feathers, he has one great drawback: He is the first Chinese President to have not been anointed.

Both his predecessors Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao were hand-picked by Deng Xiao Peng before he died.

The other great loss is in the death of Singapore's Lee Kuan's Yew, who was a moderating influence on China and its most respected interpreter to the West.

In fact Lee, whose importance is under-appreciated both in China and Singapore, provided the model for Deng's great reform.

On a visit to Singapore in 1978, Deng was dumbstruck that “Chinese people” could achieve so much in such a short period. He also adopted the Chinese “characteristics” model from Lee, who eschewed the western liberal model for a more limited form of democracy and achieved great success.

But every nation, it can be said, is a composite of its culture, tradition and history. Perhaps the “Chinese characteristics” model is only particular to the Chinese people?

For a wider dissemination of its wisdom , perhaps China should embrace and spread that component of Chinese values that is “universal'. Or at least preserve the Chinese precept of Harmony.