'Policies Not Politics': A Year Since the Giant Protests in Bangladesh

Road safety issues were only the tip of the iceberg

“If I lose, it will not mean that it was impossible to win.” ---Che Guevara

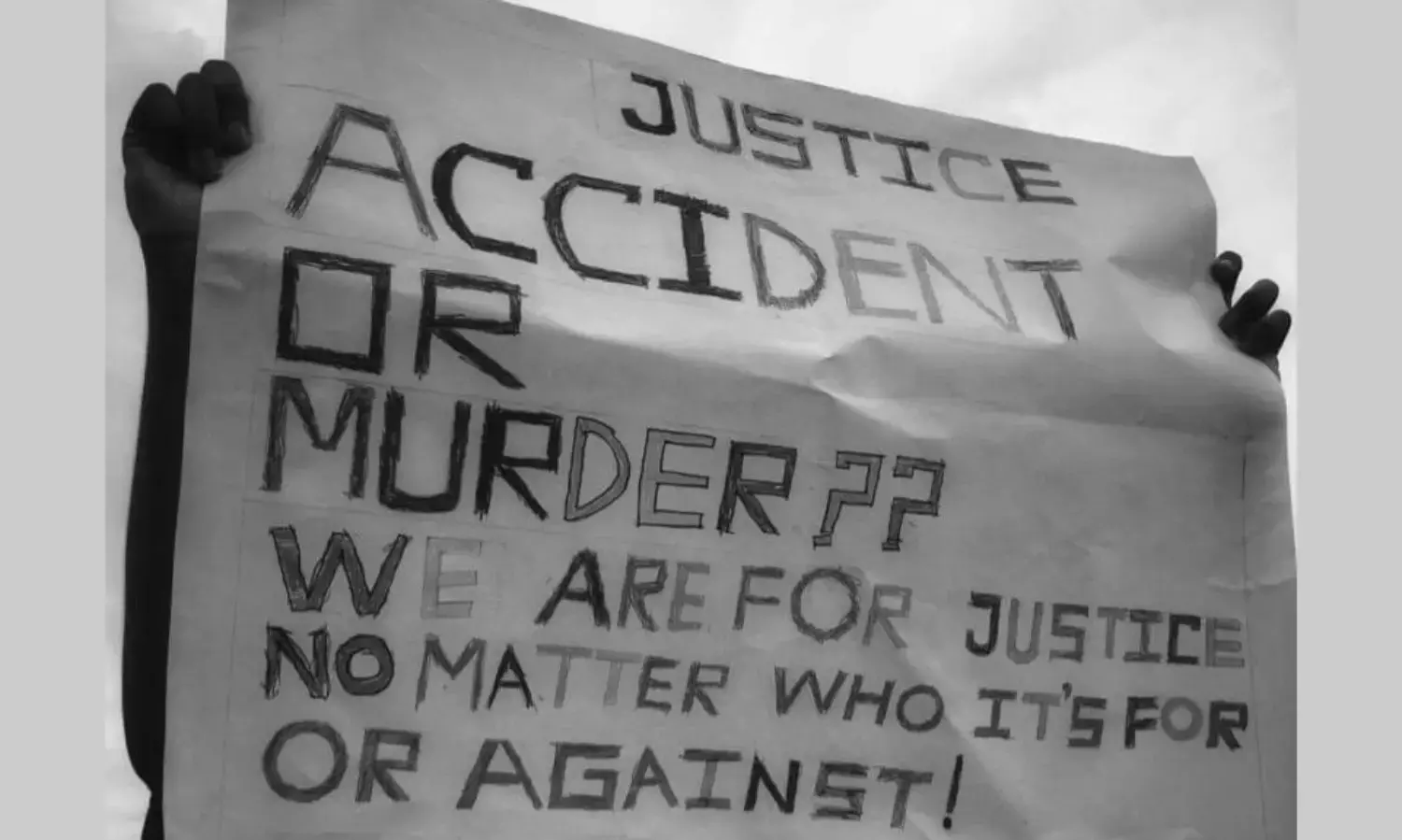

NEW DELHI: It’s been almost a year since students took to the streets protesting the loss of two of their fellow students hit by a speeding bus in Dhaka on July 29, 2018. As students were rushing to go home after school, a bus driver lost control of his vehicle and took the lives of 18 year old Abdul Karim and 17 year old Dia Khanam Mim, and wounded several others.

It wasn’t long before scores of students gathered and blocked the road, not to express their grief but to demand improvement and safety on the streets. Shipping and Transport Minister Shahjahan Khan’s insensitive statement, in which he compared the incident to a road crash in Maharashtra, changed the scenario.

Khan laughingly brushed the accident aside, saying “33 people were killed in Maharashtra recently but do they talk about it the way we do?” His remark didn’t go down well with the citizenry and he was roundly criticised. A video of his comment went viral on social media sparking massive nationwide protests. Students demanded the minister’s resignation despite his apologising for the comment.

The protests were widely reckoned to be peaceful. The students protesters’ demand was safety on the roads for every Bangladeshi. They issued nine demands including the construction of speed bumps on dangerous roads, the enforcement of laws requiring licences, and even the death penalty for reckless drivers who caused death. Following directives from Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, Home Minister Asaduzzaman Khan Kamal said their demands would be met.

The protest crippled the city, putting the government under pressure. A new draft of the Road Transport Act 2018 was rushed through which promised to consider the death penalty for deliberately causing road deaths. Law Minister Anisul Huq told the media that if police investigations found drivers to have deliberately caused someone’s death, they would face the death penalty under the country’s penal code.

The protest soon spread outside the capital Dhaka. The protesters, mostly students aged 13 to 19 were later joined by university students. These volunteers blocked major roads and demanded that traffic laws be enforced. Teenagers were seen enforcing traffic laws on their own, asking for drivers’ legal documents as well as the fitness certificates of vehicles throughout the country.

Students also kept an emergency lane open for ambulances. They were seen stopping cars travelling on the wrong side of the road. According to reports in the local media, the students even caught police officers without a driving licence.

Soon enough, parents and guardians were seen joining their children and students in the streets in solidarity and support. They also provided food and water to the protesters.

Students all over the world came to support and solidarity. These are students from Sweden standing with Bangladeshi students

Mohammad Yunus, a Bangladeshi civil society leader, remarked in one of his articles ‘You Are Bangladesh’ about the students’ movement that: “There was no sign of childishness in anything they did. They looked professional, and acted like it. I saw their seriousness, their maturity and determination. They were careful to do the right thing, so that their message arrived.”

Bus services were called off from their duty. The government declared that all educational institutions would remain closed countrywide on August 2, 2018.

The governing Awami League quickly retaliated through the law enforcement authorities and its student wing the Bangladesh Chhatra League (BCL). Police reportedly used tear gas and rubber bullets, injuring hundreds of teenagers, while the authorities denied these reports. BCL goons were seen vandalising vehicles and beating up unarmed peaceful student protesters in the presence of police.

The BCL is also blamed for attacking photojournalists, snatching their cameras on the streets, and targeting phones and cameras for destruction.

Many local reports suggested media suppression. Slogans such as #WEWANTJUSTICE, #ROADSAFETY and #BANGLADESHSTUDENTPROTESTS went viral on social media.

Hundreds of teenagers were targeted via their social media accounts for their support to the movement. The police detained students who had posted videos and photos of the protests.

There were rumours that pro-government groups killed several students and raped four female students.

Students participated in the demonstrations were terrified of arrest and soon started deleting any messages of evidence or support that they had posted online. They described the situation as chaos, and said anyone with a camera had become a target for the authorities and BCL cadres.

Much of this fear comes from Section 57, a law passed 13 years ago in Bangladesh.

Section 57 of the Bangladesh Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Act authorises the prosecution of any person who publishes, in electronic form, material that is fake and obscene, defamatory, “tends to deprave and corrupt” its audience, causes or may cause a “deterioration in law and order”, prejudices the image of the state or a person, or “causes or may cause hurt to religious belief”.

The ICT Act was approved during the Bangladesh Nationalist Party led coalition government with the Jamaat-e-Islami in 2006 and has been misused recently. Many experts believe that the act is detrimental to free expression. Scores of people have been detained and arrested under Section 57 in Bangladesh.

Rahat Karim, a freelance photographer beaten by BCL men while capturing the protest

This post was circulating over social media platforms during demonstrations last August

The arrest of Shahidul Alam, an award winning photojournalist made international headlines. Alam was charged under Section 57 for his comments about the student protests during an interview with Al-Jazeera. He was jailed for 107 days and was badly beaten while in custody. Alam was released in November 2018 after being denied bail four times.

“Even the government of Bangladesh acknowledges that the current Section 57 of the ICT is draconian and needs to go,” according to a statement by Brad Adams, Asia director at Human Rights Watch.

In response to the student movement the national authorities launched “Traffic Week”. In the first round of traffic week the police lodged more than 50,000 cases against different vehicles and took action against 11,000 drivers for traffic violations. The week-long programme was organised by the Dhaka Metropolitan Police (DMP) to take legal steps against unfit vehicles, drivers without licenses and other traffic offenders, including pedestrians.

Since March 2019, the traffic department of the DMP has been observing traffic week every month to improve adherence to traffic rules. The Bangladesh Road Transport Authority has also taken measures to reduce traffic accidents and get rid of old vehicles for safer roads.

A draft law was passed in a cabinet meeting headed by PM Hasina, amending the Road Transport Act of 2018. The cabinet approved a maximum penalty of five years in jail and a Tk500,000 (about USD 6,000) fine for fatal road accidents.

The protests continued for nine days until August 8, 2018. Allegations of gross human rights violations were levelled against the Sheikh Hasina government. The prime minister rejected all the allegations and said that “infiltrators” were trying to benefit from the students’ movement by spreading rumours and unleashing violence. “We are worried about the fate of the movement as Bangladesh Nationalist Party and Jamaat-Shibir activists have already infiltrated it to realise their agenda of ousting the government,” she stated.

But most observers believe the BNP was not instrumental in launching the protests, which were spontaneous and non-party-political. “The students have showed us the state is in need of repair,” was the response to PM Hasina’s allegation by BNP secretary-general Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir.

The misgivings about Section 57 and Alamgir’s comment point to broader underlying reasons for the widespread anger. On the face of it the movement was for safer roads but according to experts the concerns extended deeper. Ali Riaz, a professor at Illinois State University, wrote at the time that “the protest reflected broader issues including the absence of accountability in governance and the absence of rule of law… Whatever happens to the movement in the coming days, however it ends, the younger generation has demonstrated that they can challenge the prevailing culture of fear,” underlined Riaz, adding that “their courage will have an indelible mark on Bangladeshi society and politics.”

Another South Asia expert from the Washington-based Woodrow Wilson Center, Michael Kugelman believes that the protests were an expression of longstanding, pent-up anger about the government and its policies on the whole. “It's hard to imagine that the mere issue of traffic safety, important though it may be, could spark such a widespread and sustained period of dissent,” Kugelman told Deutsche Welle.

“The road safety issue is the straw that broke the camel's back; these large protests were rooted in much deeper and complicated grievances.”

The likes of this movement had never happened in the history of Bangladesh since it gained independence from Pakistan in 1971. Thousands of students showered the roads throughout the country to support the movement. Filmmakers, actors, parents and teachers were all among the supporters. The level of protest and counter-violence caught nearly everyone by surprise. International bodies such as the UN, UNICEF, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International and several others voiced their concern.

While researching this essay I tried to contact a few students who were part of the demonstration, but none responded. I realised that must be because of Section 57 of the Bangladesh ICT Act. Many Bangladeshi students had tweeted that they were afraid to speak out. Many removed their posts about the protest. Still some tweets remain: