Brazil’s 19th-century Response to a 21st-century Pandemic

Past and present mix

SÃO PAULO/ CAMBRIDGE: As the death toll in Brazil nears 30,000 people and is likely to remain on a steady and fast escalade over the next few days, many believe the arrival of the pandemic during a political and economic crisis has turned to looming disaster.

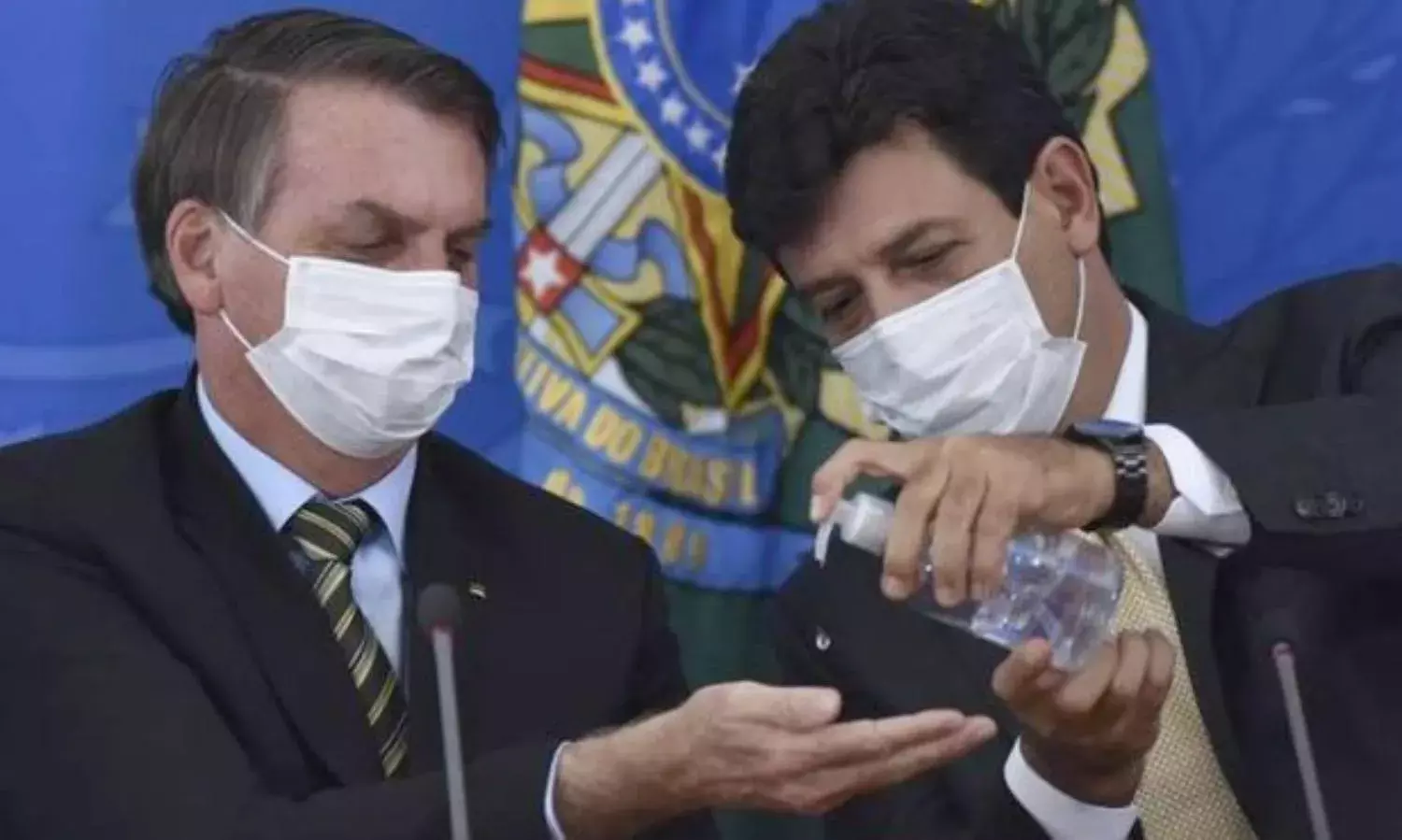

Nonetheless, Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro - who called the virus “just a little flu” - and his supporters are still dedicating their time to organising protests against isolation measures to contain the spread of the disease.

But Brazil’s history tells us it is not an unpredictable scenario: such reactions owe a lot to the nation’s slave-owning past, and the way its elites came to handle economic pressures.

58% of Brazilians still live within 200km of the ocean - a heritage from colonial times. As the exploitation of fertile lands for agriculture grew with demand for its commodities (sugarcane then coffee in the 19th century) Brazil became the biggest importer of enslaved labour in the continent, accounting for 46% of the traffic in slaves from Africa to the Americas.

In 1849, with Britain pressuring the Imperial Government to abolish the slave trade, ships rushed to the Brazilian coast filled with enslaved captives from Africa, meant to fuel the booming coffee and sugar farms, the demand for house servants, and urban commerce.

It is still possible to feel this heritage. Brazil has the most significant African diaspora population in the world, and the social indices still show they hold precarious jobs, in inadequate housing, education and health conditions.

In 1849 one of those slave ships, inbound from Havana after a stop in New Orleans, docked in the old colonial capital of Salvador and let loose some mosquitoes from Africa. Today, Aedes aegypti with its black-and-white stripes is well known to Brazilians as a carrier of dengue fever, zika and chikungunya. On 30 September 1849 however, it brought something unknown to them: the yellow fever.

Six weeks later, on 15 December 1849, the local authorities sent word of the problem to the Imperial Government in Rio, and the nation's best doctors at the Academy of Medicine got together to discuss the matter. They considered that Brazil had a “proverbial healthiness”, as one doctor called it, while yellow fever was believed to be something that only prospered in much warmer climates. Such a plague would not flourish in our pleasant weather.

On 23 March 2020, Mr Bolsonaro said the virus would not survive in Brazil's weather as it had in Italy, with “a climate rather different from ours.” The virus had been first reported in the country just 26 days earlier.

History and description of the Yellow Fever Epidemic that raged in Rio de Janeiro in 1850

As the ship from Havana followed the coastline down to Rio de Janeiro and the epidemic spread, with hundreds of sick people reported in the capital and other coastal cities, British diplomats were lobbying the Imperial Government. They suggested that quarantine procedures such as closing off ports would be senseless in the fight against yellow fever, arguing that adverse sanitary conditions were to blame for the outbreak.

Meanwhile Yellow Jack, as the disease was nicknamed by the British, was spreading rapidly through the capital’s urban tenements.

With doctors suggesting artillery shots and fires to cleanse the air, the next step would be the destruction of these tenements. The freed and runaway blacks who lived there would move to the hills of Rio de Janeiro and build the first favelas (slums). From 1855 onward these places, unsuited to accommodate a large population, would become a recurring epicentre of cholera outbreaks due to a lack of basic sanitation provision.

On 26 March 2020, Mr Bolsonaro stated that the spread of the epidemic wouldn't cause many deaths, considering that the average Brazilian was used to diving into sewage water during floods, a proof of “innate resistance” that should be studied.

With the epidemic ravaging the imperial capital, those who could afford not to work fled into self-isolation in Petrópolis, a tropical and mountainous Versailles just a few hours away from Rio. They kept their slaves working in Rio - noblesse oblige.

Although Africans and Afro-descendants were more resistant to the disease, most likely by accumulated immunities, in truth the rhetoric of the time needed to find ways to defend the continuity of trade and wage-work.

The statistics in Rio did not consider that slaves and free Africans were, as their descendants still are, a population with less access to quality health services. Underreported cases, the denial of information and poor living conditions defined their reality, and define the reality of those who live in Brazil's favelas today, who are having to deal with the Covid-19 crisis on their own, in scenarios where they are about ten times more likely to die from the infection than their counterparts living in better conditions.

Protecting trade became a priority, and in 1850 the ports were kept open and the death toll kept rising, with around eighty people dying per day in January, February and March. Just a few weeks ago, the city of Blumenau in the southern state of Santa Catarina became a global symbol of denial when it decided to reopen commerce against the recommendations of the World Health Organization, with Covid-19 cases spiking 173% after the measure.

In Rio as the fever death toll kept rising, and even the Emperor's son died, the Hygiene Junta discussed a possible cure. Drawing on reports by a French doctor who had treated the fever with quinine sulfate years earlier during an outbreak on board the steamship Gomer, the Imperial experts believed they had found an answer.

Without proper studies and testing, the treatment was implemented and instantly began to fail. People with comorbidities, and there were many given the lack of basic sanitation provision to poorer communities, were undoubtedly the ones most affected by the fever.

Last month Mr Bolsonaro, having ordered the army to produce chloroquine pills, went on to say in a public address that this medication should be used to treat Covid-19, although there isn’t to this day a consensus on its effects.

Even after studies of its efficacy were cancelled - after the death of a test subject in Manaus - Bolsonaro’s supporters have pressured for its extensive use as a “cure” that would allow isolation measures to be ended, basing themselves on the success a few French doctors obtained in an isolated scenario in Marseille. As a consequence chloroquine has disappeared from the pharmacies, and those actually in need of the medicine have difficulty finding it.

In 1850 as Yellow Jack seemed to be easing its grip, the official death toll was of 4,160 people in a city of 166,000. But the real figures were believed to be much higher, motivating the creation of South America's first service of health statistics the following year.

As an answer to the epidemic - and to British pressure - Parliament abolished the slave trade that year and deemed the measure sufficient.

Epidemics have since become a focus of studies in Brazil, from 19th-century doctors’ researches to panoramic works such as Sidney Chalhoub’s Feverish City. The constant struggles with such diseases have been the result of political decisions in the field of health, and an absolute disregard for the most impoverished communities.

In the following decades, as no vaccine was discovered and no extensive public policy plan was laid, yellow fever would return in wave after wave with devastating results, until a vaccine was found. Countrywide campaigns would succeed in eradicating it only in 1942, almost a hundred years later.

Although today scientific advancements allow for faster vaccine development, in today's Brazil the authorities continue to ignore the warnings of 1850, while following its mistakes with diligence.

With the government’s continued failure to organise a broader system of financial aid, food supplies and improved sanitation provision, especially for those in the favelas, we are led to ask ourselves, will the Covid-19 crisis in Brazil become the biggest historical reenactment on the planet?

Paulo Henrique Rodrigues Pereira is visiting researcher at the African-Latin American Research Institute and the Department of History at Harvard University and Caio Henrique Dias Duarte is researcher at the Law School of the University of São Paulo