‘When Will I Go To My Country?’

She mentions instances of her friends being dragged out of their homes

Every day, *Mohammed Shoaib, a 30 year old daily-wage earner finds himself in no man’s land, with no place to call home. For nearly a decade he has lived with his family at a refugee camp in Kelambakkam, Chennai.

“We were given Aadhar cards but they were taken away by the government during the second wave of Covid19. Now we are just left with a UN card, which helps in dealing with the police and local administration. But it doesn’t help in getting ration, health checkups or work in the area,” says Shoaib, who grew up in the town of Maungdaw in Rakhine, Myanmar.

The story of Shoaib and 80 other “stateless” people in Kelambakkam might be enough to show how refugees in India live amidst a crisis of identity.

Several waves of bloodshed over decades, most recently in 2017, targeting their homes compelled the Rohingyas of Myanmar to seek refuge in neighbouring countries. According to UN figures over 1 million Rohingyas now live in Bangladesh, 92,000 in Thailand and 21,000 in India, among other countries.

Local estimates have it that some 40,000 Rohingya refugees live in various camps and slums in a number of Indian cities and towns, including Delhi, Jammu, Hyderabad, Nuh and Faridabad.

In 2019 Amit Shah, home minister for the Government of India, reportedly told Parliament that Rohingyas would not be given Indian citizenship as they had “infiltrated” through Bangladesh and did not enter India directly from Myanmar.

The Citizenship Amendment Act then under discussion and promptly passed excludes from its purview Myanmar, a neighbouring country with the worst refugee crisis in recent history, as well as Muslims from its provisions for expedited citizenship. Petitions to the Supreme Court challenging its constitutionality remain unheard.

In Chennai the refugees from Myanmar live in dilapidated camps - shanties of cloth and tarpaulin pulled over bamboo structures, barely able to withstand a storm at the Kelambakkam cyclone shelter. It was earlier a Village Administration Office.

“There is not enough space to live here. It gets very dirty when rainwater floods our houses regularly during the monsoon. Mosquitoes also breed here. So, we require a larger space,” Shoaib explains.

Two schoolgoing boys, Sayyed Mohammed, 12 and Sadi Islam, 13 recalled the frightful incident of a snake getting inside their home a few months back.

For Rohingyas, once friendly neighbours at the camp have turned hostile now.

“They stay unhygienic due to which various diseases like malaria spread. Our children used to play together but we do not let them anymore,” says Dinesh Paul, 37, a neighbour who has fenced his house as mark of a boundary.

Commenting on the role of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, a senior official requested anonymity. “UNHCR doesn’t provide shelter, education and so on but we ensure that the local government does.

“Since 2017 we have narrowed down some places to shift Rohingyas, but the children are enrolled in nearby schools and have settled down there. So, they would be at a disadvantage if we shift them now.”

Resentment is not new for the Rohingyas as they used to face it continually back home. So it was for the first few months after they landed in Chennai, in 2012, say Shoaib and his family.

“We spent the first five days on the road as we did not know Tamil. Then we managed to rent a house in Kalaimani but under pressure from the locals, the landlord asked us to vacate it after six months as we are not from this country. Later the police shifted us to near the Kovalam beach,” says *Taslima Khatun, Shoaib’s partner.

She mentions an incident by Kovalam beach where a local faced backlash from other locals for providing them with basic rations.

After moving again a couple of times, the family were finally shifted to the Kelambakkam shelter with help from the UNHRC, which also ensured that the children were enrolled in the nearby Kelambakkam Government School.

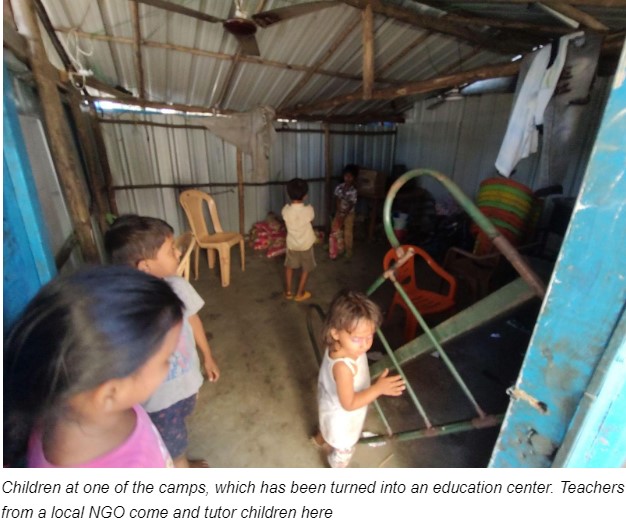

Around 30 children at the camp, some as young as 6 years old, now attend school.

They say they feel out of place, at times.

“Junior school teachers call us ‘Burma Kaaris’. So, eventually I stopped telling people that I am from Myanmar. Only my best friend knows it,” says *Rukhsana Salma, a ninth-grader.

Rukhsana adds that people in Chennai do not usually discriminate against their “Muslim identity” the way people do with their compatriots in other Indian states.

“People here provided us ration and basic necessities regularly during the first and second waves of Covid19. The government here has given me shelter, electricity and other facilities. I have accepted that this is not my country no matter how much I love it. I feel ashamed to ask for more than we are getting,” she says, recalling the aid provided by locals and NGOs during the multiple covid waves.

The 15 year old aspires to be a doctor.

Most men here work as ragpickers - some were trafficked by the kabadi mafia from Bangladesh. Others work for a daily wage as helpers in nearby warehouses and restaurants or delivery boys for nearby shops.

“I earn around 6000 a month after every day’s toil, which is very little to manage a family of four people,” says Nafisa Ali with her spouse, Abdul Nadeem.

While a few women help their husbands collect scrap, most of them work to raise their families.

Camp residents want the UNHCR to intervene and have their Aadhar cards returned. At present they only have their UN Refugee and Burmese identity proofs with them.

Asked about the issue of identity cards, the UNHCR official pointed out that since Rohingyas do not hold Indian citizenship they are not eligible for public welfare schemes.

However T Ramakrishnan, a reporter at The Hindu who has covered the Rohingya crisis, held different views. He said, “It is the responsibility of the state and UNHCR to arrange better housing for them.”

Meanwhile Syed Shahezadi, member of the National Commission for Minorities,denied any role for the commission in providing assistance to the Rohingyas.

“The commission only looks out for Indian minorities, not from Myanmar and Bangladesh,” she explained.

Rohingya Muslims were forced into a state of precarity by the Myanmar state towards the end of 20th century.

Some years after the death of U Thant, the Myanmar Citizenship Law enacted in 1982 did not acknowledge Rohingyas as an “indigenous ethnic group,” and government officials seized their identification papers.

That was the beginning of their relentless and systematic ethnic cleansing from their homeland.

In 2015, a controversial National Census exercise excluded over 1 million Rohingyas from its register. The government of Aung San Suu Kyi cracked down on them brutally, forcing many to escape on foot and more perilously, by sea. The UNHCR stated that over 2,000 Rohingyas had been precariously found at sea, calling it the Andaman Sea and Bay of Bengal crisis.

A fresh scale of racist government crackdowns in 2017 made matters much worse, when the Tatmadaw, the Myanmar military, perpetrated large scale ethnic cleansing, on the claim that it was responding to the actions of a Rohingya resistance group called the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army.

Many more such armed resistance groups of many ethnicities have sprung up in Myanmar since the last coup d’état in February 2021.

Back in 2012-13, when Shoaib and his family arrived in India, refugees reported that junta officials had demanded they sign up for identification cards stating that they were “Bengali”, to suggest that they were undocumented immigrants from Bangladesh.

But Rohingyas have a recorded historical presence dating back centuries in what is now western Myanmar.

A 2019 report by Fortify Rights said that a National Verification Card issued by the Rakhine State Immigration and Population Department included questions like “Which border did you enter from?” and “How did you come to Myanmar?” It required Rohingyas to register themselves as Bengalis.

Rameez Khan, 28, a daily-wage worker and former native of Taungup city, Myanmar, confirms this.

Dressed in a checkered multi-coloured lungi and blue t-shirt he says, “We had to keep a notebook called ‘census paper’ in our homes, which the police would check regularly. Once I had an accident and went to Bangladesh for a checkup, but my name was redmarked by the police, which meant that if I go back I would be jailed. In the jail, they beat me heavily.”

Just then Shoaib receives a video call from his aunt, who lost one of her legs after stepping on a landmine while fleeing in 2017. She currently lives in Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh, the largest group of refugee camps in the world.

Burning down their homes, perpetrating excruciating torture followed by widespread murders, looting, and systematic sexual violence against women, memories of the Myanmar army still send shivers down the spines of many refugees.

Around 340 Rohingya predominant villages were partially or totally destroyed by the Burmese security forces, leading to an unprecedented mass exodus, according to a Human Rights Watch report published in 2017.

“My neighbours were locked up inside their homes by the military and the house was set on fire,” Taslima recalls. She mentions instances of her friends being dragged out of their homes by soldiers and raped.

Shoaib shares they had to part with almost all their savings to pay the agents to get out of Myanmar. “We reached Cox’s Bazar but were not welcome there, and the agents in Bangladesh gave us three options: India, Nepal or Pakistan. We chose India as it was the cheapest, for one lakh kyat, and paid them.”

After spending years in India, Shoaib and the elders at Kelambakkam want to return. But they want their government to promise them rehabilitation along with other facilities. “Only if the Myanmar government assures us of their full security and good behaviour to us, will we go back,” says Shoaib.

“When will I go to my country?” said Rameez with a grim expression on his face. He explained that Rakhine belongs to Rohingyas as much as it does to Buddhist communities. “We always wanted to stay together with them. Even now, we want the same.”

Asked about the possibility of repatriating Rohingyas the UNHCR official said, “Efforts have been made through talks with the Myanmar government but no agreement has been reached so far.” He added that if they wish to return they can do so voluntarily, but the UNHCR cannot commit the illegal act of refoulement, or force them to return.

*Names changed to protect identity