Ethical Bankruptcy in Tackling Domestic Violence

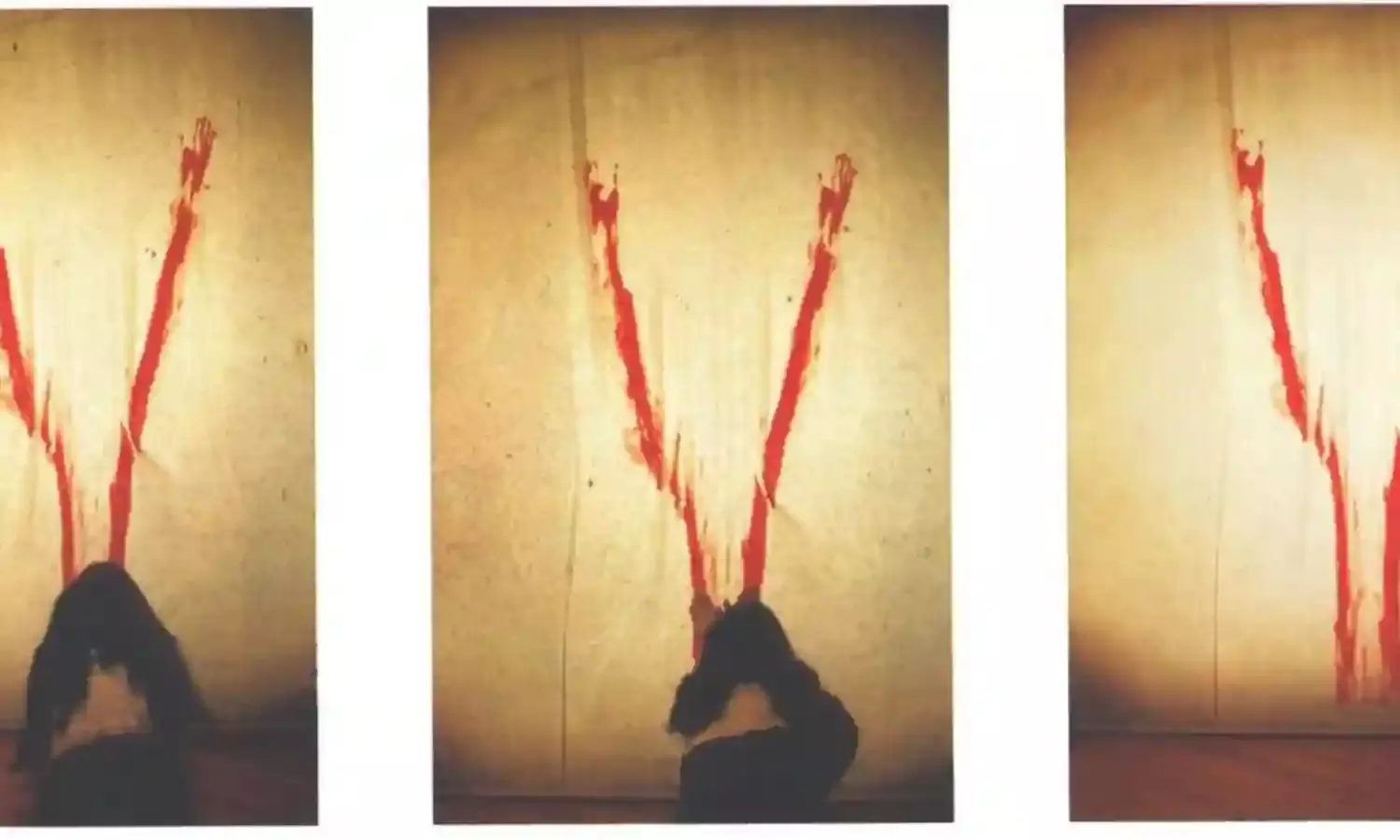

Eventually, gravity does its work, where violence will meet counter violence

Violence is never linear, homogenised or as banal as it appears. On May 30, agencies carried a news report about a woman in Lakhimpur district, Assam, who killed her husband and appeared at the local police station with his severed head. Guneswari Barkataky not only killed her husband but also surrendered herself for the crime she had committed.

What does this tell us about the femininity of violence? Or the complications and troubles associated with the victim, who not only committed the crime but also chose to face accountability for her actions?

And where does the debate on martial and domestic violence feature in this particular incident, where the stakes of women are high in a brahamanical-patriarchal, misogynist and heteronormative state?

Centuries of covert and overt forms of violence on women do not justify this crime. The everydayness of the systematic oppression of women will not make her a martyr for this crime. Nor would the invisibilisation of narratives around marital rape, emotional and mental abuse call for such an intervention.

What would? What options or platforms are we creating to help women push, cut ties and break out from the cyclic process of violence and apathy?

The coldness of violence that women often experience in their personal, intimate and professional lives – a lack of attention, lack of appreciation for managing and running enterprises and families without being paid, unequal power relationships defining the access and availability of opportunities for social-cultural, political development, of emotional, physical and sexual labour… Is society compensating enough?

Then we have women who are at the peripheries, married women that work in homes, domestic workers, and women involved in prostitution, women affected by caste-based occupations, women who work on farms and in medium and large factories still, and many others who have spent entire generations facing social-psychic-physical violence.

On occasions when they have had enough of it, we see examples of women aiming to break out of their disturbing and painful lives: Nangeli, Jhalkari Bai, Phoolan Devi, Bhanwari Devi, Sheetal Sathe: glaring into the debauchery of the patriarchy-state nexus, they have marked the boundaries of their patience.

Assertions and retaliation are exercised when a person or community undergo decades of violation and subjugation. Eventually, gravity does its work, where the violence will meet counter violence. It is then that we should rely on our judgement to not simplify these acts, but to dig deeper, keeping in mind that counter violence broods on a history of violations, ill treatment, neglect and ignorance of women’s needs, to favour the constellation of governance structures nationally and globally.

Domestic violence therefore, must not be about the act of physical violence alone. Other forms of subtle marginalisation are defined under different acts in the Indian Penal Code.

Consent in sexual relationships, protection of women against desertion, giving equal rights to women under domestic partnership even when the couple is unmarried – so on and so forth – are all acts that recognise women’s vulnerabilities, acknowledging the everydayness of events seen as harmless, which over a period lead to overpowering and hysteric incidents of violence.

The leadership of Ambedkar, Savitribai Phule, Jacenda, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar in more contemporary times, has shown that women’s wellbeing has to be at the heart of governance.

More importantly, do not criminalize women for protecting themselves: a right mandated by the Constitution if the frameworks of government are failing to be inclusive, compassionate and protective of the interest of women as equally lawful citizens.

Cover image – Ana Mendieta, Untitled (Body Tracks), 1974