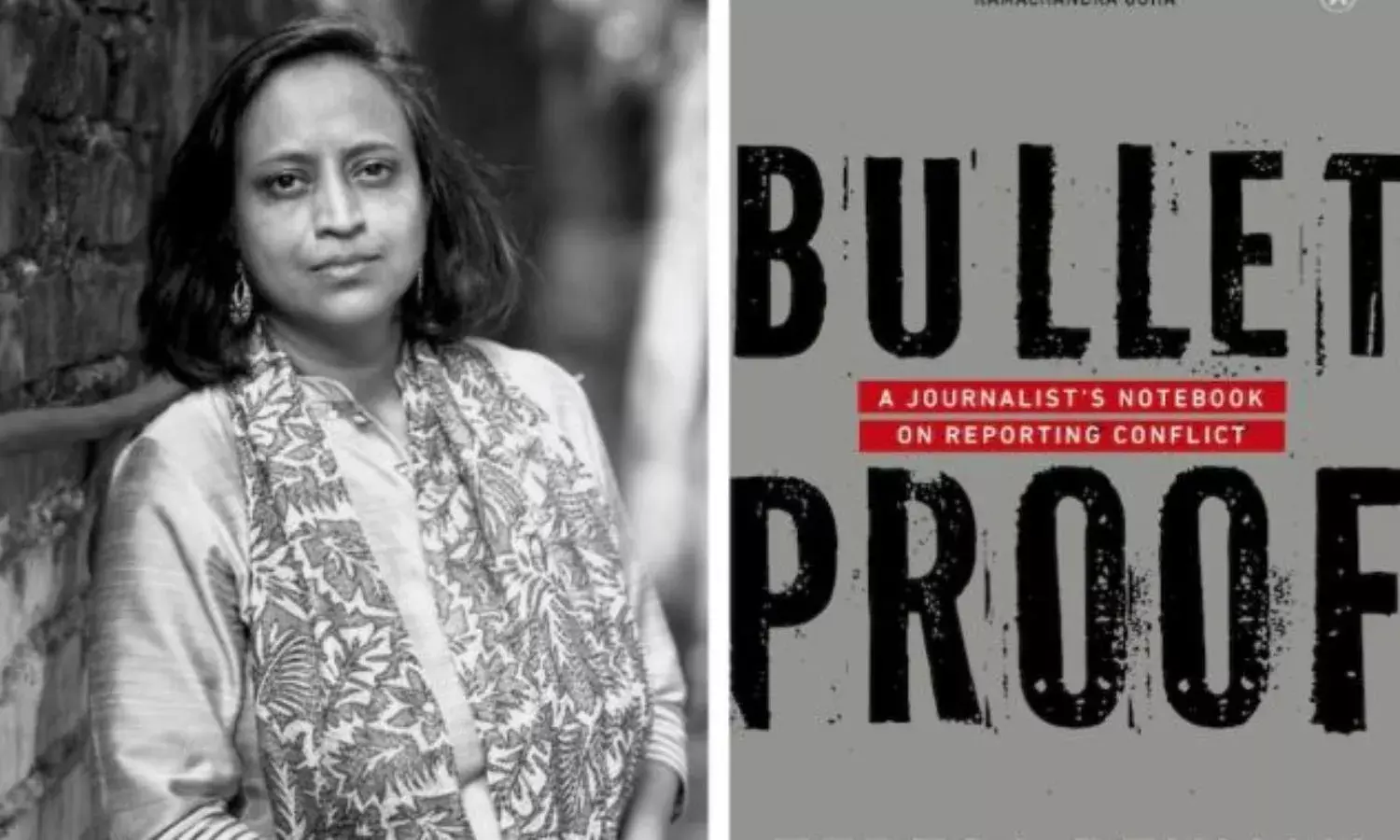

‘Reporting Conflict Can Spring Surprises at Every Step’

Interview with journalist Teresa Rehman

GUWAHATI: What did it mean to be a conflict reporter in trouble-torn northeast India? Award winning journalist Teresa Rehman, who covered the region when the insurgency was at its peak and many human rights violations took place, has created the book Bulletproof to narrate her stories. To know more about her and the book, we caught up with Rehman.

The book’s name hints at the level of difficulty of covering conflict in the northeastern region. And it was even more difficult when you started journalism in the 1990s. What exactly do you try to tell in the book?

Bulletproof is the deeply personal journey of a first-generation journalist doing her duty, battling various odds, in one of the world’s most under-reported regions. It has witnessed several decades of violent insurgency and reporting from the region is a challenging task.

When I started out in journalism and began reporting hardcore conflict, I was on my own, with only my pen and notebook and sometimes my kids for company.

Reporting conflict can spring surprises at every step. And though I am a journalist trained at one of the country’s premier institutes, I was not aware of the dangers, fears lurking behind a journalist reporting conflict.

I was on my own, without any support system or the bulletproof jacket commonly used by foreign journalists while reporting from a conflict zone.

The book unveils the trials, travails and triumphs of a ‘combat’ journalist who was fortunate enough not to be reduced to a statistic in the long list of journalists killed, injured or maimed while reporting from the region.

It is also a story of how I internalised many of the traumas I had to witness, and how I had to seek professional help for psychological trauma.

Nobody talks about the psychological trauma faced by a journalist. The book can also be called a survival guide for journalists in a conflict zone. I hope it will serve as a document for media students and researchers working on conflict journalism.

You have covered all the northeastern states for some of the leading publications in the country for over two decades. Do you believe that being a woman in this job was even more difficult during the 1990s?

I have always believed that you can either be a good journalist or a bad journalist. But in many ways, one’s gender comes into play. We had to juggle our way through without really caring for our own safety and security. I don’t think things have changed much for a woman in the field.

There is not much of a support system for women journalists, especially those covering under reported regions, smaller towns and villages. This includes access to the internet, mobility at odd hours and safety among others. Apart from that the legal, social and even psychological support system is lacking.

It’s time we come out and share our experiences, and if possible, create a safety net for female journalists reporting from a difficult terrain. I don’t think much has been spoken or written about this issue.

‘The northeast’ always grabbed the headlines for issues like insurgency and conflicts in the last three decades, though it has changed a bit now?

Northeast India, which is often ghettoised as a monolith, is a paradise for journalists. There are so many untold stories of men, women and children waiting to be told. It’s true that it is often in the news for the wrong reasons. But that did not deter me from chronicling the lives of the people of the region.

After quitting Tehelka, I thought I would continue writing in the so-called national dailies. However, when I had to struggle for space for my stories, I decided not to beg for space but to create my own. I had realised the might of the internet, and launched my webzine The Thumb Print.

And within a few years, we have been able to storm our way into cyberspace.

Your book also narrates some incidents of human rights violations. What was your experience reporting those incidents?

Reporting conflict has a fear factor that is real. I would be lying if I said I was not scared at times. In the book I have also written about my vulnerabilities and apprehensions. But it took a lot of courage to speak out.

I would urge journalists to think about their personal safety and security as a priority. The story is important but so is your life, and your mental and physical health.

Your first book, Mothers of Manipur deals with a very unusual subject. Probably the first time in India that such an incident happened. Can you tell us about your experience meeting those brave women?

I met these women as part of my routine reporting assignments. They welcomed me to their homes, inspired me and showered me with love and affection like any grandmother would do. I felt that it was important to tell and document their stories, whether you agree with them or not.

On July 15, 2004 in Imphal an unusual scene unfolded in front of the Kangla Fort, the headquarters of the Assam Rifles, a unit of the Indian army. Soldiers and officers watched aghast as 12 women, all in their 60s and 70s, position themselves in front of the gates and then, one by one, strip themselves naked.

The imas, the mothers of Manipur, are in cold fury, protesting the custodial rape and murder, by the army, of Thangjam Manorama, a 32-year-old woman suspected of being a militant.