A Blot on Chennai’s Colourful Art District

‘Sensitise the men and tell them about the legal action that can be taken’

CHENNAI: Kannagi Nagar, a resettlement colony where around one lakh people live, is also Chennai’s first art district. Its walls sport bright murals. Behind them, most men here perpetrate violence on their partners. These women rarely take recourse to the law.

*Reena, 45, has suffered violence for the last seven years of her marriage. Married when she was 19, her husband, an auto-rickshaw driver, routinely comes home drunk after work, uses violent language, hits her, and next morning acts like nothing happened. She retaliates by shouting and screaming at him, but nothing changes.

Reena takes care of her two children, a son and daughter, and runs the household with the earnings from her housekeeping job, barely enough for the family of four. Her husband uses the money he earns to buy alcohol.

“He comes home and tells me whatever he earned was spent on petrol. But looking at his drunken state I know what the money actually bought,” she says.

She says alcoholism is the foremost reason for the violence perpetrated on her all these years.

A recent study by the Voluntary Health Services found widespread violence against women and children in Kannagi Nagar. The research institute’s director Dr Vijayaraman was quoted as saying that here, “62% of women have faced sexual violence, 53% are forced into child marriage, 71% experience child abuse and 79% face sexual harassment.”

According to *Seema, 28, some 90 percent of the families in Kannagi Nagar have domestic violence issues. Going to a relative’s place is the most common option for the woman, she explains. After a short period the husband “convinces” her to return, promising good behaviour. “And the woman is back with her husband.”

She is holding her son who cannot understand what the conversation is about. “I have been through this situation. I went to my parents’ house and came back later, after my husband and I had resolved our fight.”

Do women ever approach the police? “They do.” But the same drill unfolds, of going away, returning to the husband’s house, asking the police not to file a case. “So nothing serious ever gets done about these cases.”

This is confirmed by senior inspector R.Hariharan at the Kannagi Nagar police station.

“In a month, women come here 28 days to complain about domestic violence. Soon they come back and withdraw the complaints. This is the pattern. So there are no official complaints lodged.”

Women sometimes go to their native place, but return after resolving the issue with their husbands.

Hariharan says that women approach the police to “threaten” their husbands and sort out the issue. “They do not ask us to file cases as they do not want to pressure their husbands.”

“Registering a complaint is futile,” he adds.

How do the police respond to such complaints? “We make a call to the husbands.”

It is not easy to have women talk about domestic violence. Area resident Vasanthi, 51, says she knows many women who are victims but “they never speak about it.” She echoes the police claim that the couples eventually reconcile, and confirms the sequence of events.

S. Shakthi, of the Prajnya Trust which works in the areas of education and gender equality, says there’s no single reason women do not report domestic violence. “Women have different reasons,” she says, including family honour, a reluctance to oppose family values, traditional gender roles, financial dependence, and fear.

Many do not talk openly about domestic violence because of fear. “There is always a risk of more violence as the victims continue to stay with their abusive husbands… Some women feel they have nowhere else to go, so they endure the abusive relationship.”

Kannagi Nagar resident Rekha, 28, thinks that women’s attitudes also contribute to their continuous abuse. “If we question a man beating or ill-treating his wife, the victim herself says it’s none of our business.”

She says that women generally do not talk about it from embarrassment.

“It happens in every house here. It's very normal and very usual. The women don't care,” she smiles.

A negative approach and obstruction by the police are also to blame, says M. Shiamala Baby, founder director of Forward, the Forum for Women’s Rights and Development.

“I remember how a woman was treated in a police station. The policewoman said ‘go and bring the man here and we will take action.’ How can we expect women to come forward with complaints in such an environment?”

Kannagi Nagar, she says, is a “hub of crimes.” Substance abuse, sexual abuse and rights violations are “widely prevalent” here.

Baby, herself a domestic violence survivor and an active advocate of women’s rights, says a “shaky family structure” and alcoholism are the major factors behind the rise in domestic violence.

“Money is the reason behind most of the quarrels,” says area resident Geeta, 37. The expression on her face changes as she recalls the troubled times during the lockdown last year. The men, primary breadwinners in most households, lost their jobs. This became a major reason for the fights that erupted.

The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act of 2005 provides for medical resources, accommodation in shelter homes, monetary relief, counselling and legal aid for survivors. But “seldom do women know how to get help under the act,” says Baby.

Shakthi agrees. “In general, across all sections of society, I think there isn’t much awareness on the Act… The government, through the Tamil Nadu social welfare department, is trying to raise awareness, but I’m not sure how effective it is… The facilities exist but is the government promoting it effectively? To me, that is the first step. Then comes raising awareness on the legal rights.”

She thinks it’s important to let women know they have a place to go in case of an emergency. She gives the example of the public One Stop Crisis Centres, which serve as shelter homes for emergency and non-emergency access, and where legal and medical aid and other help is extended to survivors of sexual violence. These have been publicised through flyers in public transport.

As for non-profit organisations working to familiarise women with rights and redressal, she says funding has always been a serious issue.

Baby thinks that rigorous awareness building is the need of the hour, as women “seem to know everything other than the law that protects them.” She recalls an instance when a “very highly educated” victim of domestic violence didn’t know the provisions of the PWDVA.

Unlike most women interviewed, who said that domestic violence is widespread here, Kannagi Nagar resident Kasiammal, 51, dismisses the claims. “Nothing of that sort happens here.”

And senior inspector Hariharan says women here do not even know what domestic violence is, so expecting them to know about the PWDVA is far fetched.

No divorce takes place due to domestic violence in Kannagi Nagar, he points out. “The women here are too dependent and tied to the traditional gender constructs. They hardly step out of their homes, let alone see divorce as a solution.”

To curb the violence of these men, Shakthi thinks “we need to hold our elected representatives more accountable.” There should be a demand for gender issues to be included prominently in party manifestos. “I think as voters, we need to tell them that they have to take gender concerns seriously.”

The police, of course, need to be “more sensitised… Whether it’s the police, or the doctors who are often the first point of contact in such cases… everyone in the chain needs training.”

Baby goes a step further. “Sensitise the men and tell them about the legal action that can be taken if they unleash violence against their womenfolk.”

*Names changed

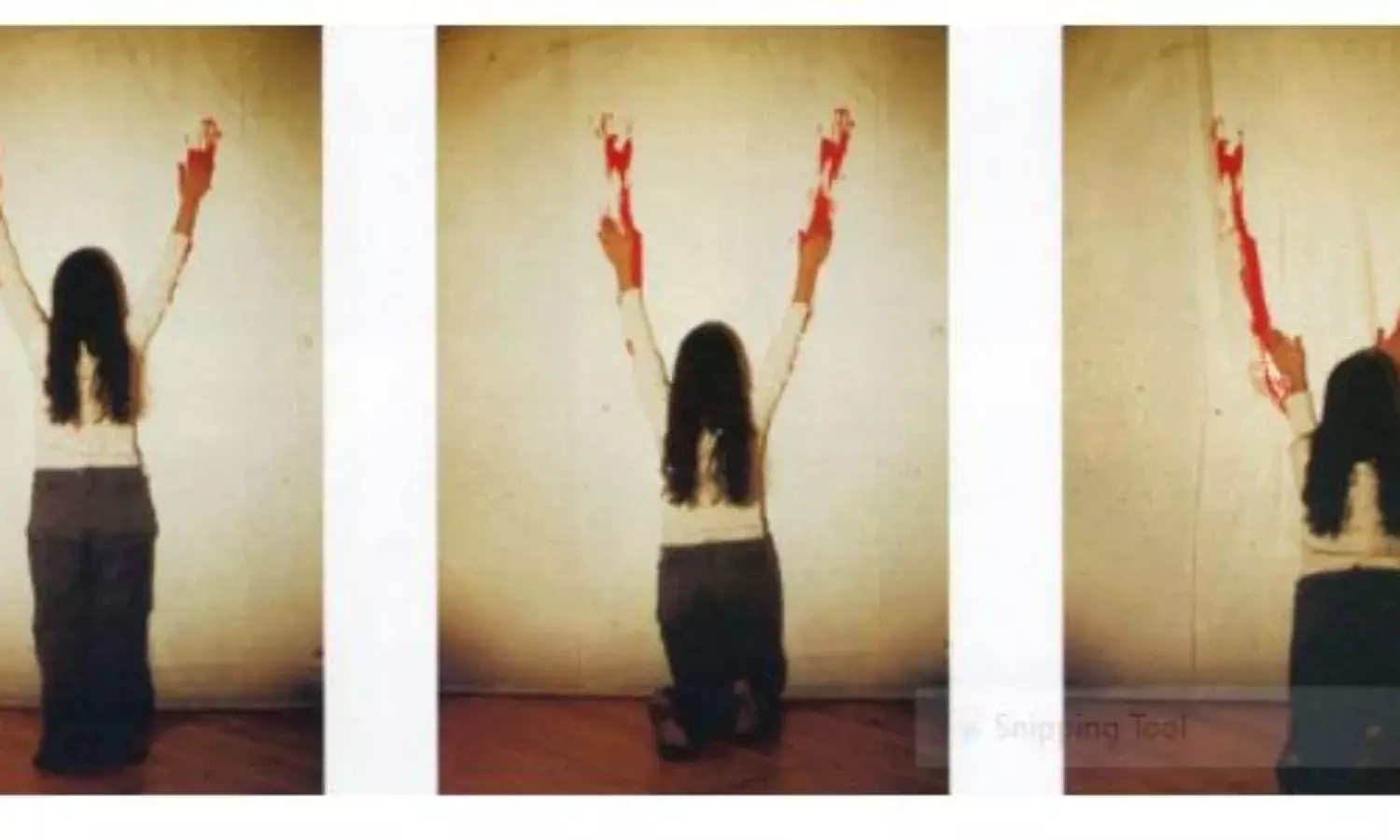

Images: Ana Mendieta