The Maharani who Founded the BJP

My friend, the Rajmata of Gwalior

I met the Maharani of Gwalior, Vijaya Raje Scindia in 1946, in Gwalior. My father was the Dewan of Gwalior called the Vice-President of the Council. We shifted from Bangalore where he had been a cabinet minister in 1946. I was 13 years old.

A feature we didn’t know was that the women of the palace, the royalty, were in a kind of ‘purdah’. Thus, the first time I set my eyes on Maharani Vijaya Raje Scindia, she was in a reception for women hosted by her in what could be called the palace zenana. It was a beautiful huge garden and tables and chairs were spread across the lawn. I recall a galaxy of elegantly dressed women with fine chiffon or chanderi translucent sarees covering their heads, seated at tables for five.

The Maharani herself was a stunning beauty, with a tilak made of the Gwalior insignia, a cobra, decorating her forehead. She also had her head covered with the pallu of her saree.

The Maharani, with a warm smile on her face, walked between the tables, greeting her guests and creating laughter. Being the wife of the Dewan, my mother was one of the people she came to greet and welcome. She welcomed my mother in perfect stylish English, “Namaste, Mrs Sreenivasan, hope you are comfortable.” My mother, also being a graceful beautiful woman, stood up and made a deep bow and namaste to this young queen and said, “Very happy, and you must come to our house” and introduced us, two of her daughters aged 12 and 8, who were with her.

There were many other times that my mother would go to the palace for “ladies only” cultural events, or for just getting together. It was hard on my mother as she was completely blank in Hindi, but again the Maharani put her at ease as she spoke impeccable English, and was particularly loving to my mother, who herself had a charisma which climbed over language and cultural barriers.

The Maharani had diverse interests, many skills and was active. She organised many events including one that I got close to, a dance drama called Skandagupta.

She had chosen her actors and the rehearsals would take place on a stage within the residential part. At the age of 12, I was somewhat uninhibited and would mingle easily with the adult women who were always around the Maharani.

So on one of those occasions, she asked my mother if she could have me join her as one of the actors, in the new dance drama she was putting up. It was part of the scenario to have women carrying beautiful baskets of flowers on their heads and walking gracefully across the ‘street’, as a kind of backdrop to the main drama taking place in the front of the stage. She recruited me for that and I was thrilled.

So every day, the coach-and-four would be sent to our house and I would go off to the palace.

One afternoon, it was a dress rehearsal as I remember for it was both a shock and a joy for me. I was shocked because I had to undress, put on a lehenga, choli and a chunni. I had never undressed in front of anyone. The older women laughed and made a fuss over me and quickly had me agreeing. But the most outstanding part of the dressing-up was their surprise at seeing the length of my plait.

We girls from the south, as is well known, are not allowed to cut our hair. I had a long black plait at least two feet long, coming right down below my bottom. My hair was thick and curly and the plait therefore, became thick. This drew so much attention that many of the women would come and touch it, to see if it was real or some artificial extra. Since this was all very new to me, I cried.

However, after the first dress rehearsal, I became more adjusted and thoroughly enjoyed the palace visits, the rehearsals, and listening to the speeches as well as the music. When we finally presented the play I was carrying a large flat basket of flowers on my head and swishing across the stage and loving it. Of course the best part was the way the Maharani would pamper me, come and talk to me, put her arm around me and encourage me.

My father was Convener of the State’s reorganisation committee set up to bring the autonomous kingdoms into the new Republic of India, and so he was very often out in Delhi. My mother kept herself busy attending the ladies functions. We, the daughters, had no schooling for that year as all the schools taught in Hindi.

My father tried to compensate by introducing me to the famous Mr Pearce, principal of the boys’ residential school called the Scindia School. But again with a very strong “purdah system” I could not enter the school.

So we had this almost comical situation where Mr Pearce would walk down to the car in which I had been brought to school. He would sit with me in the car for an hour, teaching me, to help me pass the secondary school exam. While he was a lovely man and tried his best, it was an impossible situation, so we gave up.

Gwalior ceased to be a princely state and joined the Republic in 1947. We moved out of Gwalior at the end of 1947 and returned to Bangalore, where I rejoined my high school for the last year. Thereafter we completely lost touch with the royal family of Gwalior.

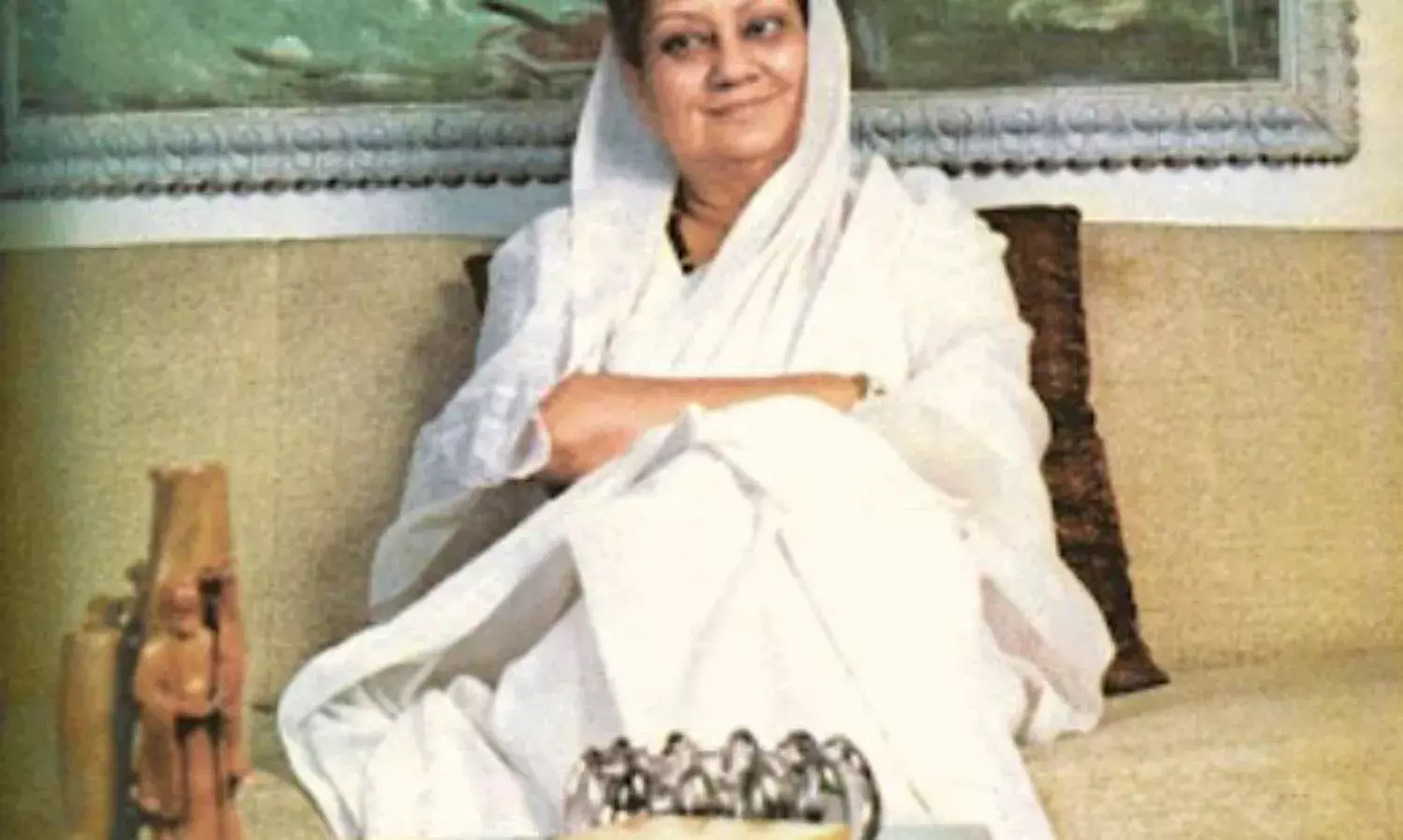

However, decades later, one time when I was flying from Bombay to Delhi, I noticed my friend the Maharani, now transformed into a white-clad, head-covered, unadorned woman sitting in a seat three rows behind. Naturally, she saw me looking at her, and with a flash of recognition called out to me, “Devaki, come and sit here.”

The rest of the journey we just chatted away and caught up with each other with promises that we must meet. Thus began our reunion.

Then the incredible took place. In 1969, by which time I was married and had children and was working, we moved to a house in Civil Lines, thanks to the generosity of Sheila Dhar. While in Civil Lines, I was also pulling together a book on the status of women in India, for the government of India. The book was to be presented at the first UN World Conference on Women held in Mexico, in 1975.

Civil Lines also housed the Delhi residence of the Gwalior Royalty called the Gwalior House. I contacted her and then went across for tea time and conversation. I had collected essays from various spaces such as historians, politicians, demographers, activists and so on, each addressing what is called the ‘status of women’ from their perspective.

I requested her to contribute an essay which would be from the perspective of a maharani, revealing the diverse roles of women in India. She readily agreed and a few weeks later sent me a brilliant essay, each page signed by her to show its authenticity. In those days we didn’t have fax machines or computers, so her original was with me and we were copying it, as part of the collection of essays that went into the book.

I was thrilled by the diversity of the authors that I had: Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, Lakshmi Menon, Veena Das, Romila Thapar and so on. And there would be also Vijaya Raje Scindia, as the former Maharani of Gwalior. The book was to be released by Dr Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed, then President of India in 1975.

But no! All of a sudden her closest aide who was with her when I used to meet her in Civil Lines, Nanaji Deshmukh came to our house and asked me to return the Rajmata's papers immediately – and said, “I hope you have not used it yet.” In retrospect, I regret that I didn’t have a copy, only the original. He was so fierce, adding she should not have given it to me, that I returned the article to him.

They buried it! What a loss! Imagine the story written by a Nepali princess who not only became the Maharani of one of the largest north Indian states, activating the Zenana, the secluded women of the region, but then founding, leading the most powerful national party, alternative to the Congress! A party, the BJP, which is now the leading political party.

What a person and what a story it would be, if only it was not snatched away from me by Nanaji Deshmukh. But I lost her story and would never forgive myself for not getting it copied. I had not even read it because I had so many manuscripts in the house and hers was taken away within two days of her giving it to me.

Nanaji Deshmukh later initiated a remarkable rural development centre in Chitrakoot. Ironical as it may appear, when my husband was member of Planning Commission and was looking for innovative initiatives which succeeded in self-reliant rural transformation he met Nanaji, he bonded with him and in 1990, was able to provide to Chitrakoot the maximum that the Planning Commission grants to any NGO.

My husband, Lakshmi Jain must have visited Chitrakoot at least 4 times and he and Nanaji would exult on how simple initiatives can be transformatory. But alas! I only had the painful memory of the loss of the remarkable story of a Nepali princess educated in English, one of the founders and leaders of a national political party which is now controlling India.

However, we did not let go of our bonds. Maharani Vijaya Raje Scindia visited me in the apartment to which we moved in Jor Bagh. She was accompanied by Madhavrao Scindia who was just about to join politics. My husband was with me and in our presence she told Madhav, “You should meet Devaki and Lakshmi, you should learn about India from them and take their advice as you go along in the government.”

Madhav was very polite and said, “Yes, please be in touch”. But as it happened, quite understandably, as he moved up in the political power hierarchy becoming a Member of Parliament and later a Minister, even though our paths crossed at many public events, we could not do much together. However, he was always respectful and caring.

Looking back, it still astonishes me how this young queen morphed herself into an amazing, powerful leader of a highly conservative “desi” male-led political party. A Metamorphosis! Essays about women political leaders in south Asia have mostly been derogatory, they are characterised as dictatorial, impetuous and most of all ridiculed for coming into power as widows, the shadow of their male partners.

Vijaya Raje Scindia was different. She led, she built, she strategised and she won – the founding mother of the BJP.

Devaki Jain, economist and writer, is currently honorary fellow of St Anne’s College, Oxford

Assisted by Kritika Goel, MPhil, Ambedkar University