Why Do Women Remain At the End of the Stick 75 Years After Independence?

Kadambari Devi and Rabindranath Tagore

“But where is the sweetheart of mine who was almost the only companion of my boyhood, and with whom I spent my idle days of youth exploring the mysteries of dreamland? She, my Queen, has died and my world has shut against the door of its inner apartment of beauty which gives on the real taste of freedom.”

These poignant words of lament were those of the esteemed poet and musician Rabindranath Tagore from a letter he wrote to a fellow social reformer, CF Andrews. In the letter the poet bemoans the death of his muse, his friend, confidante and critic, his sister-in-law, Kadambari Devi. Not many are aware of her or her influence on the great poet’s literary career or of how she continued to influence it even after her untimely and tragic death.

A figure shrouded in mystery, search her name on the internet and a couple of faded photographs pop up. These pictures and the literature her beloved brother-in-law dedicated to her are all that remain to remind the world that she existed.

Kadambari Devi was born to a middle class family. Her father, an accountant, worked for the Tagores. At the age of nine she was married off to Jyotirindranath Tagore, elder brother of Rabindranath. This seeming ascension in status, however, did not work out well for her. For, in that huge Tagore ‘thakurbari’, Kadambari was a misfit. Shunned by the senior Tagore women for being ‘low of birth’ and too young to provide her ten years older husband with any sort of companionship, Kadambari was lonely.

Being a modern thinker, Jyotirindranath believed in the emancipation of women. He therefore ensured the education of his illiterate child bride. Kadambari was educated in literature and mathematics. She was given responsibilities too. Kadambari was assigned Rabindranath’s care. Being his elder brother’s wife, his ‘Bouthan’, her status was supposed to be akin to that of a mother for him. The fact that she was a mere two years older to him didn’t really matter. She was to look after his needs like a mother would, and take care she did.

As Rabindranath Tagore later recounted in his long essay, ‘Chelebela’ (boyhood), “My new sister-in-law could cook well and enjoyed feeding people. As soon as I came from school, some delicacy made with her own hands stood ready for me. One day she gave me shrimp curry with yesterday’s soaked rice, and a dash of chillies for flavouring, and I felt that I had nothing left to wish for…”

Although his guardian in name and duties, Kadambari was still a young, lonely child and he was the neglected thirteenth and the youngest child of his parents. They naturally found companionship in one another and friendship blossomed between the two. She became his playmate and confidant. Together they would sit in the roofed terrace garden that she would tend and have prolonged conversations. Their imaginative young minds found camaraderie in one another, and it was there in that little garden that Rabindranath’s literary career began.

Having been previously deemed an academic failure by his teachers and a good-for-nothing by his family, Rabindranath discovered his literary talents during his course of discussions with Kadambari. His imaginative mind and his way with words found an attentive audience and a merciless critic in her. To her he would read his poems and she would offer him her critique, always spurring him on to being better. Her sharp wit and sound counsel led to him playfully nicknaming her Hecate after the Greek goddess of the moon, witchcraft and magic. She on the other hand, lovingly called him Shubho, after the sun.

Her husband Jyotirindranath supported this friendship of theirs and all was tranquil for a few years. Rabindranath’s literary career soon took off while Kadambari grew up to be an impressive young woman who would go horseback riding (horrifying the people of Bengali society) and conduct literary events at the Thakurbari in Jorasanko.

However on the personal front, things started deteriorating fast for Kadambari. Deemed old enough to bear a child, yet unable to conceive, Kadambari endured mockery and jibes from the other women in the family who declared her barren. Her husband, Jyotirindranath didn’t provide any comfort either. He remained perpetually busy, dealing with matters of business or attending literary meetings in which he refused to involve her. The breaking point came probably when Kadambari discovered a love letter in one of his pockets. It was from an actress in one of the theatres her husband frequented. One can only assume the effect this discovery had on her.

Maybe to allay her loneliness and to achieve the filial affection she so craved, Kadambari Devi adopted a young girl Urmila. Urmila was the daughter of Kadambari’s sister-in-law Shorno Kumari. This happiness nevertheless did not last long and the nadir of Kadambari’s existence came on quickly. Urmila slipped and fell down the stairs and died in Kadambari’s arms.

After this Kadambari’s downward spiral began. During this time, twenty-two year old Rabindranath’s marriage came to be fixed with nine year old Mrinalini Devi. Like a dutiful son he went through with it and four months after his marriage, Kadambari Devi committed suicide by overdosing on opium.

We will never know what precipitated this tragic end to her mere twenty five years of life. Was it passionate grief over losing her beloved companion and sole friend to marriage to another? Popular culture certainly leans towards that theory, often depicting her and Rabindranath’s relationship as a romantic one. Or was it the depression and loneliness brought about by the personal loss, archaic customs, expectations and misogynism that ate away at her? Again, we wouldn’t know.

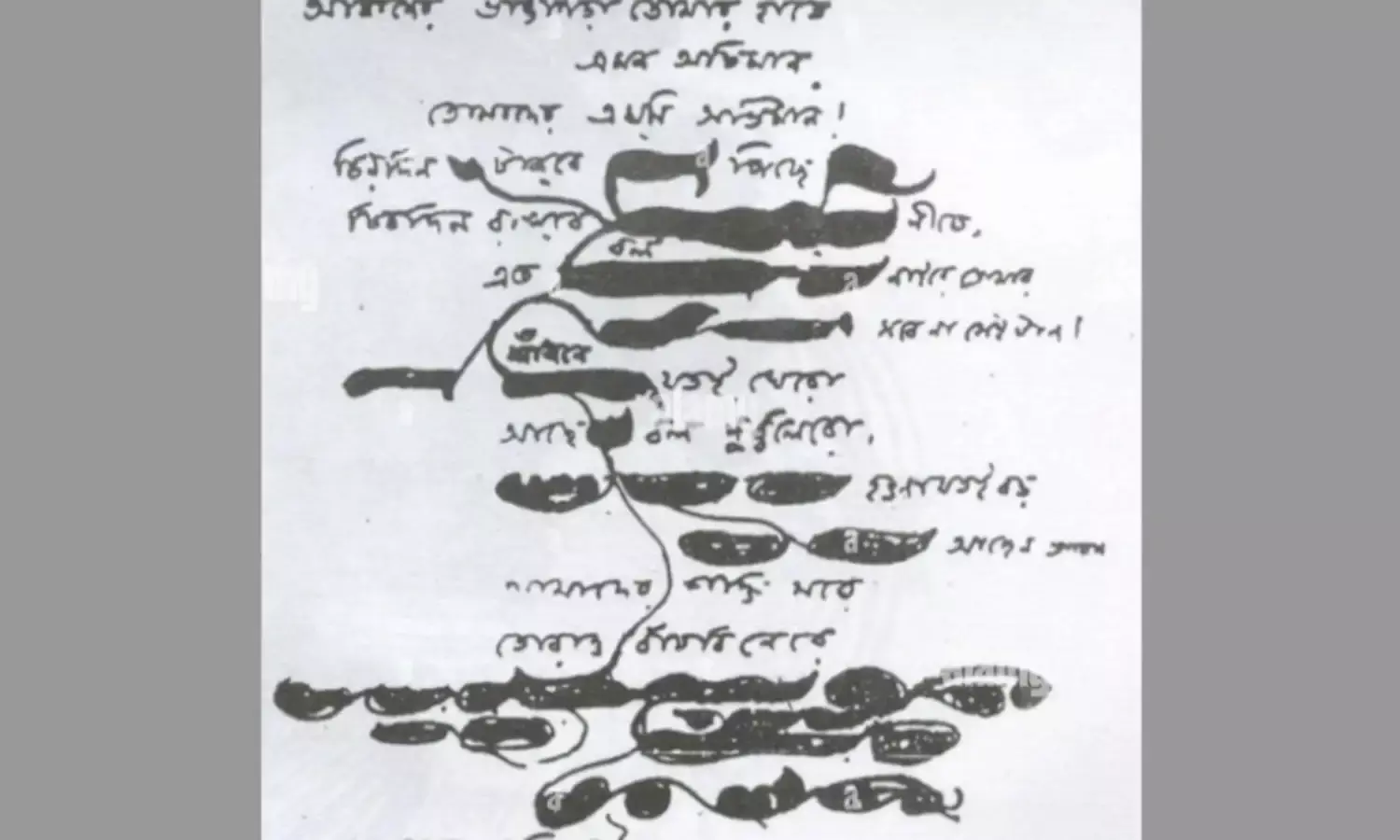

Rabindranath Tagore was much affected by his sister-in-law’s death. So much so that till his last breath he kept referring to her in his literary works. He wrote the now popular song ‘Tobu Mone Rekho’ (Pray remember me), in her memory. His song, ‘Amaar praner pore chole gelo ke’ (The one who went out of my life) too was written for her. Its lyrics, poignant and longing, yield the void his muse left in his life with her untimely death.