Gender on the School Walls: People of India, Bad Manners and Ideal Boy Charts

The world of possibilities has started acknowledging different genders, but is still lacking in accepting differences within them. Without anyone or any one, as its definition, genders exist as plurals but are practised as singular. Baby steps to education, are the very steps towards gender education.

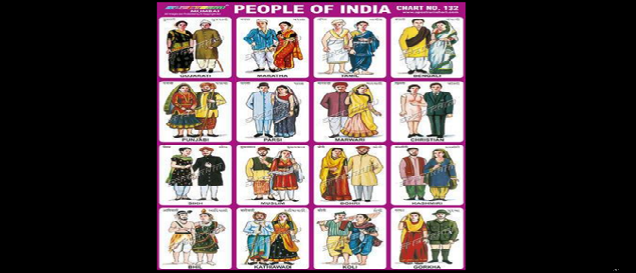

Inked in stereotypes, the charts that wall the schools, nurture young minds, as well as the expected gender roles. Exposure to such charts round the clock ingrains ideas. Unquestioned, these ideas of what it means “to be a man/woman” transgress into lifelong ideals. Ideals that the grown eyes long are drawn from those hopscotch days of childhood. Charts like “People of India,” that flaunt the country’s diversity, fail to draw similar pictures of gender. Different in attire, but similar in their body types, the diversity is silenced.

Diversified in clothes, men in the chart stand tall, and unified for unreal reasons. Women in inches, fall short among the men, denied height higher than them. Target of taunt and tease are genders that defy ‘height rules.’ Where ‘too short’ is the spell that haunts the boy’s world, ‘too tall’ is the evil charm for the girls. Kamala Bhasin while throwing limelight on where these teaching tools lead to raised questions familiar yet hushed, “How many women would agree to marry a man who is shorter, younger and earns less than her?”

While slender and sleek images of women across states, appear on “People of India,” men with lean bodies remain invisible. Lessons on manhood that begin in classes continue to breathe in glossy magazines and flickering screens. Beginning the tutorials of femininity in schools, the charts become the trailer for their movie of gendered life. Nature which hasn’t moulded any two alike, Ms Bhasin remarks dwindle down the 3 billion men and women alike. Painted in light tone hues, the charts negate the reality of darker shades. “Homogenisation of everything”, from clothes to preferred north Indian complexion, Ms Bhasin comments on the absurdity, charts promote.

Trimmed hair that crowns caricatures of men in the charts, answers why the men with longer strands still prick the native vision. Luscious and long, strands free or rolled adorn the women while writing the history of short hair stigma. Femininity that shares its definition with long hair in India, is seen lost with the lost hair. Once the locks are left loose to grow, question of hair, becomes a question of masculinity. Rahul Roy who debates over the “set of rules” which are culturally acceptable .i.e gender, shows the role of the behaviour charts in creating them.

Bad Manners' promotes the very ‘Boys don’t cry and girls don’t fight’ generalisations. Shared memories of broken toys and sibling quarrels, gets tainted with prejudice in ‘Bad Manners.’ Hurled hands and teary eyes that the sister with her broken toys expresses, is an emotion denied to her brother. Boys surface as ones irritating and never as ones irritated, among sibling rift. Lesson of being male, that draw on factor of violence, sketches the women at the receiving end. Reality shrinks to one dimensional, with charts promoting gender roles. Not appearing as often as males, female caricatures lack visibility in print and reality.

“Schools and books have the authority to tell the truth,” as Ms Kamala Bhasin concludes. Virtual stores like Indiamart and Spectrum that market such charts, prove its expanding influence. With education as a right, and the introduction of compulsory English from 1st standard in UP government schools, the tools of chart call for careful revisiting.