Congress Concedes Partition, Again

The public figure 'Rahul Gandhi' is renewing its father's mistakes

For at least a year now the Congress party president and his mother have been insisting to the public that theirs is not a ‘Muslim party’.

‘People think we are a Muslim party, I don’t know why,’ simpers one. Devotees of the other insist he wears a ‘sacred thread’ - where can I get one? - and so, to the advantage of the governing BJP, for want of a better word, the election issue becomes, Hinduism versus Hindutva.

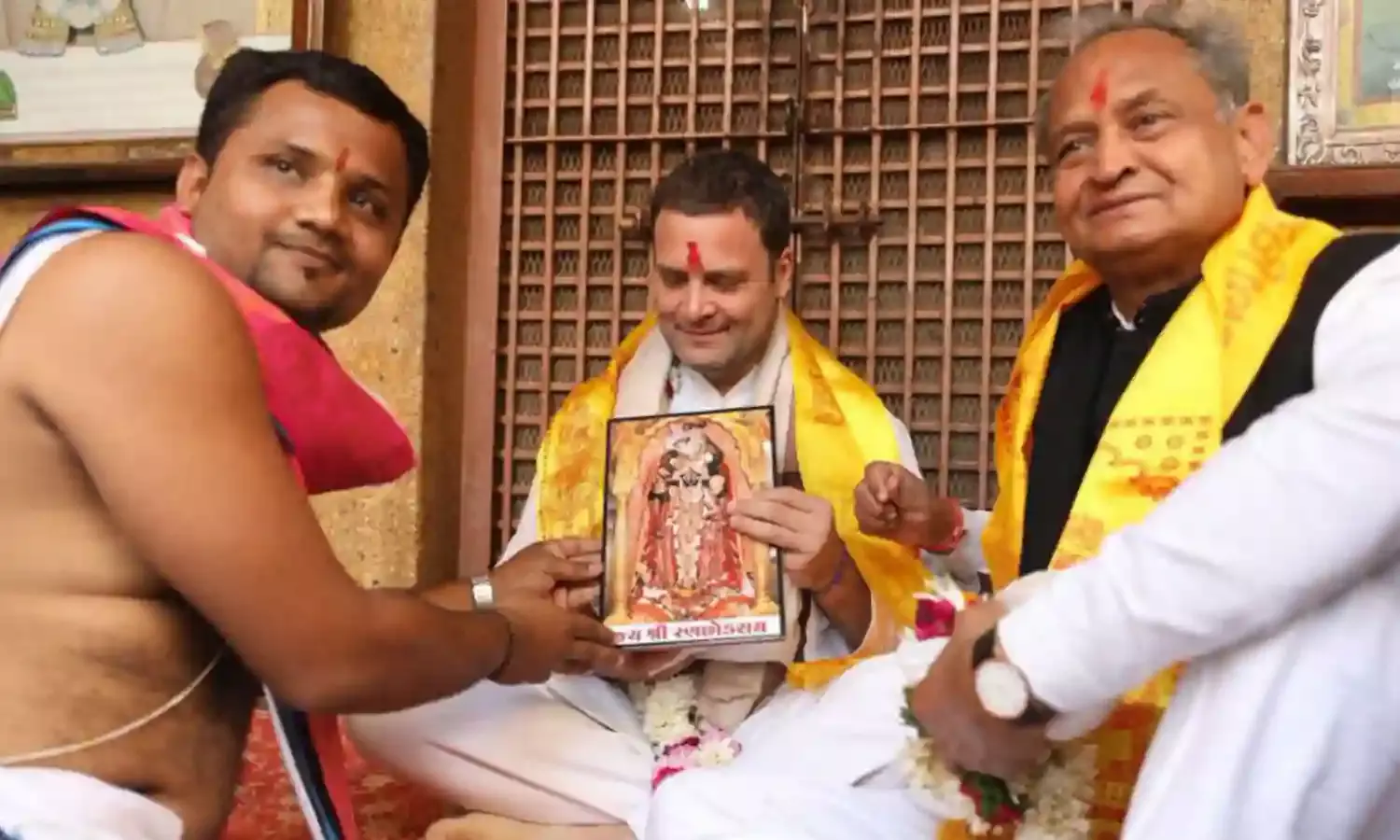

In furtherance of this irrelevant debate, the Congress president extended his temple run during the campaign for the recent assembly elections, to include a number of mandirs in the nominally Hindi speaking states. In its manifestos in MP and Rajasthan his party promised much for cows, and their cruel commercial use.

As the Congress tries to shed its allegedly pro Muslim image - and what did it do to earn this reputation anyway? - its temple, cowshed, urine production moves should not be seen in the light of complacent electoral calculations alone.

Nehru’s party has conceded a crucial point to the BJP and other fundamentalists: that no one can stand for Muslims and Hindus equally.

Religious minorities have no place in the Hinduism/ Hindutva contest. Women and outcastes are subservient in it.

By accepting these terms the Congress has agreed to partition the polity, and is playing a dangerous game.

![]() By refusing to represent Muslims, it forecloses the option of politically undoing the caste-class hierarchy.

By refusing to represent Muslims, it forecloses the option of politically undoing the caste-class hierarchy.

It agrees to lie that Islam and Hinduism are monolithic and distinct - or at most a benign Kumbh Mela, Hajj pilgrimage, salad bowl affair.

Who does it hope to convince by sending its president and putative prime ministerial nominee to assorted temples and trusts?

Voters swayed by such posturing will expect the state to be similarly run.

Such a government will only abdicate its constitutional responsibility to govern a secular republic. It will be unable to see minorities of caste, class, religion or gender as anything but the perhaps worthy recipients of charity from above.

Meanwhile its detractors will go on calling it pro Muslim - as long as that remains an accusation - and its disproofs will turn even more violent than before.

In the Modi years, minority run educational institutions have been besieged - being about the only counter to bigotry and redistributive measure accorded religious minorities in the Constitution. The Hindu fundamentalist central government, charged with setting these up and letting them run, has instead brazenly argued for their non-minority character in the courts.

The question of party ideology grows bigger, with the subordination of state institutions to the government of the day - its effects most recently visible in S.R.Sen’s judgment from the Meghalaya High Court. In it Justice Sen appears unhappy with the Constitution, and won’t say why.

The windsock intellectuals’ nonresponse to Hindutva’s terrifying claims upon our bodies and minds - ‘But Najeeb took an auto to Jamia’ - is likewise marked by dogfaced calculation.

For consumers the cow only symbolises the Brahmin. As the Brahminical Left prepares to take the reins from the Brahminical Right, and the Baniya-etcetera corporates once more switch parties, as schoolbooks preach poison and still the seas rise - all the rest of India falls truly between the cracks. As intended.

We stand stopped and unprotected.

The Congress isn’t immediately responsible for the way these fissures gape in Modi’s Hindu Rashtra. But like Indira Gandhi in Khalistan, Rajiv Gandhi in Tamil Eelam or Narasimha Rao in Ayodhya, it is foolishly trying to profit from it.

The public figure ‘Rahul Gandhi’ is renewing its father’s mistakes.

In his Autobiography Nehru describes an article he wrote, ‘on Hindu and Muslim communalism, showing how in neither case was it even bona fide communalism, but was political and social reaction hiding behind the communal mask.’

‘I did not imagine, of course, that I could conjure away the passions that underlay the communal spirit. My object was to point out that communal leaders were allied to the most reactionary elements in India and England, and were in reality opposed to political, and even more so to social advance. All their demands had no relation whatever to the masses. They were meant only to bring advancement to the small groups at the top.’

‘The oft-repeated appeal for Hindu-Muslim unity, useful as it no doubt is, seemed to me singularly inane, unless some effort was made to understand the causes of the disunity.’

The empire run by a rich global few may be a major cause of this apparent disunity, in Nehru’s time and in our own.