Re-Defining The Significance Of National Icons

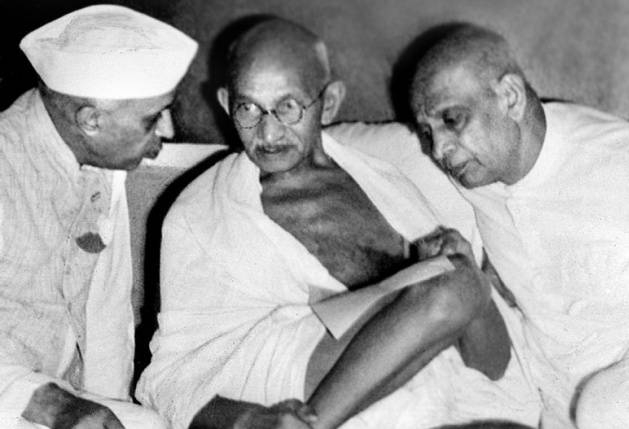

Palel, Gandhi and Nehru

The invocation of national icons in politics has always formed an integral part of intersections between politics, culture and history. The central contours of India’s freedom struggle too were marked by discourses and foundations that drew sustenance from symbolisms drawn from various cultural and historical narratives. Since culture and history are an indispensable component of nationhood and appeal to the collective consciousness of the mobilized people, their infusion to contemporary discourses and ideas in politics and policy lends acceptance, efficacy and legitimacy to current political ideas. Such interactions between contemporary politics and symbolic history-culture constitute a process through which history is not only brought to bear upon the present but is also itself re-written and appropriated for the fulfillment of current discourses. It also constitutes a process by which ‘national’ history is sought to be defined and contemporary socio-cultural identities shaped.

However, there is a very thin line between the invocation of symbolisms and leaders of the past to reinvigorate the political discourses of the present and an appropriation of the past to entirely re-define the past, present and, most importantly, the future. In the current Indian political context, it is the latter process which is occurring, and is marked by the involvement of the major national political parties as well as of the state. The redefinition of the institutions of the public education system as well as the consistent appropriation of national political icons from India’s recent political history – Nehru, Sardar Patel, Gandhi and Subhash Chandra Bose – by India’s major political parties, the Congress and the BJP, is beginning to form the cornerstone of an emerging discourse which is likely to be characterized by the dominant historical narrative out of the various competing interpretations of history. The relevance of such a discourse lies not only in its power to redefine Indian history, but is more crucial in legitimizing the broad directions that debates in Indian politics will take in the future.

The appropriation of history in the current context, as evident from the invocation of leaders from India’s recent political history, is, thus, less of a cultural or identity-based struggle to redefine history, and more of a struggle to determine the kind of voices and ideas that will have relevance in India’s political future. This is evident, both, from the content of mobilization narratives around national leaders and from the factors that have motivated the major parties to engage in this process.

Re-invocation of Congress’ ideological basis:

The recent gathering convened by the Congress party on Jawaharlal Nehru’s 125th birth anniversary has been interpreted as sending out a clear political signal for consolidating the unity of the party. Convened under the umbrella of ‘secularism’, the conference formed a critical first step towards the potential reinvigoration of the party in times of changing national politics. With the BJP victory at the centre inaugurating an era of ‘saffronization’ in various national institutions and the RSS consistently working towards strengthening the already strong organization of the party at the grassroots, the Congress comes across as a decaying and receding force in Indian politics. Not only have the recent months seen renewed internal dissent within the Congress with various state leaders questioning the central leadership, but the party also faces the external challenges arising from the BJP’s political offensive along the two lines of social and political dominance of the saffron ideology and of the weakening of the Congress’s mass organizational base as is evident from the general elections and the state by-polls. Thus, the factor of preserving political relevance has become of prime importance for the Congress. Only so will it be able to retain its distinctive foundation in the impending political future without being accommodated or marginalized by the new forces that have begun to determine the Indian political context. Invocation of Congress icons like Nehru form a part of this kind of a process. It will lend legitimacy and cultural foundation to the eroding ideological base of the party.

At the same time, what Congress is doing by invoking national icons is not an active appropriation of history. It is simply, at present, a struggle to remain relevant and re-visit the appeal of ideals of secularism and democracy that have been the cornerstone of the party. Even the debate over Sardar Patel and the question of his divergence from the RSS ideology is a part of this struggle. While the Congress has clear pragmatic political aims and strategy in mind, it has not launched an active offensive to re-define history by changing the very nature of the context of these national icons. Rather, its appropriation of these national heroes is occurring within the context of re-invigorating its own ideology and relevance and forming a pragmatic political unity to counter the BJP. The context is, thus, ideational rather than historical.

At the same, however, this struggle to retain relevance is also tending towards embracing polarizing positions on the part of the Congress. In order to ensure that its main political rival, the BJP, does not enfold mainstream political icons of the Congress, such as Nehru, Gandhi and Patel, within its rhetoric, the Congress is having to validate its position by going to the very extreme and declaring that the BJP cannot appropriate these leaders, since they were ‘Congress’ leaders historically. In a statement to a leading national daily, professors from the disciplines of Politics and History attest to this tendency within the Congress. They argue that not only has the Congress of the present times abandoned the ‘middle’ ground for which it was always known as India’s umbrella party, but, through the polarizing tenor of its recent conference, has also, paradoxically, repudiated the ideal of inclusiveness which formed the core of Nehru’s philosophy.

Re-defining history: The saffron offensive:

While the Congress’s appropriation of the national heroes of the past is marked by a struggle to remain relevant in the future, the BJP’s role in the same process is characterized by an entirely different motivation. It is marked by the dual purpose of gaining wider or mass legitimacy for its ideology and of actively re-defining history in the context of the new ideals it seeks to usher in. The party, none of whose leaders were invited to the Congress’s ‘secular’ conference, celebrated its own parallel event to mark Nehru’s 125th birth anniversary. While this was a clear acknowledgement of the fact that the party cannot marginalize erstwhile national icons of Indian political history to gain mainstream legitimacy and acceptance, the process of active re-interpretation of history has also been occurring simultaneously.

The process of re-appropriation of history has been occurring along entirely different lines and does not reflect the same strategy which the BJP uses for gaining passive legitimacy. It is, first and foremost, characterized by the absence of Nehru and his ideals which have defined the Congress ideology, and an appropriation of entirely different national icons and an alternative and sharply polarizing ideological discourse. This was clear from:

First, the manner in which the BJP celebrated Sardar Patel’s birth anniversary on 31st October and commemorated it as the National Unity Day. This was despite the fact that Indira Gandhi birth anniversary on 19th October is already celebrated as the National Integration Day. It reflects, not simply a bid to gain legitimacy, but also an active effort to re-define constitutional ideals, such as unity and integrity of the nation-state, in an entirely new light.

Second, the fact that BJP takes clear recourse to personalities such as Tilak, Sri Aurobindo, Gandhi, Patel and Bose, in its rhetoric, also shows that its political strategy centers around the revival of an alternative historical discourse, with ideological underpinnings different from the Nehruvian world view.

Finally, the BJP invokes icons such as Gandhi and Nehru only to mark the relevance and appeal of its mainstream political programmes. The ideological core of the party, emerging from figures like Golwalkar and Savarkar, influenced the saffron ideology of the RSS, is what determines the course of substantive national policy restructuring, such as seen in the functioning of the education ministry.

Thus, unlike the Congress, the BJP has appropriated national icons, of various ideologies, in an extremely filtered and discretionary manner. On the one hand, it has appropriated some icons to gain legitimacy and counter the Congress and commemorate its highlight or pet projects. On the other hand, its substantive and primary functioning, through which it has actively sought to re-interpret history, has been influenced by ideologues of the saffron thought. This raises the question of whether appropriation of national icons can be a successful way to re-write history.

Can appropriation succeed?

The precise reason why mainstream political parties would attempt to appropriate national icons, albeit for different reasons, lies in the fact that icons like Nehru and Gandhi hold a homogenizing appeal for the nation as a whole. Even icons like Sardar Patel and Subhash Chandra Bose, despite the polarizing rhetoric often attributed to them, hold this homogenizing appeal by being a part of the strong personalities that dominated the mainstream struggle in the crystallization of the India nation-state. This was also acknowledged implicitly by the current national leadership when the BJP attacked the Congress for trying to appropriate ‘national’ icons for purposes of dynasty politics.

Given that icons such as Nehru, Gandhi and Patel have a ‘national’ appeal precisely because of the universal or homogenizing ideology they represent, the extent to which they can be appropriated for polarizing purposes remains dubious. This is, in fact, the precise reason why the BJP appears to have adopted an implicitly dual approach with regard to various national icons, catering to both passive bids to gain acceptance and ensuring the interspersing of institutions with a more powerful polarizing rhetoric. Thus, while ‘national’ icons can be appropriated for re-defining history up to a limited extent only, the current dispensation has certainly deployed a different approach and targeted both the aspects.