Should Politicians' Personal Lives Matter?

Personal is political?

Different countries react differently to the colourful personal lives of their politicians. In the United States, the American senator who accidentally tweeted inappropriate pictures of himself was forced to resign. However, in Italy, Silvio Berlusconi who had women dressed as nuns performing a striptease is unfazed and is still going strong.

Over the years, the media has increasingly focused on the private lives of politicians and public servants. In certain situations, revelations are considered to be in line with public interest, but often, this ‘fine’ line between media responsibility and malicious gossip is not easy to define.

Strangely, in India, personal lives of top politicians have always remained out of media’s purview in what is a self- regulated omission of such news. We have string of single or practically single Chief Ministers including Mamata Banerjee, Jayalalithaa and Naveen Patnaik, yet so little is known about the private lives of these very public people. Is this due to their pristine and chaste existence, more so than public figures elsewhere in the world? It is hard to detect but presumably unlikely.

The Indian media seems to have adopted an unwritten code of conduct that shies away from reporting on the personal lives of politicians. This is not so in the West. Sexual transgressions of public figures have become a commonly reported issue and readers never seem to tire of hearing the dirty details and the apology afterwards. At the same time, politicians in the West can be let off for running down the country to an economic crisis, corruption or even war mongering (read Iraq, Afghanistan) but never for their ‘flings.’ The boundary between public and private life has gradually eroded since the 1970s, due to changing notions of family values and morality – strongly influenced by the spread of television as a mass medium and a commercially-driven sense of hedonistic individualism.

In the early sixties, the Perfumo affair involving Christine Keeler and Dr. Ward toppled the Harold Macmillan government in the United Kingdom. In 1989, a sex scandal revealed by a geisha forced the Japanese Prime Minister Sosuke Uno to resign after being in office for just 68 days. Former US President Bill Clinton’s affair with Monica Lewinsky in 1998, his initial denial and subsequent admission made big news.

More recently, the media spotlight in India has been on the extramarital affairs of French President Francois Hollande and India’s Minister for Human Resource Development Shashi Tharoor. Mr. Hollande views his secret tryst with actress Julie Gayet as his private life and has slammed the media by insisting that private affairs ought to be dealt with in private. On the other hand, there was media speculation that Mr. Tharoor’s alleged affair with Pakistani journalist Mehr Tarar led to the sudden and tragic death of his wife Sunanda Pushkar.

Interestingly, the Indian media maintains an Omerta about the “private” lives of politicians. Several senior political leaders continue to lead very colourful lives and this long list even extends to a few former Prime Ministers. While such details of their private lives are common knowledge in journalistic circles, it has rarely been covered in the media. This has led to many questioning whether there exists an unwritten code between the media and the politicians that private matters must always be treated as private. Or is it a reflection of India’s double standards and hypocrisy?

In India, the blurring of lines between the private and public lives of political leaders is definitely a new phenomenon, ushered in by the unprecedented spread of social media. While politicians benefit from internet based interactions with potential and often young voters on such social platforms, the dissemination of private information can come at the cost of turning politics into a contest driven by the public perception of individuals instead of manifestos and agendas. For many, the danger of this new trend could also set India on the American path where personal attributes and private lives of politicians influence voting preferences.

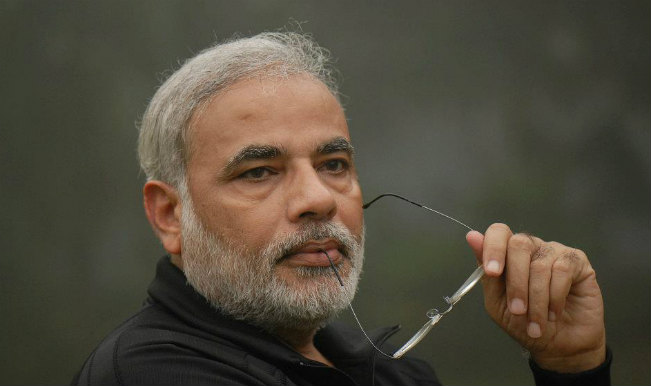

Besides, the western voters’ expectation of their representatives to fit the image of a dutiful husband and responsible father neither works for Mr. Modi nor Mr. Gandhi.

While the American President is happy divulging personal details and snapping family selfies, in India, the world’s biggest democracy, the opposite is true. Snippets of news might make for gossip in the corridors of power in New Delhi, but never get a public airing. A significant chunk of the Indian public also feels that it is not anyone’s business what their netas get up to in their personal lives.

Even debates in India about prominent figures in public life are rare. The furore following the publication of a biography suggesting Mahatma Gandhi was bisexual, sparked moves to make insulting Gandhi a non-bailable offence. The Congress party too came down like a ton of bricks on Madrid-based writer Javier Moro's novel based on Sonia Gandhi's life.

Social media has not only arrived in the lives of our Indian politicians but it also has the potential to shape their political destiny. The question that remains, however, is whether democracy will suffer as a consequence of this personification of politicians which could potentially shift the focus away from their political ideas or proposed policies.