Case Or No Case, Xerox Remains Mainstay of Life For DU Students

NEW DELHI: The Delhi University photocopy case has been in the news pages for several years now, with the Delhi High Court recently delivering a series of blows to the big publishers and copyright holders in their suit against Rameshwari Photocopy Shop.

Earlier this month, the High Court ruled in favor of the photocopy shop and university, declaring that the photocopying and making of course packs was covered under Section 52 of the Copyright Act.

The saga began in late 2012, when various prominent publishers, including Oxford University Press, Cambridge University Press amongst others filed a case against Delhi University and Rameshwari Photocopy Shop located in the campus of Delhi School of Economics of the university for copyright infringement.

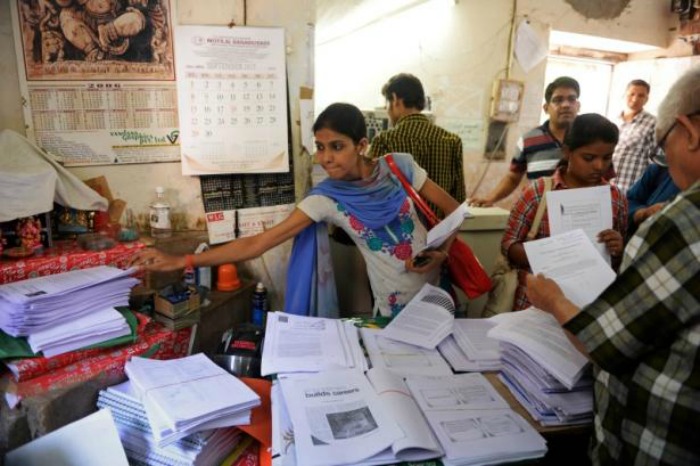

This photocopy shop, amongst others, makes course packs for students, including (sometimes sizeable) extracts from textbooks published by aforementioned publishers, that form part of the university’s course syllabi.

Photocopying texts for the purpose of instruction forms part of ‘fair use’ laid out under the law and must therefore, even exempt the university from the necessity of purchasing a license from publishers of these texts to allow for photocopying for students.

The verdict comes as a great relief to students in the university and others. However, having already made an expense of approximately ?4-5 lakhs on the case, Dharampal Singh, owner of Rameshwari photocopy shop expects to have to shell out more once the publishers appeal to the Supreme Court.

Along with Rameshwari Photocopy shop, others in the campus had also stopped making course packs for students for six to eight months while the court case was under way.

Santosh (name changed), operating the photocopy shop in one of the DU college campuses (frequented by students of the college and others in the university for notes, course packs, older questionnaires etc), who usually creates course packs for undergraduate students, had also stopped providing photocopied course packs to students in the college for a few months. He gave us his view on the issue.

One, is it cheaper (sometimes the books from which extracts are assigned reading, cost a few thousand rupees) and infinitely more convenient for students to get their required readings in a consolidated, bound form in their nearby photocopy shop. And two, often it is the only way some of the students in campus can get access to the text, with low availability, unaffordably high costs and not enough copies stocked in the libraries.

Heads of departments and libraries provide Santosh with required texts for the course packs.

Meanwhile, the extent of the application of ‘fair use’ specified by law is under dispute. Whether the High Court’s decision was based on an excessively liberal interpretation of fair use for educational purposes or not, will be addressed by the Supreme Court.

Other issues such as how much of a text should be legally allowed to photocopied for such use and whether the university must be required to pay a fee to Publishers must also be settled.

Technical issues such as these, however, may be of less importance than may first appear, considering the practical consequences of the matter. According to Santosh, despite the turn the Supreme Court’s verdict may take, it seems unlikely that students will be persuaded to buy the books or that the university will purchase a license. This is because instead of a course pack for the whole semester, copies of singular units of the texts can be photocopied by students when they require the same for class, with next to no additional inconvenience.

Photocopy shops around the campus will always be busy hubs for students and this, in all probability, will remain the conventional way of circulating texts among students.

At present, amid raging debates about copyright and fair dealings, little Xerox shops and stalls remain perpetually busy and relied upon by faculty and students in the university.