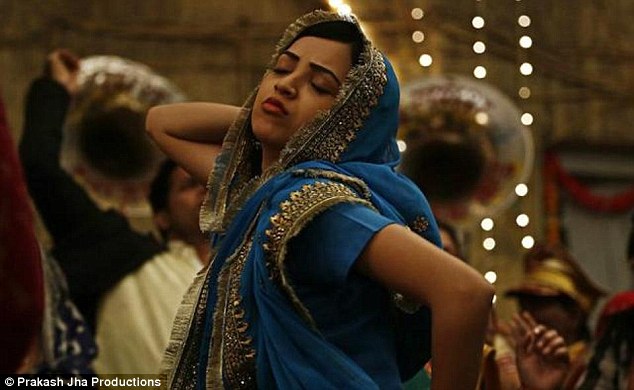

Lipstick Under My Burkha

SHOMA A.CHATTERJI

The film Lipstick Under My Burkha produced by Prakash Jha and directed by Alankrita Srivastava is a powerful political statement on how women can strategically use two extremely polarised items of women’s use - the lipstick and the burkha to express and articulate their undiluted sexual desires, irrespective of caste, class, age, community, faith and social status.

Therefore, the l CBFC today dictated by the powers-that-be at the centre are really scared of what impact this film will have on the audience in general and females of all ages in particular.

This film openly and without embarrassment explores not only the woman’s sexuality but also the ingenuous and devious ways women invent to try and fulfil their sexual and other desires clandestinely, using the veil to their advantage and the lipstick for their satisfaction in a way they like to and not because they are forced to.

Lipstick is one of the most widely used cosmetics since Cleopatra first stained her lips with carmine in 69 B.C. Often referred to as “hope in a tube”, lipstick has captivated women (and men) since the earliest rosy stains linked lipstick and women's lips with femininity and sexuality.

Honoured in 1997 as one of 12 objects included in an exhibition entitled "Icons: Magnets of Meaning," lipstick has transcended its decorative roots and become culturally indispensable as a quick and affordable way to transform one's image. First mass-produced in 1915 when American Maurice Levy designed a metal case for the waxy tube, lipstick was one of the few luxuries purchased by Depression-era women. Lipstick hit its stride commercially in the 1950s.

Dougherty Delano Page in Loose Lips Sink Ships: Women, Citizenship, and Sexuality in Wartime Culture, writes: “Lipstick, marking on a face's lips, the border of the mouth, suggests a visceral stamp, a trace which lasts in time. Lipstick connotes the material surfaces and lived practices of female embodiment, in this instance interacting with and echoing the physical intensity of warfare itself as well as the intricacies of wartime erotic desire.

It is worn for looking good, it is worn for going out and being seen, it is worn for parties, it is worn for work; it is put on privately, at the bathroom mirror, or it is applied publicly, in restaurants and in subway cars. It disguises. Or it amplifies. It is worn for kissing, to seduce.”

These features are prominently and freely expressed in :Lipstick Under My Burkha The film shows how an elderly woman (Ratna Pathak Shah) with grey hair is physically attracted to a young, macho boy and begins a vicarious relationship with him without revealing much about herself.

Tangee Lipstick's "War, Women, and Lipstick" ad in Ladies Home Journal in 1943 wove the "right to be feminine and lovely" into commercial propaganda. Such ads reflected women's sense of independence and need us to understand that power does not have a single originating source.

In the use of lipstick by the women in Lipstick Under My Burkha, one can read into the ideological effects of gendered practices, and into the validity of seeing "morale" through details such as women's access to pleasure, to self-fashioning, and how they imagine themselves in the action and dreams they are engaged in.

In Satyajit Ray’s Mahanagar, Arati’s husband Subroto did not take kindly to his wife using lipstick clandestinely after she took on a job and learnt to use lipstick from a Anglo-Indian colleague who gifted her with one. He found the ‘offending’ stick of red inside her purse when she asked him to take some cash out of it. She looked at his angry face and threw the stick outside the window.

Was it an expression of anger? Or was it a sign of submission? Was it silent rebellion? Did her husband have the right to open her purse even on her say-so? In 1963, no one had an answer. No one even raised these questions.

Times have not changed because even today, the censor board not only clamps down on a film that shows the borders women might be prepared to cross to assert their sexuality but also indirectly dictates what women should or should not wear or do, offering a classic example of how the politics of lipstick works against women while the film shows how it works for women.

Noted film critic Mythili Rao says, “Lipstick Under my Burkha does not get a censor certificate after it has done the festival rounds with a fair amount of success because "the story is lady-oriented their fantasy about life" and contains words of abuse and “audio pornography.”

The CBFC thinks that the semantic fudging of women into the more "cultured" ladies justifies their decision. Pray, are ladies not women? They are not allowed fantasies - be it about life, including sex - while mainstream cinema so often objectifies women to cater to male fantasies? Not just raunchy item numbers but discreet pandering to pious, so-called Indian values?”

“Words of abuse”? Give us a break Mr. Nihalani and team because even titles of films are known for the generous use of abusive words, not to speak of dialogue in mainstream films. I thought Budtameez was a term of insult and films such as Kaminey, Yeh Saali Zindagi and Lafangey Parindey passed the Censors’ scissors without as much as a by-your-leave. What about a box office hit like Amir Khan’s 3 Idiots which uses the word balaatkar as if it was a big joke and everyone in the audience guffawed each time it was repeated in different contexts that had nothing to do with either rape or women or raped women? Vishal Bharadwaj’s Omkara uses abusive language and cuss words that would make a sailor blush. Then why the brouhaha over abusive words when these are used only by women?

This brings us to that much-debated, criticised and questioned practice of the burkha in its various manifestations across major religious faiths across the world. The burkha or the veil or the ghunghat are items of clothing for women that enforced a certain degree of ‘invisibility” on them. Any laxity in the practice of keeping the head and face covered by the women concerned was strongly censured by elder females in the family and by the society the women belonged to.

But this film sheds light on a different edge to the use of the burkha or the veil. It shows how women and girls make use of this to express their emotions through facial gestures others cannot see. They can frown, smile, tease, grimace, stick their tongues out and even laugh silently under the cover of the burkha or ghunghat or veil and no one would know. A reprimand, an insult, could go unpunished because they are invisible. They could even take voyeuristic delight by sneaking peaks at other young men without anyone knowing. On the other hand, they could shed silent tears of pain, of suffering, of helplessness, of loss and grief.

Lipstick Under My Burkha therefore, uses both the lipstick and the burkha in their physical and social identities and also as metaphors of freedom and self-expression within invisible social restraints. The film shows the elderly lady dyeing her hair in a parlour and under the ‘safety’ of the burkha, applying lipstick and thrilled in the joy of feeling ‘free’ to be attracted to a young man and to want to look young and beautiful with her white hair dyed black and her fading lips gleaming a bright red, thanks to that dab of lipstick!

A radical revision of instrumentality, a different concept of self-fashioning with a vocal and at times openly sexual presence enables new configurations. This is especially true at a time when not only the dangers of a pro-Hindu dictate but also the threat to "democracy within our own personal attitudes and within our own institutions" simultaneously magnifies and numbs the human imagination, according to Simone de Beauvoir.

Women cannot and will not be easily enslaved or contained. Representations of women in films like Parched, Neel Battey Sannata, Pink, Masaan are strongly affirmative representations of women who affirm both presence and agency, voice and assertion, aspects of a more radical civic virtue and visibility. Lipstick Under My Burkha just underscores these values and beliefs redefined, reconstructed and re-read by women.