A Look inside Asia's Largest Scrapyard

SAMEER MUSHTAQ

As a society, we are always producing junk. How many times have you looked at dusty and abandoned vehicles, covered in dirt and rust, and wondered to yourself, where do these unwanted scraps of metal end up?

The answer can be found in Asia’s largest scrap market, where every single day, different types of vehicles are scrapped. From across India, old and unwanted cars, trucks, motorcycles that people dispose off, find their way to the Mayapuri’s scrap market. Everything -- from a humble bicycle to a large, imposing train -- is eventually discarded and scrapped in this market.

The alleys of the market are crowded with broken glass, abandoned engines, steering wheels, plastic and ripped rubber taken out of old vehicles. The market is full of old condemned (unused) cars neatly stacked against the walls.

The market was set up by the Delhi Development Authority in 1975, in Mayapuri. With more than 2000 shops, the scrap market is spread across a radius of around 4 kms.

Workers say that more than 200 vehicles are being scrapped per day. It’s been said that if your car was stolen, it’s quite likely that by the next morning you will find its spare parts floating around in this massive scrap market.

"It has been more than 28 years since my father established this shop here. I scrap more than 10 vehicles a day and earn around 20,000 rupees a day before demonetisation," said Sahab Singh, an owner of one such shop.

Anybody can buy second hand automobile parts from this market at affordable prices. Usable parts are taken out and the rest is scrapped to sell to the metal companies.

"We pay around 1000 rupees to labourers to dismantle the vehicle completely," another shop owner in market said.

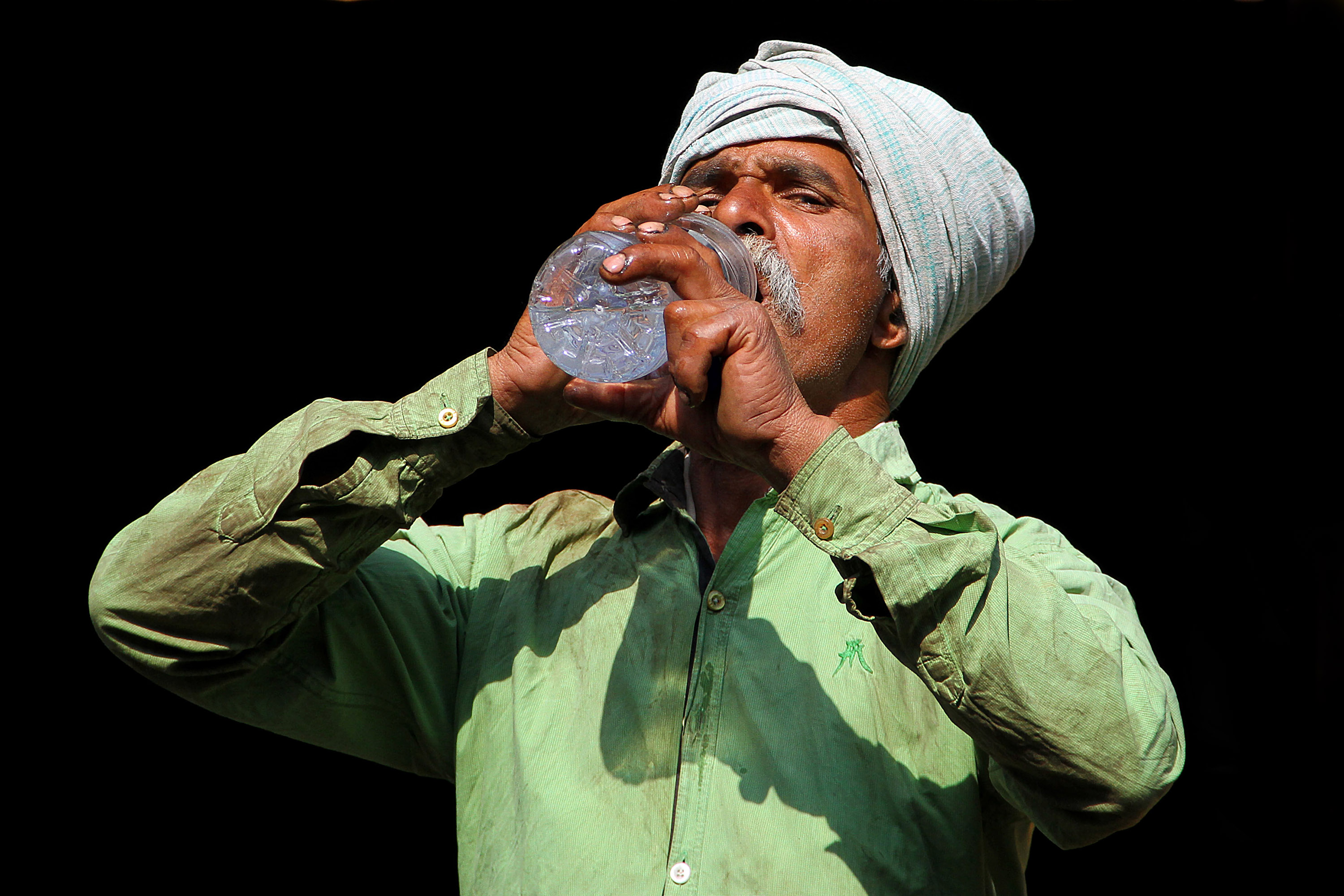

In the photos accompanying this article, one can see a man quenching his thirst on a hot sunny day. The market, is beset with problems typical of Delhi’s many small colonies. Lack of alley ways, bumpy roads, non existent sewers. In another photo, a labourer quietly carries a part of an automobile engine…

Each shop has its own personality, although they all do relatively the same thing. Colourful frames of Indian Hindu Gods adorn the equipment in these tiny stores.

Manmohan Lal Has been working here since the past ten years, and considers this scrapyard to be a second home, which not only helps him earn a livelihood, but also provides a sense of purpose. Manmohan is one of thousands of workers who earn their livelihood here. In the accompanying photo, one such worker is seen balancing a heavy metal portion of an engine on his head. Hundreds of workers from several north Indian states work in this scrapyard earning meagre money. A single vehicle can take several people to disassemble completely.

A grease covered stray dog lies on the ground in the Mayapuri scrap yard. The strong smell of grease and used engine oil can cause several respiratory ailments to hundreds of workers here, but for earning their livelihood, this risk is a too small price to fill ones stomach.

But in the end, even that’s not enough. “This work does not fetch us enough money for the survival of our family. We are able to save little money for our families back home and it is mostly the owners here who earn a handsome amount,” says a worker, Mohan.

More importantly, perhaps, the scrapyard is an indication of just how desperate lives can be. In 2010, the scrapyard made headlines when it was discovered that Cobalt-60, a radioactive substance, had made its way into Mayapuri, jeopardizing hundreds of lives. It took five people who fell severely ill, and a labourer who died, for authorities to discover that a radioactive substance had made its way into the scrapyard in complete contravention of norms.

Investigations have shown that victims of the radiation from the substance continue to suffer from symptoms, but the story has rarely made headlines. While authorities have tried to put in place certain norms to ensure that the disaster isn’t repeated, in reality, they are piecemeal and will not achieve much. The people who sift through the discarded vehicles and scrap material are none the wiser, with their risk being in fact heightened.

Instead, life continues as it always did at Mayapuri… the air remains toxic, the metal burning and rotting, and the people who work here… their lives remain at risk.