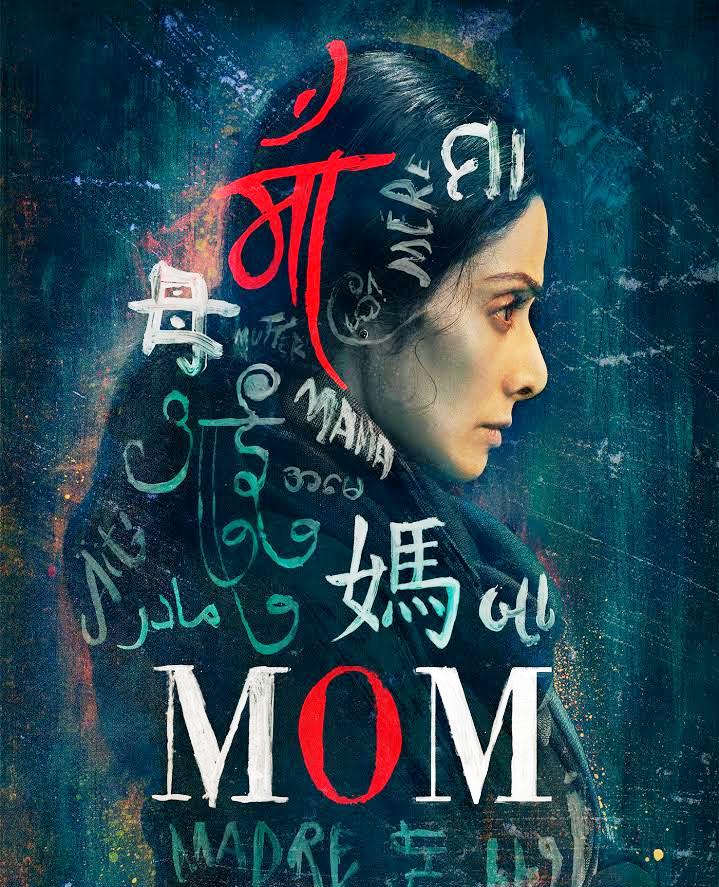

Call The Film Mom But It All Boils Down to Sridevi

SHOMA A.CHATTERJI

“I love the way she projects two facets: a visible persona and a subterranean one. She keeps her thoughts to herself; she seems to suggest that her secret, inner life is at least as significant as the appearance she gives.” This is a quote from Francois Truffaut, the French filmmaker, screenwriter, producer, actor and film critic who was one of the founders of the French New Wave.

One has no clue today about the actress he described thus, but had he been alive today to watch Sridevi in action in Mom, he would have felt the same about her performance. Mom is a revenge thriller with its origins rooted in several recent films like Jazbaa, Drishyam. Kahaani 2 and Matr. Each of these films has a strong undercurrent of a mother whose motherhood takes first place when she is torn between her composite identities as a woman, per se, as a woman with a vocation and as a mother.

This is playing to the gallery true, but this is also what the audience laps up and the critics go crazy about. The mother in Kahaani 2 is not the biological mother of the little girl but she takes in the girl as her own and risks her life at every turn to keep her safe and secure.

Devki in Mom is the step mother of Ariya, the older of the Sabharwal’s two daughters. Ariya, 18, refuses to accept her as a substitute for her own mother who died. She humiliates and insults her and insists on addressing her as Ma’am because Devki Sabharwal teaches biology in the school she goes to. The script charts the journey of how this Ma’am becomes Mom.

Ravi Udyawar, the young, debutant director manipulates his audience instead of reacting to audience expectations by marrying the ‘family melodrama’ to the thriller genre. In so doing, he turns the proverbial sacrificing mother image on its head by transforming her as a superwoman determined to single-handedly destroy all the four young men involved in the gang-rape of her daughter, attempted to kill her and threw her in a drain to die reducing her almost to an emotional and physical cripple.

Mom is not a clearly defined thriller such as the spy thriller, the detective thriller, the psychological crime thriller, the horror thriller or the police thriller. It is more a metagenre that gathers several other genres under its umbrella that colours each of those particular genres. Devki tries to go it alone as an avenging Superwoman. Over time and several hiccups, she relents to taking help from private detective DK – a marvellous performance by Nawazuddin Sheikh who underlines his versatility and complements Devki bonded as they are, by the same emotional sense of stress and distress – they both have a beautiful daughter.

There is a touching scene when DK’s daughter brings him a cup of tea on the terrace while he seems to be disturbed. They have both seen the news on television and without uttering a single word, they understand each other perfectly. Though DK might be misconstrued as a comic relief in a serious film, the character goes far beyond providing humour. He offers a humane touch who appeals to us by his honesty, intelligence and courage.

The director has used silence throughout the film to enhance a scene or cut into sound at the right time, the right place and with the right persons. This goes a long way in adding finesse to the editing, and the unfolding of the story which goes a longer way than dialogue would have gone. The suggestion that Ariya is slowly coming out of her trauma comes across when she sends a cell message to her father with their old joke saying, “you are looking very handsome” just when he is getting into his car to drive away. The father looks up to see her smiling from the window and smiles right back. Most of the interactions between DK and Devki are silent, or, in secret whispers and Devki knows exactly where to draw the line between the personal and the professional with this guy. In one small scene, he spells out his wit when he says, “I have a beautiful daughter as old as yours. Luckily, she takes after her mother,” tongue firmly in cheek.

The four young men, relatively unfamiliar faces except the driver (Abhimanyu Singh) who rape and molest Ariya and leave her to die are not history-sheeters, except one of them. They remind us of the Nirbhaya rapists who raped because they felt they had the right to do it and actually believed that they would go scot-free, These young men really go scot-free serving as a strong pointer to the impotence of the legal and judicial system in the country. These actors have performed very well except that Singh is a bit too over the top to go with the subtle mood of the rest of the film. Adnan Siddiqui as Ariya’s father Anand Sabharwal is excellent. When he tries to bash up one of his daughter’s rapists in court, he is at once caught and put behind bars. A shocked Devki shouts at the police men, “You arrest a man for beating up a rapist and let the rapists go scot-free.”

Akshaye Khanna as Crime Branch officer Francis, adds charm with his crooked smile, his suave screen presence and his seemingly casual demeanour which gets a bad a knee-jerk with his discovery of a pair of glasses in the flat of one of the young men and he gets on the right track. There is another silent scene between him and Devki who looks for her glasses inside her purse and he hands a pair to her. She takes out a pair from her bag and puts them on, with an enigmatic smile – what a smile!

The editing (Monisha R. Baldava) is crisp, tight and powerful, often cutting into the blue sky with cotton candy clouds floating across, giving the lie to the terrible reality below. Anay Goswami deserves several awards for his brilliant cinematography that moves from an art gallery to the kitchen of the Sabharwal house to the biology classroom of an elite school, to the shabby office of DK to the hospital room where one of the rapists is waiting to die to the metro stations of Delhi right across to the snow-capped mountains of a foreign locale. There is too much music for a film of this kind which sounds discordant when it becomes louder than needed and the the drama is so intense that the songs become superfluous.

In this otherwise intelligently scripted film, one wonders what makes a serious teacher like Devki use a huge Salman Khan poster to explain the muscles of the male body in a biology class. This runs cagainst her serious nature and her strict demeanour as a teacher who does not blink before she throws away a boy’s expensive mobile out of the window because he is caught sending dirty pictures to Ariya through his cell phone. That leads to a few other questions that beg logic. How does the driver of Charles manage to follow the family to that snow-capped hill station? How does Bahadur, the security man who is among the rapists, manage to walk back to his house after the night when he was castrated? Is this possible? The climax is an overload of melodrama the film could have well done without because all it does is drag the film to a running time of 146 minutes. Yawn….

Devki is shaped as a model housewife, an intelligent working woman and an ideal combination of beauty, brains, education, attitude and behaviour. If we do not raise our eyebrows at such synthetic and unrealistic perfection, the credit lies squarely on the slender shoulders of Sridevi as a performer par excellence with a slight issue with her pronouncedly South Indian-accented Hindi and signs of middle-age that make-up has not been able to hide. Sajal as her daughter comes out with a very convincing performance.

Sridevi’s portrayal of Devki reinforces the power of cinema to promote ideologies that do not exist except in an Utopian world. Mom reiterates the fear that films like Pink and Drishyam and Badlapur have already shown – that in a world where rapists go scot-free and unpunished in a court of law, the victim becomes the victimiser even if it leads to s a series of murders. Letting go of criminals sets the ball rolling to produce new criminals in society without eliminating the ones that exist!