The Cinema Of Partition

SHOMA A.CHATTERJI

By conservative estimates, anywhere upward of half a million lost their lives due the fateful event of 1947 when a certain someone decided to draw the Radcliffe line. Over 70,000 women were raped and about 12 million people fled their homes. Nearly 500,000 deaths must have taken place, a figure that Ian Stevens points out is equal to the number of casualties sustained by the entire British army during the six years of WW II (107).

It is difficult to tell where entertainment ends and the political element begin and vice versa. Does a director use entertainment to cushion his political statement? Or does a filmmaker make a pretentious attempt to spout something covertly political to add one more dimension to his entertainment factor?

Nimai Ghosh’s Chhinnamul (The Uprooted, 1950) in Bengali was about the partition of Bengal, about the harrowing lives of the people who, in its aftermath, acquired the label ‘refugee.’ It was unique in its narrative force, fluid camera movements, deft handling of actors sans make-up, effective use of dialects of East and West Bengal and extensive location shooting. Ghosh ushered neo realism in Indian cinema before Ray rediscovered it in Pather Panchali (1955) or Bimal Roy reinvented it in Do Bigha Zamin. (1953.)

The film caught the attention of one of the greatest masters of Soviet cinema, I.V. Pudovkin on a visit to India in 1951. He chanced upon a screening of Chhinnamul. “I see your county in this. I see your people in this,” he exclaimed. Pudovkin made the Soviet government buy the film and invite Nemai Ghosh to the Soviet Union. With sub-titles in Russian, Chhinnamul was screened in as many as 181 centres simultaneously in Kiev, Moscow, Leningrad, Uzbekistan and other places. Ghosh was extended a hero’s welcome. But his home city never had him back and he passed away in he died of a heart attack in Chennai on January 29, 1988

The core essence of the film was centered on the gruesome scene at Sealdah station. Refugees from East Bengal swarmed Calcutta in great numbers and lay huddled on the platforms. They were plagued with poverty, squalor and epidemics. There were rotting corpses too. Ghosh visited the spot with his crew to film the scene. His actors were slovenly dressed to match the refugees, tried to mingle with them. By concealing the camera in a van, Ghosh shot them in that difficult location.

A young man approached him requesting to be given a role in the film. Ghosh gave him the role of a refugee. The man who made his debut in a film on refugees later focussed his films on the uprooting of East Bengalis to Calcutta and the social, emotional and financial trauma they had to suffer. His name is Ritwik Ghatak who went on to make the most incisive and searing celluloid comments on the Partition through Nagarik, Meghe Dhaka Tara, Komal Gandhar, Titash Ekti Nodir Naam and so on.

Ghatak had a unique and perceptive vision that assimilated the searing spectacle of Partition, the black memory of refugee camps, the degradation of rootlessness, the dehumanization of the alienated and the emerging definitions of a new class struggle. With an iron discipline in his head and a majestic compassion in his heart, Ghatak externalized his private anguish into a global perspective.

This heightening sensibility turned his art into a language that could be understood in distant Punjab and the rest of India, in Poland, Germany, Korea, Vietnam, Palestine and any country that had been sundered by the trauma of separation and the bleeding scar of an overnight border.

Ghatak’s Meghe Dhaka Tara paints a brutally frank picture in stark black and white images, of the family as a cannibalistic consumer of one of its own members. The politics takes root within the family itself as it changes its character, economics and demography as a direct consequence of its being uprooted from home soil, East Bengal.

The characters are black and white. Nita, her father and Shankar are the 'white' characters. Gita, Montu and their mother are the 'black' ones. Sanat is somewhere in the middle of these two extremes. He is weak, spineless, indecisive and finally, as cannibalistic towards Nita as the others. In Meghe Dhaka Tara, Ghatak seamlessly weaves in metaphors of violence.

Ghatak himself was displaced from his roots, his soil, and was forced to replant himself on what he considered was an ‘aberration.’ His films reflect a Calcutta of discontent, a Calcutta of hate, a Calcutta of despair, degradation and dehumanization, a Calcutta of corruption. All this culminated into a Calcutta of anger, of seething fury and ironically, a Calcutta of passion, a city that goes on living, loving and hoping; much like Binu, the little boy in Titash Ekti Nodir Naam who leads Ishwar to a life of hope; like Ishwar who begins to look at life through Binu’s eyes.

Garm Hawa (1973) was the first feature of M.S. Sathyu of India. The film was controversial from its inception, as it was the first film to deal with the human consequences resulting from the 1947 partition of India. This action, ordered by British Lord Mountbatten, split India into religious coalitions, with India remaining Hindi and the new country of Pakistan serving as a refuge for Muslims. Is ‘refuge’ the right word for Muslims who did not wish to leave? Would they be accepted socially and economically by the original residents of the newly formed Pakistan.

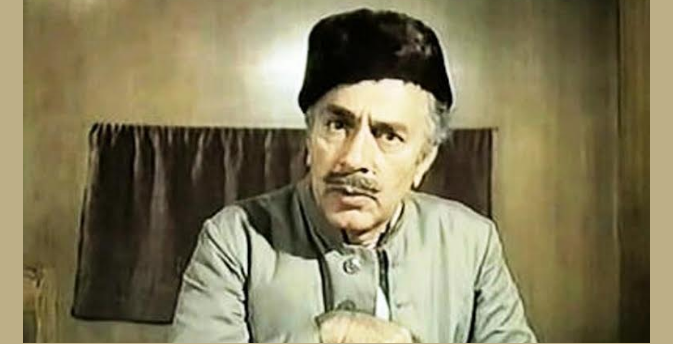

The story's protagonist Salim Mirza, was portrayed by Balraj Sahni Salim is a Muslim shoemaker and patriarch who does not want to relocate to Pakistan. There is the added element of a love story woven into this political narrative, however, and it is this element which adds greater meaning to the story also impacted by the Partition. The filmmaker's imaginative creation of use of light and framing added another dimension to the characters and their struggles. Salim finds himself totally vulnerable by the forces of this shift in attitude and in the sensitive and volatile political environment yet he refuses to cross over to the other side because he considers India to be his home. It is one of the best films on how Partition victimised the minority in India and what impact it had on human lives, lifestyles, ideology and economics.

The division of Punjab featured directly and obliquely in the works of Yash Chopra. Dharmputra (1961) that spans the period before and after independence. Shashi Kapoor plays a Hindu fundamentalist who discovers that he is actually a Muslim who was adopted by Hindu parents at birth. His entire ideology is transformed dynamically once he realises he is Muslim. But the message did not carry across to the audience and it was a commercial flop.

Shankachil, a Bengali film directed by Goutam Ghose, just won the National Award for the Best Bengali Feature film. Shankhachil is a story of the physical and emotional journey of a family along the Indo-Bangladesh border and is also a humane story of the brave BSF (Border Security Force) and BGB (Border Guard Bangladesh) personnel’s total commitment to guarding the borders of their respective countries. The citation said that the award was given for narrating “An evocative story that highlights the theme of suffering humanity, divided by national borders.”

Partition films made by filmmakers born after Independence such as Deepa Mehta’s Earth (1998), Anil Sharma’s Gadar Ek Prem Katha (2001), Train to Pakistan (1998), Pinjar (2003), Khamosh Pani (2003), Rajkahini (2015) and Shankhachil (2015) among many others. The quality is not very consistent but most of these films are tinged with commitment on the one hand, international acclaim on the other and of course, commercial success that would help them get producers for their next film.

Except Gadar Ek Prem Katha which was a brazen and crude commercial with Paki-bashing as its sole aim, the rest of the films were consistent in their statement. A kind of distancing is felt deeply in Train to Pakistan because it was directed by Pamela Rooks and in Earth because Deepa Mehta being an expatriate, is alienated from the first hand history of what led to the Partition and its impact on those affected by the Partition.

Khamosh Pani directed by Sabeeha Sumerr is not strictly an Indian film as it is a co-production but the cast and credits are mainly Indian. It recounts the dilemma of a Sikh woman who marries the Muslim man who abducts her, but is forced to confront her past when her son becomes a religious fundamentalist. Pinjar (2003), Chandraprakash Dwivedi’s glossy adaptation of Amrita Pritam’s novel, is also about the experiences of a Punjabi Hindu woman whose family rejects her after she is abducted by a Muslim man.

“Partition” has become a two-edged word for filmmakers who often reveal an interest in holding up a mirror to the Partition India in general and Bengal in particular presented through their cinematic lenses and personal perspectives. The question is – how many of these films are seriously aimed at reviving the spirit of the people divided, impoverished, left hungry and homeless because of the Partition and how many are aimed at raising the standards of the filmmaker and his team in drawing attention of international film festivals and awards to these films?

This is a dicey question the answer to which would largely be determined by the contemporaenity of the filmmakers concerned. If he experienced the impact of Partition on the consequences of it at first hand, his perspective would be serious and his statement, insidious and critical. If he is a young man born long after 1947, his filmmaking would derive from documents, books and films available on the Partition and be impacted at second hand.