Magic Realism At Its Best

Ami Joy Chatterjee is most certainly Manoj Michigan’s best film till date

“The term willing suspension of disbelief has been defined as a willingness to suspend one's critical faculties and believe in something surreal; sacrifice of realism and logic for the sake of enjoyment” according to Dictionary.com..

The term was coined in 1817 by the poet and aesthetic philosopher Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who suggested that if a writer could infuse a "human interest and a semblance of truth" into a fantastic tale, the reader would suspend judgement concerning the implausibility of the narrative.

Suspension of disbelief often applies to fictional works of the action, comedy, fantasy, and horror genres. What better than cinema to take it to extremes of entertainment, fear, horror, humane values, relationships and the rest?

Manoj Michigan’s new film Ami Joy Chatterjee (Bengali) works this suspension of disbelief both within his audience as well as within the film and in the intriguing journey of its protagonist Joy Chatterjee. The “ami” or “I” in him reduces everyone else into a zero, so sucked he is into his world of “I”, his Ego.

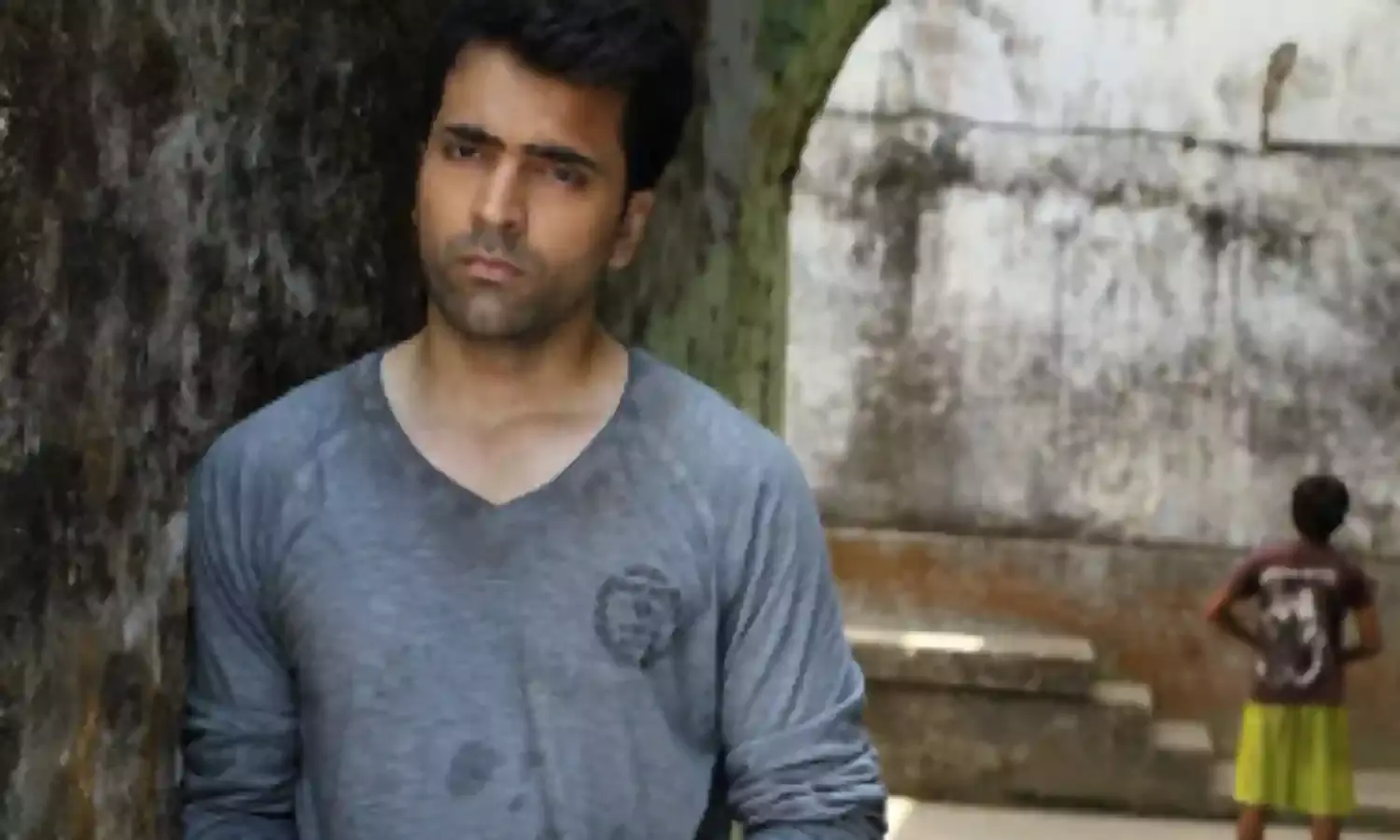

A dramatic incident changes the very meaning of this “I” and places “Joy Chatterjee” in a no-man’s land raising questions about his very identity – physical, social, emotional, psychological and professional. The question that arises here is – is this a story of split identity’? Or, does this handsome, super-confident young corporate industrialist suddenly find himself in a dark tunnel of amnesia that has stripped him of some slices of memory including who he is, where he is, how and why?

The film unfolds an intriguing tale of a man who metamorphoses into a different person juxtaposed, through flashbacks into the past, against his former, arrogant, rude and brutal self as the industrialist sans family or even a reference to any family into a man with humane feelings he did not know existed. He hates but is forced to believe this dramatic change in his life.

It all begins during a hurried trip to Kurseong with his fiancée, a soft, tender young paediatrician who, unlike Joy, is inclined to helping a small batch of orphaned children alongside her practice. She has a way with children and with helping them with medical assistance, and in kind. Joy does not care for this because he is convinced that philanthropy is actually allowing oneself to be duped by exploiters.

Vacillating between his past and his present, dotted by the sudden presence and disappearance of a Buddhist monk with a small child, Joy journeys through time and space and persona from one world to another, often puzzled with when one begins and the other ends.

The film is split into two halves, much like the questioning identity of Joy Chatterjee and his “I”. If the first half fills Joy with questions, the second half throws up some answers, unwittingly, to questions that arose in him but he did not know how to articulate them. In the second half, trying to hide from everyone including the police that believes Joy Chatterjee has been kidnapped, he finds himself seeking shelter in the same orphanage he condescendingly gave a small fund to, on the request of his fiancée.

The audience unwittingly joins him in his strange journey into this small world of orphans who teach him, through tiny nuggets of play and mischief, what happiness is all about. The little girl laments that the mute boy has torn off her doll’s hair while the eldest orphan Bhola is happy cooking and tending to the children without complaint. The elderly woman who had founded the orphanage takes in Joy willingly and Joy begins a different journey in this tiny world.

This is magic realism at its best that leaves several logical loopholes one would hate to reveal through spoilers. It is easy to glide smoothly across these loopholes through this magic thing called “wilful suspension of disbelief.” One is sometimes reminded of the film Inception where a return to ‘reality’ is suggested through a tiny top that spins when touched and acts as the characters’ return to reality.

The ‘orphanage’ segment is Joy’s first brush with the reality of the world that lay beyond his “Ami” and his reactions slowly shift from disappointment, shock, surprise, acceptance to inclusiveness – a sense of belonging he experiences perhaps for the first time in his life. One other ‘marker’ to his identity, in the past and the present is that scar on his face that the leader of the orphan gang points out to again and again.

On first appearance, in the small prologue, one feels this is a psychological thriller. Which, it is, in a manner of speaking. Then it turns into a ‘journey’ film where the journey is both an inner journey Joy finds himself caught in and an outer journey through Kurseong and Kolkata moving back and forth through the vast vistas of the hilly landscape and the narrow bylanes of a small suburb where the orphanage stands.

His intriguing encounters with that little boy and the monk who disappear into thin air as suddenly as they appear spell out the spiritual layer that introduces Joy to the magic world of a superior being that has control over everything and everyone, that imbibes in one the willingness to surrender the “I” for “us.”. It is also an unwitting spiritual journey of Joy with surrealistic experiences he encounters and keeps questioning himself about.

As the narrative moves on, seemingly at an electrically charged pace in the first half to slow down in keeping with the rhythm of the lives of the small kids living in the dilapidated home of the old lady, the suspense intensifies with every movement, every dynamic action, every twitch on the face of Joy marking the most outstanding performance of his career by Abir Chatterjee in his most challenging role. What a performance. The way he touches his face when he sees his reflection in a reflective glass, or his quiet joy when the little girl comes and embraces him, or, his desperation when the naughty mute boy plays tricks with him.

Counterpointing this we are given glimpses into in his “I” identity. He refuses to give second chance to his employee Rahul who remained absent an extra day because his daughter was in hospital, or, the arrogance with which he gifts the fiancée with the diamond ring is a performance to watch. .

Matching him in every frame is Jaya Ahsan as his fiancée but one wishes the script should have at least offered a reference point to her social history which is painfully absent. The rest of the acting cast offer the best support to his performance it possibly can. Sabyasachi Chakraborty is memorable in a very brief cameo.

The drama of the story is so highly charged that one tends to forget the aesthetics of the film created through technical factors. The music, only on the soundtrack, by Raja Narayan Deb is beautiful but a bit too loud for the philosophical mood of the film. Looking back, the film could have stood on its own even without the music track.

Manas Ganguly’s cinematography captures the vast skies of Kurseong complete with its narrow roads snaking its way between the hills and greenery panning across to catch the blue of the skies to cut into a narrow lane where Joy walks through, looking for a morsel of food, or, his spanky apartment that does not have a single photograph on its walls, or Joy suddenly catching his reflection on a large sheet of glass meets the demands of this difficult brief aptly.

Sanglap Bhowmik had a difficult brief cutting into the strange goings and comings of the protagonist through the film and does it aptly with his swipes and jump-cuts with a few jerks.

Ami Joy Chatterjee is most certainly Manoj Michigan’s best film till date which is saying something for a director who loves to toy around with very unusual storylines and dramatically different genres. The spirit of tension and suspense the film carries through from beginning to end is beautiful. It is indeed a great tragedy for Bengali cinema and its audience to be deprived of watching this film which, thanks to lack of publicity and promotion, is running in a few near-empty theatres and might finish this run by the time this review comes up.