My Sufiana Moment: Maulana Azad, Sufism and Tom Alter

Alter always said he got his strength to live in India because of Azad

Recently I experienced a most sufiana moment during a conference on Sufism and Social Harmony hosted by the Centre for Study of Society and Secularism (CSSS).

I managed to crisscross through the dense traffic on Maulana Azad Road in Mumbai’s Agripada neighbourhood to listen to Syeda Hameed inaugurate the conference held on the YMCA Road.

Syeda Hameed, activist, educationist and writer talked about Sarmad Kashani, a sufi who was executed in 1661, in Delhi.

She discovered Sarmad in the writings of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, a great champion of Hindu-Muslim unity, individual liberty and religious tolerance.

When he was barely 23 years Azad wrote an essay called Shaheed Sarmad. Syeda found the essay an enchanting read sprinkled as it is with Sarmad’s quatrains and other Persian couplets. The Urdu prose used by Azad to introduce the 17th century Persian poet to contemporary readers, is excellent.

Syeda is also author of Maulana Azad, Islam and the Indian National Movement. After reading it, she translated Azad’s essay on the sufi martyr of love into English in 1991, for the Indian Council of Cultural Relations.

At that impressionable age what must have attracted Azad to Sarmad was the universal humanism of the sufi thinker. Sarmad gave up his worldly possessions in a state of ecstasy. Even the clothes on his body seemed like a burden to him. He threw away his clothes because he wanted to be free of all worldly concern.

Sarmad’s fakiri influenced Azad. He learnt to be fearless like Sarmad who was not afraid to own anything in life. Sarmad was least afraid of the ruler, or the clergy of the day.

In his own life, a request was once made to Azad to change his shervani full of patches for an official event where Prime Minister Nehru would be present. Azad’s immediate reply was that the audience was coming not to look at his clothes but to listen to him speak!

The first Minister of Education of the country had owned six shervani and two of them were held together with patchwork.

Azad found a unique temperament in Dara and he mourns the unfortunate day when Dara’s enemies triumphed. He admires Sarmad’s pluralistic approach to life and his free spirit. It was so easy for him to sit down with other human beings believing in a different view of the world.

Sarmad was born in an Armenian family of traders, in 1590. He was a Jew who studied Christianity. While in Iran he was attracted to Islam and in Sind he found Hindusim.

He wrote:

O Sarmad! You have won a great name in the world,

Since you turned away from infidelity to Islam.

What wrong was there in God and His Prophet

That you have become a disciple of Lakshman and Ram?

This mad sufi was eventually beheaded for walking around naked like a yogi. Sarmad said that he found nakedness efficient, as it did not wear out like virtue.

He refused to wear clothes saying that to be dressed does not make a person pious. Sarmad’s nakedness was a sign of the sufi’s disregard of public opinion. He said that there was no miracle to his nakedness for the only revelation made by him is the revelation of his private parts.

He took his clothes off because a sweet someone had carried him away from himself:

He is in my arms and I run about searching for him, a strange thief has stripped me of my garments.

Sarmad believed that those who are with deformity, the creator covers them with dresses but to the immaculate is given the robe of nudity.

Sarmad travelled from Iran for the purpose of trade like most Armenians. In 1634 he visited Thatta in Sind where he fell in love with a Hindu called Abhai Chand. The young Abhai was forbidden by his father to meet Sarmad, making the lover crazy with grief. Later the father took pity on Sarmad and allowed Abhai the freedom to travel extensively with the poet.

After visiting Lahore and Hyderabad, Sarmad arrived in Delhi where news of his poetry and devotion to love, reached Dara Shikoh, the eldest son of Emperor Shah Jahan. Sarmad soon became a regular visitor to the palace and he basked in the company of monks and sufis, participating in numerous discussions on philosophy, Judaism, Christianity, Islam and Hinduism.

Sarmad had taunted the stern Emperor Aurangzeb so:

I go towards the mosque but I am not a Muslim.

For Azad, Sarmad’s love for Abhai was the first in an endless journey of love to realize the divine beloved.

Throughout the thirteen centuries of Islam the pen of the jurists has been an unsheathed sword and the blood of thousands of truth-loving persons stains their verdicts (fatwa) … Sarmad, too was murdered by the same sword.

Dara was beheaded as soon as Aurangzeb succeeded Shah Jahan as emperor. Soon after it was the turn of Sarmad’s head to be chopped off on the stairs of the Jama Masjid.

Azad lists three reasons for Sarmad's execution. It is Sarmad’s recitation of only the line that negates God. Azad argues that Sarmad had reached the stage only of denial that is why he did not say that there is a God because he was not sure. Sarmad's crime was that he drank the cup in public, while others did in private. The second reason for Sarmad’s execution was that he was naked, which was socially unacceptable. The third reason is traced to the lines in his poem on the Prophet’s visit and back from heaven. The clergy interpreted the lines as heresy.

Mullah says that Mohammad ascended the Heavens Sarmad says that the Heavens descended to Mohammad.

It annoys Azad said religious heads climbed on the pulpit of the mosque and madarsas to dream about the heights to which they can still rise. But Sarmad had reached the pinnacle of love from where the walls of the mosque and the temple are seen standing face to face.

As far as Azad is concerned the religious heads are a hopeless lot.

To believe that the traditional mind can still give way to regeneration is to believe against the laws of nature. We have no alternative but to ignore the rigid thinking altogether, focusing on the creation of a new mind which requires a radically different variety of literature and apprenticeship.

After having heard all this I stepped out of the conference hall. I marveled at Azad for being able to appreciate and applaud Dara and Sarmad’s free spirit more than a hundred years ago.

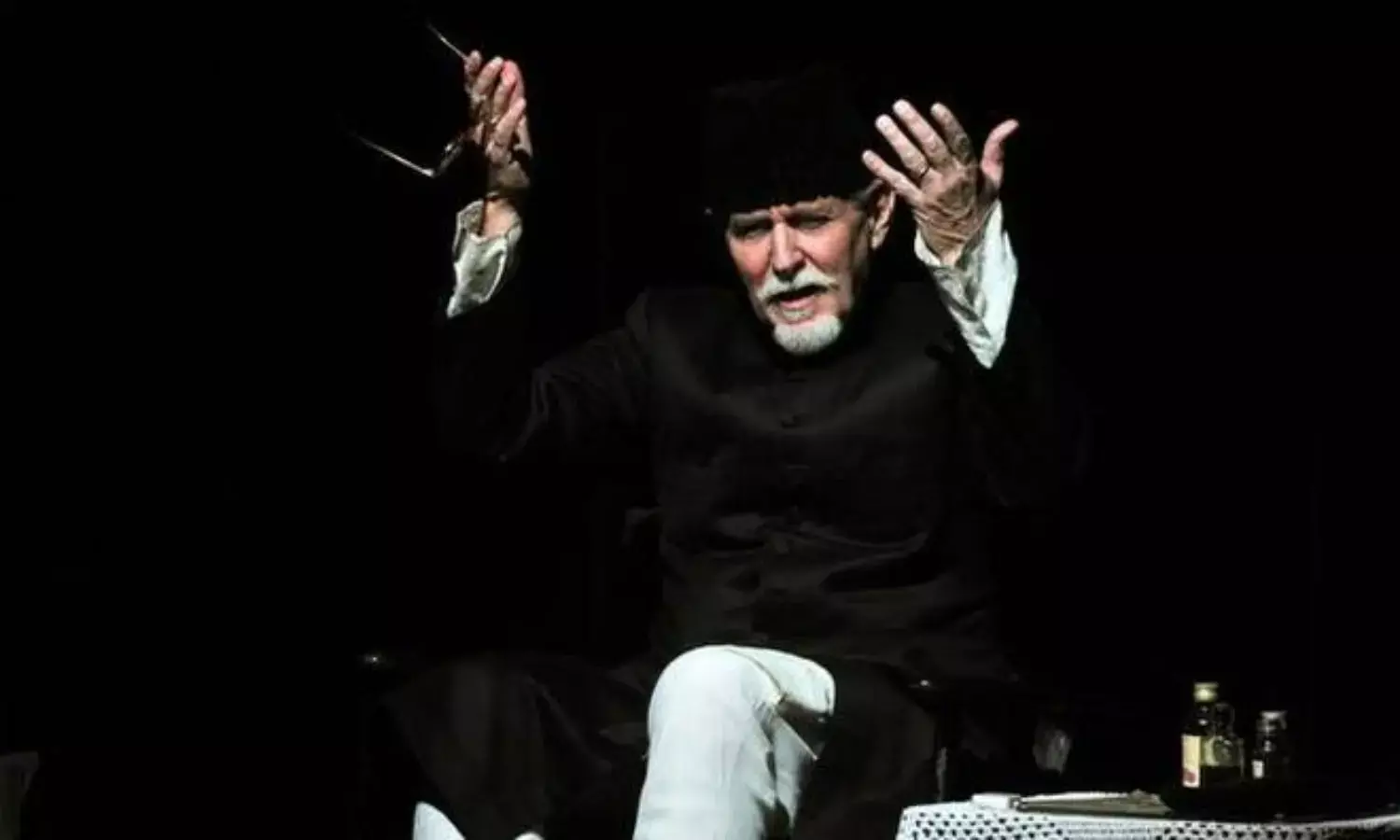

Now I was on the street, standing exactly opposite number 21, YMCA Road below the fourth floor apartment of the late Tom Alter who had played Azad on stage more than 200 times.

Tom had never tired of saying that it is from Azad that he got strength to make a home in this country and to live here as a proud Indian even though he came from a family of American missionaries.

(Cover Photograph: Tom Alter playing Maulana Azad)