The Wound: Black and White Memories of a Wounded City

Khwato, in black and white

Photographs are no longer what they were meant to be - purely a recording instrument documenting faces and events.

Creating a visual archive of nostalgia for birthdays, marriages, ritual ceremonies and family reunions that would find their place in the dog-eared pages of an album have also faded with the influx of the digital world and the mobile camera and the tab and other newer forms of visual technology. In this ambience of fading history, a documentary film that is a tribute to the still camera and to Black-and-White photography which is actually an agency sending out a message to all of us about the fading away of concrete history is an amazing shape of aesthetics and imagination.

The Wound is directed and cinematographed by a gifted photographer called Bijoy Chowdhury. He uses is camera not just as a recording instrument but much, much more as a narrative device to tell a story. He has earlier done several investigative series of photographs one of which on the Bahurupis of Bengal.

The Wound is a socio-political and historical statement on the negative aspects of “development’ of a city. Shot in Black-and-White, the film is a moving document on the planned destruction of significant milestones of Kolkata reduced to a mess of dismantled windows, doors and bricks and mortar of antique and old buildings that carry a history of their own” This 20-minute film has been selected for screening at the 11th International Documentary and Short Film Festival of Kerala to be held between 20th and 24th July this year.

The director says, ”The film is about memories - a record of places, people and professions that once gone will never return, and of the mysterious beauty of the man-made ruins that mark the transition from the Calcutta of authentic tradition to the new one of "modernity". It's a very personal story told through the eyes of a photographer.”

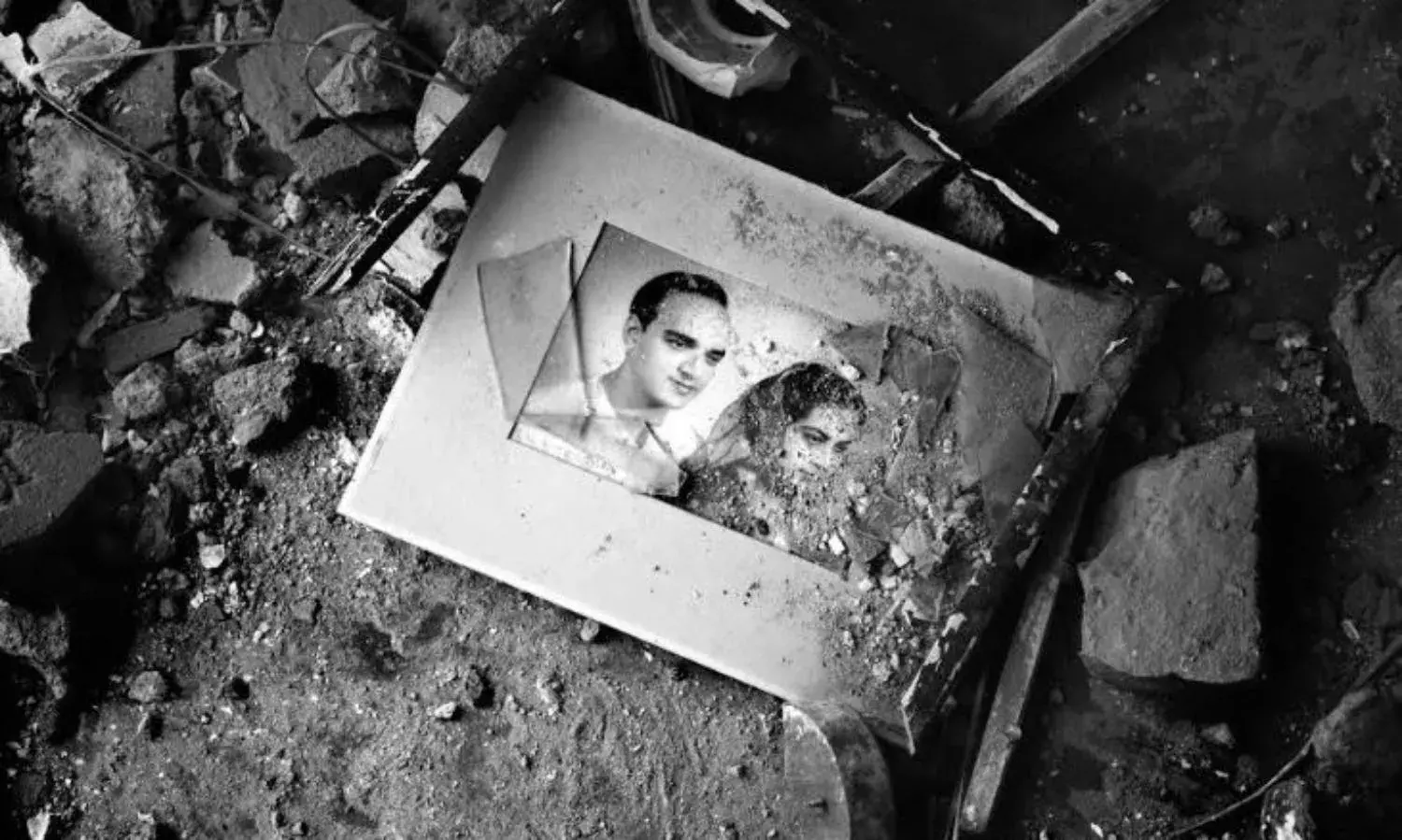

The “wound” is a metaphor of a city that has its own architectural history that is fast losing its identity to leave space for “development’ that brings down old, aristocratic buildings across heritage spaces, leaving a wound that may never heal. It is also a metaphor for the filmmaker, Chowdhury, who feels “wounded” as he experiences the hurt and the tragedy of falling windows, crashing doors, the debris of bricks and mortar, the sight of old, Black-and-White photographs lying on the floor of a room being broken, all this with the deliberate intent of “developing” the city. “Wound” may also signify the end of the traditional use of the camera and the Black-and-White film that will perhaps be wiped out as another sacrifice axed in the name of “beautification.”

Bijoy Chowdhury, a graduate of the Government College of Art and Craft, Kolkata, has been working in the field of visual communication and photography for many years. His works have bagged the Nirman and Photo Division Award and internationally, he has been honored twice with the Commonwealth Photography Award. He has also won the National Geographic Traveller Photo Award.

As the moving camera pans across, we are witness to a series of still photographs coming alive only through a flight of birds in the sky rising above the buildings below. The voice-over, in Bengali is the director’s own as he narrates how and when he began to think of capturing the old sights and sounds and visions of a city he was educated in. The voice-over is informal, delivered in a conversational tone, sans emotion because the emotions are enmeshed in the visuals. There is very little movement in the film but the sounds compensate for the lack of movement where moving presence is expressed through the demolition workers commenting on the coming down of the buildings, how the windows will turn to scrap to be sold away for money, the disturbing cracking of a slab being demolished as we watch, captive, as we find a family that once lived in an old building being fragmented into pieces.

Chowdhury has grown up and still lives in a suburban town. His love that grew into a passion for the city grew when he was studying at the Government College of Art and Craft in Kolkata in the beginning of the 1980s. “Photography was a subject and I began to fall in love with it and with the camera. I started taking photographs of the streets and lanes, people and all… That’s how the attachment grew. The streets, like Sudder Street, Chitpur Road, the various lanes of north Calcutta, College Street… I used to wander through these a lot… and take pictures… it became an addiction.”

He goes on to add, “At that time, the old buildings of Kolkata… Say, I am walking through a lane of north Calcutta… the tea shop in that lane, the women of the colony coming to fetch water from the lion-headed water tap… the gossip and chats, the community culture… then the car-shed verandas, the hanging verandas of the old days protruding on to the streets, the unbelievable designs of the laced grills, rust-free forever, those doors, windows and patios, those decorative designs on the pillars… they attracted me like a bee is pulled to a flower.” The strange wave of ‘development’ came at a heavy price – the demolition of old buildings and heritage homes once built by doctors and lawyers and businessmen of aristocratic families that were not just buildings but were an integral part of the history, the culture and the lifestyle of the city.

He explains that the streets of Kolkata he had walked through for years were suddenly cordoned off by tins and tarpaulins and we can see these in his beautiful photographs of these places, ironically juxtaposed against a demolition going on in the foreground. Name plates of owners, now deceased, engraved in black on white marble and framed beautifully, lie on the floor of a house in the process of demolition. “You suddenly see that an eighty-old building with two or three stories disappear and a multi-storied complex with matchbox-size apartments come up, resembling a bird’s nest.

“Over the past five to seven years, I see it happening in every lane and by-lane, not only in Kolkata but also in the suburbs, endlessly, without break where you the only sounds you hear are the sounds of hammering while walking down the streets as if a commotion is going on and we have no clue when and where it will end,” he says dispassionately as the pictures narrate their own stories.

Chowdhury covered the entire deconstruction of a close friend’s house in Bhowanipur in Kolkata. Suvendu Chatterjee, who headed the international photographic NGO, Drik-India in its Indian branch, had his office in this residence. They shifted to this home when he was a small boy with his mother after his parents had divorced. “It was a place where we practically grew up with our addas with friends. Suvendu’s father was a reputed doctor in America. Both of Suvendu’s parents’ photographs were there in this house. So, both his father’s and his mother’s photographs were kept together and packed off to the temporary residence of Suvendu. They probably never met again while alive… but now they were together in being shifted to another place!’,” Chowdhury sums up, a bit wistfully.

The Wound brings to life what Edward Weston said way back in 1924. “The camera should be used for a recording of life, for rendering the very substance and quintessence of the thing itself whether it is polished steel or palpitating flesh.”