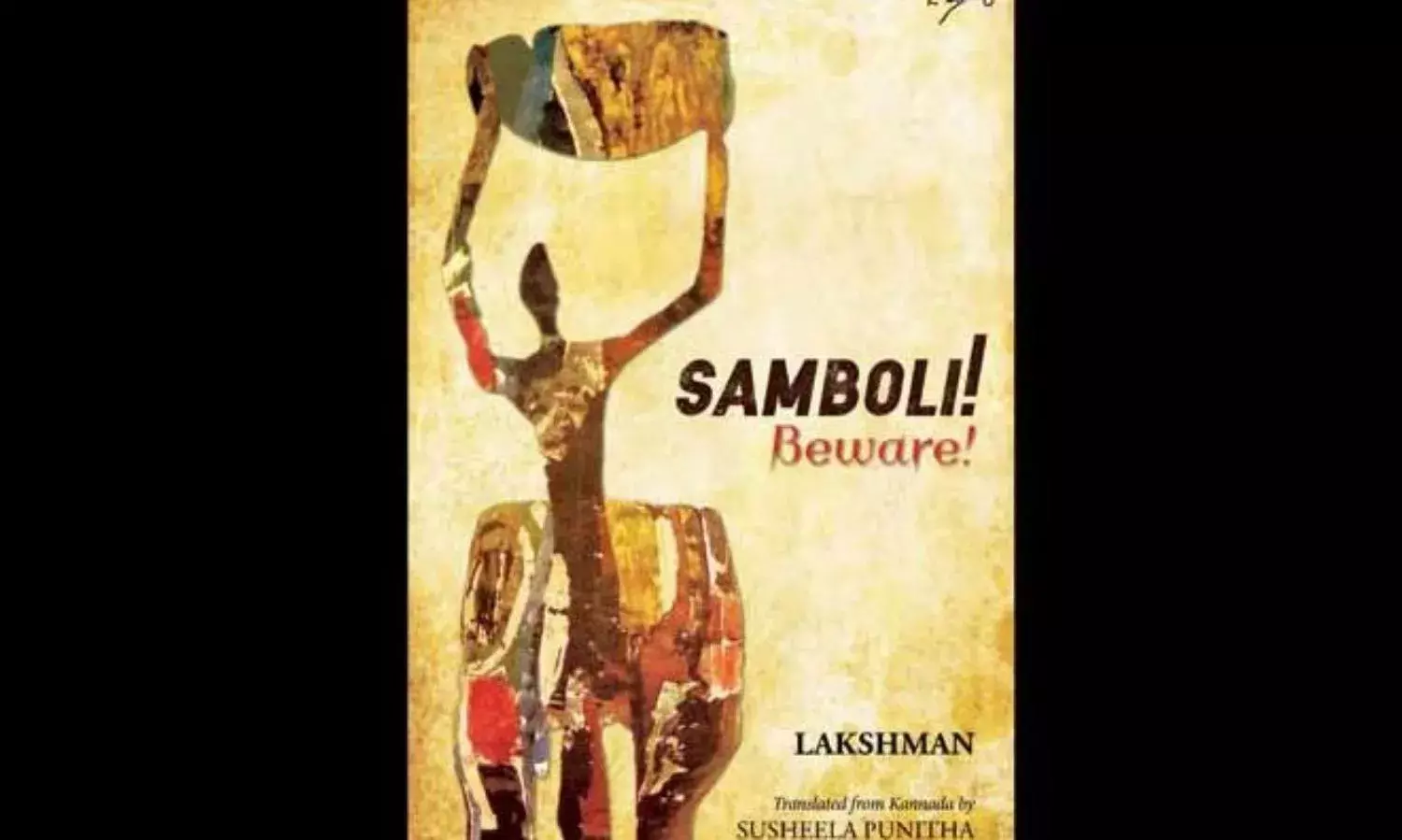

Samboli, Beware! Understanding Dalits' Predicament through Autobiography

A public debate has begun on the use of the term 'Dalit'

Some days ago the Information and Broadcasting Ministry asked media channels to refrain from using the word “Dalit” and instead use only the term “Scheduled Caste”. The advisory was based on a directive from the Nagpur bench of the Bombay High Court. A public debate has begun on the use of the term.

In modern India, during the anti-colonial movement Mahatma Gandhi called them Harijans (children of God) which was not accepted by Dr B.R. Ambedkar who had earlier used the terms “depressed classes” and “broken men” for the untouchables. Later Ambedkar settled on using the word Dalit. The British coined the term Scheduled Caste which is still used in the Indian Constitution.

In independent India, activists stuck with the word Dalit and it was popularised during the Dalit Panthers movement in Maharashtra in the 1970s. The Dalit Panthers Bombay Manifesto of 1973 defines the term Dalit as “members of the Scheduled Castes and Tribes, Neo-Buddhists, the working people, landless and poor peasants, women, and all those who are being exploited politically, economically and in the name of religion.”

Lakshman was from the Madiga caste and faced multiple forms of violence and discrimination because of his caste identity. He narrates a few such incidents in this book, such as when, as a child, he was beaten and forced by a member of Vokkaliga community, Naryanappa, to pick up and clean a shit stinking slipper with his shirt.

He was also thrashed and humiliated for getting sweet tamarinds from a tamarind tree, “which is a wild tree and grows anywhere it wants”.

In theory, schools are a secular space in which all forms of difference are mitigated. But this is not the case in most schools in India. Especially in the villages, differences are maintained and discrimination is practised. Lakshman talks about a Brahmin teacher in his school who made the Madiga and other Dalit caste students to sit in rows behind their upper caste classmates. The Dalit students had to have their lessons checked by putting their slates on the ground which he did not touch.

The teacher had two canes, one for beating the upper caste students and the other for the Dalits.

In his adolescence Lakshman failed his high school exams but managed to get a government job, which he soon lost because of treachery and deceit. For a while he could not fathom why he had been thrown out of the job. He writes, “It is only after I joined the Dalit Sangharsh Samiti in its struggle for justice and wandered through villages meeting other Dalits, whose lives were on the streets like mine due to the malice of caste distinctions, that I realised why I had landed a government job in the first place; what it implied when I sat among the other guests at the lunch arranged by the bridegroom’s family, and ultimately why I had lost my job through no fault of mine.”

He later married Kamala who was from another caste and her family members too maintained caste distinctions against Lakshman.

Discussing his political and social activities, Lakshman says he found inner peace after joining the Dalit Sangharsh Samiti. The Samiti fought for the rights and privileges of Dalits and staged protest marches against the injustice perpetrated on them. He writes, “Whenever I interacted with people of the upper castes or developed a friendship with them, I met with new problems and faced fresh insults. But now that I had participated in the protests by the Samiti, I felt a new peace; a sense of self-worth I had never known before. I felt new courage, a conviction that I was no longer orphaned.”

However, Lakshman’s fascination and illusion about the Samiti soon vanishes into the air. He finds that some members have been using the organisation for personal benefit. An early step in this direction was the Samiti’s inclination to support the Janata Dal during the elections in late 1980s. “When the Dalit Sangharsh Samiti was inclined to support the Janata Dal political party, it was like noticing a well by day and falling into it at night.”

Perceiving the status of the Dalits in Hinduism, and the discriminations practised against them, the thought came to Lakshman’s mind to convert to other religion. He paid visits to their respective religious places and read their texts. But he found that in all religions people suffer from the same indignities and differences. “No one is concerned about the poor and underprivileged people. This made me lose fascination for any religion.”

After leaving the Samiti, Lakshman joined the Karnataka Vimochana Ranga, whose members work for the Dalits and only eat if they are given something, otherwise going hungry. Later, Lakshman and other like-minded people started the Jaathi Vinashaka Vedhike, a forum for the eradication of caste.

A discussion is missing in Lakshman’s biography of the impact of political Hindutva on the Dalits. This is especially needed because there has been a gradual rise of saffron power in Karnataka, which would not have been possible without support from people belonging to all communities, including Dalits. The biography is nevertheless an excellent read to understand the Dalit’s predicament in Karnataka.

Unfortunately, Lakshman died before the English translation was published. May his soul rest in peace.

Samboli! Beware by Lakshman (translated from Kannada by Susheela Punitha) is published by Niyogi Books, 2018.