'Today Starts the Struggle, Let Us Ensure There is a Tomorrow'

Debiprasad Chattopadhyay, Philosopher and Humanist

In the hustle and bustle of daily news reporting one tends to forget personalities who not only gave a new edge to their profession, but were geniuses with a sweeping canvas. One such who comes immediately to mind is the renowned philosopher Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya, who would have turned a hundred years old on November 19.

While Debiprasad centenary celebrations have finally kicked off in Kolkata, Delhi city of his birth, dot on time, the capital of India which years ago saw him honoured many times, seems to have been caught in its cocoon of political masala.

The international philosopher Debida – with whom one had a personal acquaintance, as a journalist and as a brother in law, sharing many moments – would always take on superstitious beliefs, myths, and unscientific mumbo jumbo. He had almost unending discourses on his favourite themes, like what is living and what is dead in Indian philosophy, his earth shaking Lokayata, his branching from philosophy to the history of science, and his attempts to bond science and philosophy.

In fact his work Science and Society (1977) exhibits an uncompromising attitude to the forces of reaction, which is anti-science and promotes faith in premises unproven by observation and experiment.

He showed how the authors of the Dharmashastras (religious law books) advocated cow worship while medical texts recommended the flesh of the cow and of many other quadrupeds in their dietetics.

It is, however, also true that the medical texts at the same time speak of devotion to the cow, the brahmanas, the gods, etc.

Instead of leaving matters as they are, Chattopadhyaya boldly put forward a theory of ransom, a kind of appeasement offered by scientists to the power that be, so they could continue their work in their respective fields of astronomy, medicine and so on.

Debida came from a very illustrious family of undivided Bengal. His father Basantakumar Chattopadhyaya was a highly respected personality in the Indian bureaucracy. Like him both his sons, Debiprasad and Kamakshiprasad, were gold medalists from the University of Calcutta.

Basanta Kumar was a staunch Hindu and a nationalist. As the story goes he would shake hands with British officers in his office and then purify his hand by washing it in a bowl of Gangajal.

At the same time he was a thorough humanist, and as his granddaughter Aditi recalls, at the time of Hindu-Muslim riots in Calcutta he gave shelter to a Muslim fruit seller family in his own home.

Basanta Kumar, a great Vedanta scholar, was often at ideological loggerheads with his son Debiprasad. Aditi mentions in her speech at Nandan, Kolkata that when this ideological fight would take place between father and son, the children would carry small pieces of paper between the second and the third floor with arguments jotted down. The two however had a great relationship of mutual respect, thunderstorms notwithstanding.

Debibiprasad was taught by the illustrious philosophers Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan and Surendranath Dasgupta, stalwarts of traditional Indian philosophy, but he produced a thesis on an absolutely different aspect of Indian philosophy: lokayata, Indian materialism as against spiritualism.

Once he told me jocularly that he had sold both his gold medals for a big bash. In fact both he and his friend and mentor Samar Sen sold their gold medals (Sen got it for standing first in English literature in B.A.) to get their books of poems published, as they did not want to ask their parents to finance their venture. The leftover money was however spent on food and drinks. This shows their unique apathy to awards.

His first book of poems was also his last. But his talent in writing for children was almost unparalleled. The children's magazine Rangmashal, which he edited along with his brother Kamakshiprasad, was very popular. Apart from hilarious short stories which enchanted young readers, he wrote a number of books on science in simple language to bring science close to children, in Janbar Katha (Book of Knowledge), Satyer Sandhane (In Search of Truth), Se Juger Mayera Baro (Those Days Mothers Were Superior) etc.

Ironically Debida is not remembered as he should be countrywide – even in his centenary year, when he is most relevant, in view of the fact that the country is seeing almost a do or die battle between the forces of secularism and the scientific temper, on one hand, and on the other an assortment of ‘Godmen’, forces of Hindutva and right reaction striving to take India back to the dark ages.

It is equally true, however, that initiatives have begun in some states, with Karnataka taking the lead, followed by Andhra and West Bengal.

On November 19 the city of Kolkata had two major celebratory functions, one at the Asiatic Society and the other at the cultural hub of Kolkata Nandan. The Asiatic Society organised a two day seminar-workshop in collaboration with the All India People's Science Network (AIPSN) on ”The Contribution of Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya in Understanding Science and Society in Ancient India”. The keynote address was given by the noted scholar Ramkrishna Bhattacharya. The other speakers included P. Rajamanikkayam, general secretary of the AIPSN, Arunava Misra, Satyabrata Chakrabarty, the general secretary and Isha Mahammad the president of the Asiatic Society.

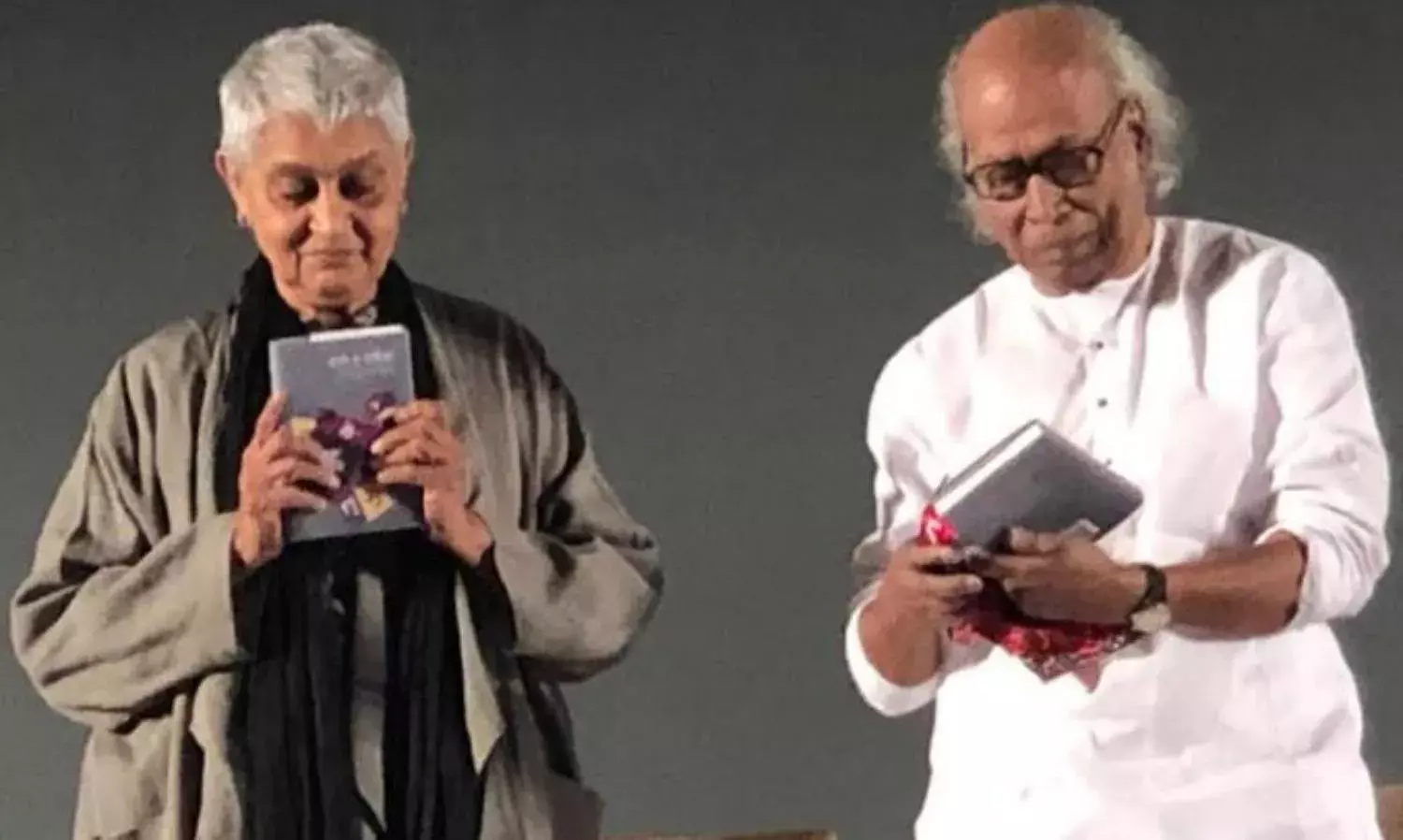

Anushtup Publications organised a seminar at Nandan, in the evening. A special issue is expected shortly on DP as he was known. The speakers included noted scholar and feminist writer Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, professor of the humanities at Columbia University, and Shankha Ghosh, perhaps the seniormost poet today in Bengal, highly respected for his poems and his fearless criticism of what is wrong in the contemporary political arena. Debiprasad's daughter Aditi Chatterjee presented her personal reminiscences.

When one would get articles from him as a journalist one felt he could write on almost any subject, with a polish that could put many journalists, philosophers, sociologists and even lovers of scientific temper to shame. Here indeed was a versatile all rounder, who besides being a specialist in philosophy and the history of science could dabble in lighter literary pursuits as well.

Debiprasad will always be known all over the world as the explicator of materialist philosophy in India, and for his creative contributions to Marxism. His magnum opus is indeed Lok?yata (1959), as his friend and scholar Ramkrishna Bhattacharya opines.

His house in SN Pandit Street was a sea of books, virtually acting as the walls. They were both in Bengali and in English.

As he told me once: “Today starts the struggle, let us above all ensure ourselves that there is actually a tomorrow.”

He was referring then to Roop Kanwar. Sadly the situation has not changed much today. Look at what is happening in Sabarimala. In the name of tradition regressive practices are often continued and are specially whipped up, in election times as today.

In EMS Namboodiripad’s view, expressed just after Debiprasad’s death in 1993, “Chattopadhyaya’s works provide a sharp weapon against all this revivalism and obscurantism.”

S.K.Pande is a veteran journalist.