'Back in our Homes, Each Madhubani Painting is a Family Endeavour'

No two Madhubani paintings are the same, such is the diversity

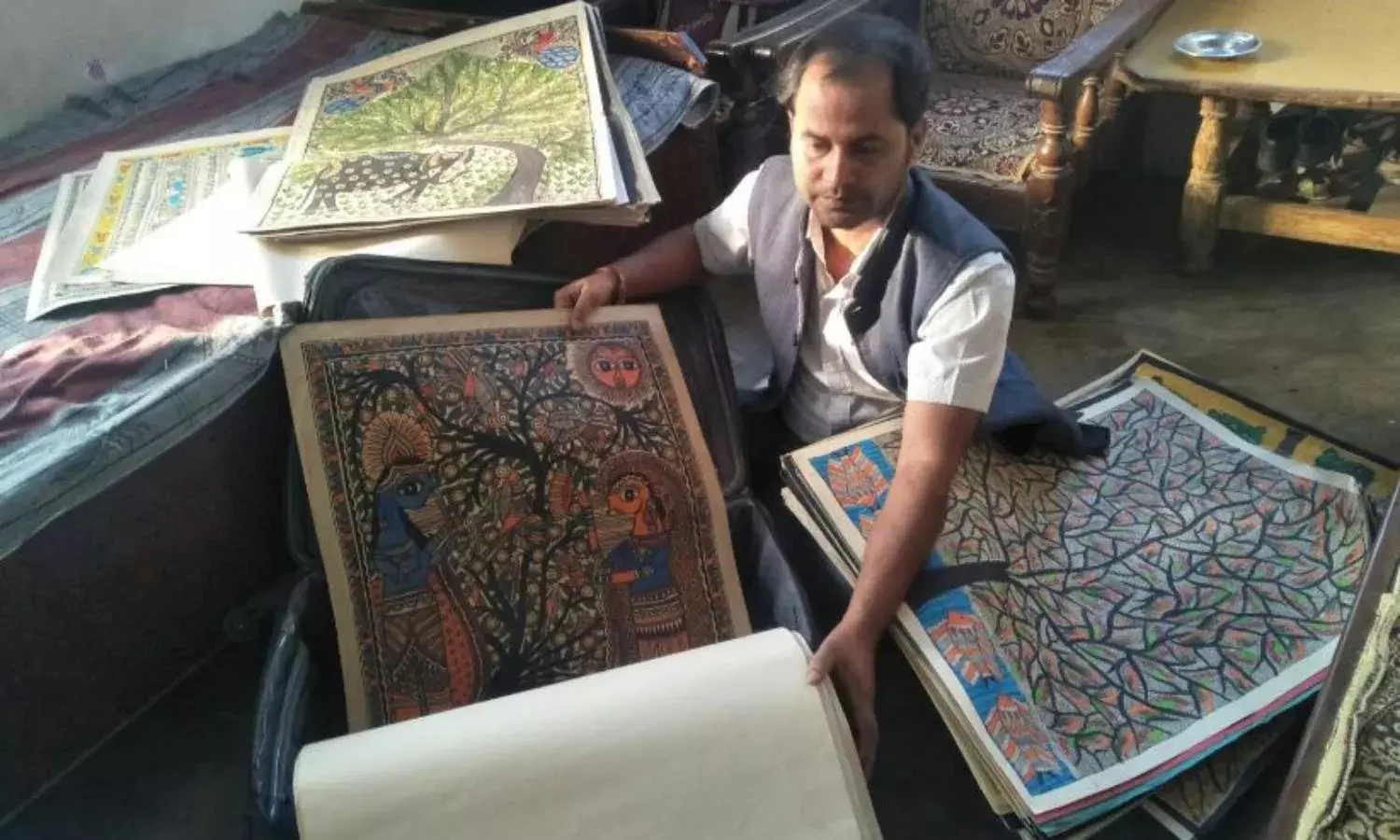

As Saroj Kumar Jha, 32, opens up his heavy suitcase containing more than 500 Madhubani paintings created in the past 25 years by him, time literally pauses.

Every single piece, often the tenuous result of many days’ work, tantalises.

Madhubani painting is a form of folk art that emerged at least 150 years ago in Bihar. Its roots lie in the painting of mud houses in the villages, often during weddings and religious rituals. In the 1960s, it is believed, then PM Indira Gandhi sent her aide Bhaskar Kulkarni to inspect and promote this traditional painting style.

But the journey undertaken by several Madhubani painters in the capital, like Jha, reveals an interesting update.

As he carefully opens up the folded handmade papers with captivating figures of birds, fish, Gods, elephants and flowers, Jha delves into his past. ‘I started Madhubani when I was twelve. Back in our homes, each painting is a family endeavour. I learnt the basics of it from my mother and grandmother. Apart from selling my paintings at Dilli Haat and doing projects with the Bihar government, I also conduct workshops at the Asian College of Journalism (Chennai) and other institutes,’ he says.

‘Every Madhubani painting has some common themes. First, the one-sided face painting of folk art, typically called Mithila painting. Second, the other form includes very fine line-painting, often done using nibs and without colour. The third variety is called Godna painting, which is often also tattooed on the body. This form of Madhubani painting was invented by the lower castes in Bihar,’ he says.

Jha’s face lights up as he talks about his new experiment. ‘In my new work, I am trying to create a vertical pattern of Ardhanareshwar (Half-Shiva and Half-Parvati).’

He explains how artists use turmeric and dry cowdung to dull out the handmade paper. The texture of the base color is also an essential part of Madhubani art.

Initially, natural colours like turmeric, flowers, and peepal tree bark were used for Madhubani painting. Unfortunately, their shelf life was only one day, and they degraded easily. The earlier nibs were made of bamboo.

Over the years, as acrylic colours have become affordable, several Madhubani painters have shifted their choice. Often acrylic colours are used for better gloss and shine, a difference that the careful observer will notice.

Jha also explains the meaning behind the community activity of creating Madhubani paintings. ‘Every single symbol has a value. For example, a tree denotes long life, birds stand for happiness, elephant is a symbol of power, fish denotes good luck and peacock is a sign of love,’ he reveals.

When asked if he plans out a painting before he begins, Saroj says, ‘It is a very intuitive process. One can’t think before. We start by completely colouring the base and then proceed accordingly. No two Madhubani paintings are the same, such is the diversity.’

Explaining how the Ministry of Textiles has helped Madhubani painters, he explains the process involved in getting tenders for various projects, which are open to artists all over India. The National Handicrafts and Handlooms Museum is another exhibition space.

Even private companies like Peter England have engaged with artists in making bespoke collars for their apparel designs. Ventures like the Aamby Valley City in Lonavala contractually employed Madhubani artists to design walls under the inspection of Subrata Roy, chairman of the Sahara Group.

And Jha himself has been part of the effort to promote this traditional art form: trains like Rajdhani as well as Sampark Kranti Express have been adorned by this folk art, both inside and out.

Turning towards the grim realities that affect Madhubani artists, Saroj says that ‘it is not a stable income option; it depends completely on the business. For 15 days we are allowed to set up stalls at Dilli Haat, which costs around Rs 11,000. The days we don’t sell, it’s difficult to put food on the table.’

What about the impact of foreign tourism in the Mithila region? Jha explains: ‘Yes, now we artists have more visibility. But it has also created stiff competition. Poverty has definitely reduced, but we artists who have migrated to Delhi often have to compromise on the rates at which we sell. For example, if a canvas took more than 15 days to be painted, it’s quite rare that every customer will understand the finesse of it. Thus, bargaining has increased, tremendously.’

He further explains that a 10-hour painting amounts to only Rs 1000, a price customers will often haggle down. Due to the rising competition, artists will sell it for Rs 600, otherwise there won’t be food on the table that day.

The difficulty of selling Madhubani paintings at a dignified price is thus taking its toll.

As more and more artists like Jha migrate to cities, they face tough subsistence choices every day. ‘I would like my daughter to learn from school and education to choose a different field than me,’ he says.

As Jha starts folding the canvases back into his briefcase while looking at his two sisters and wife with humble pride in creating these masterpieces, he knows how treacherous the process of recognition has been. A true artist who will create till his last breath, Saroj Kumar Jha is an inspiration to his community back home.

Every day is new, with its own trajectories, and so is every canvas he creates.