'No Fathers in Kashmir' Struggles for Censor Certificate: Is the CBFC a Cinematic Ass?

CBFC continues to give grief to independent filmmakers

On January 13 2016, filmmaker Pankaj Bhutalia had said “The CBFC is an overrated and stupid institution, it has outlived its purpose”. Bhutalia at the time had just emerged victorious of his court battle with then Pahlaj Nihalani led CBFC for the adult certification of his Kashmir based film ‘Textures of Loss’.

Three years and a change of chairman later, another independent filmmaker with another story on Kashmir evoke the same struggle.

As I speak to Ashvin Kumar about his film No Fathers in Kashmir, he realizes that today marks the six-month anniversary of his struggle with the CBFC.

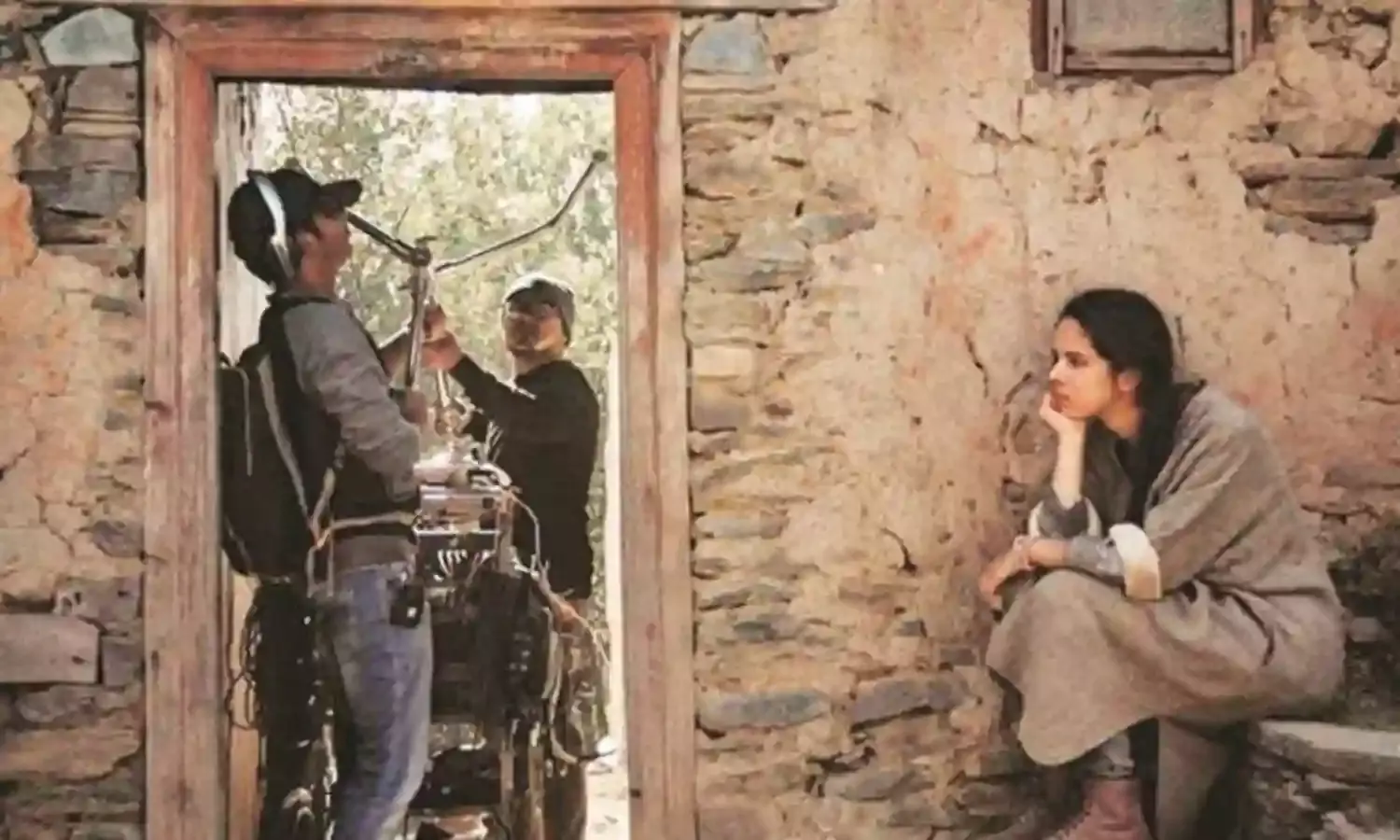

On July 16 2018, Kumar submitted his film to the Board only to get a series of unsolicited cuts and a conditional A certificate. A look at the plot makes it an easy guess on what triggered the reaction. Set in the Kashmir Valley, the film follows British Kashmiri teenager Noor who returns to look for her long disappeared father and is aided by local youngster Majid who has had a similar fate.

However, the adult certification limits the reach of the film and ironically leaves out the young adult demographic that the film is based on.

The director has appealed to the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT) which mandated the Board to give the film a proper hearing and also wrote an open letter to Chairperson Prasoon Joshi.

Talking about the CBFC, Kumar says “it’s a colonial institution with no place in a democracy. It is most conservative and has no connection with the law of the land.”

He also points to some grave functional irregularities saying that the Board’s only role is to provide certification and not censorship. Currently stuck in what he calls “a hockey match between the CBFC and the FCAT”, Kumar asks why there isn’t a lawyer on the Board.

The Oscar nominated filmmaker is the latest addition to the tribe of film personalities once hopeful but now disappointed in Prasoon Joshi’s management of affairs. He says “I am not referring to any political intentions but it’s difficult to give the board any benefit of doubt.”

His last two films ‘Inshallah Football’ and ‘Inshallah Kashmir’ were both based in the Valley. I ask about this patterned interest and am told “Kashmir intrigues me, it is 20 years ahead of us in what happens when the government impinges on the personal lives of its citizens.”

Interestingly, both these films went through the same censorship tussle with the CBFC only to win National Awards the same year. Things seem to be more difficult this time as the CBFC deadlock has made the director miss the National Awards deadline.

In times when box office releases are having to compete with online platforms like Netflix , Kumar doesn’t wish to simply resort to the latter. He says he wants “all media channels” and rightfully so.

In a rare sighting, mainstream Bollywood A listers like Swara Bhaskar and Alia Bhatt have also come out in support of the film. As we talk, news breaks over Twitter and I ask Kumar what his advise is for other independent filmmakers wary of the same struggle, he smiles and says “ You’re seeing me fight one”.

But the struggles of Ashvin Kumar and Pankaj Bhutalia are anything but that of the misunderstood rebellious Byronic artists. They point to the shrinking space for a filmmaker’s freedom of speech, the archaic yardstick of certification that the Board continues to employ and its tyrannical and almost secretive functioning.

Kumar claims that his film has "no sex, no violence, no vulgarity, no nudity, no drug abuse" and yet has been handed an ‘A’.

Film critic Shoma Chaterji explains “The "A" certificate technically means "for adult viewing only" for films that have (Restricted to adults) - Strong intimate scenes, abusive language that’s why the window covers only adults. However, this particular segment has become very outdated considering that the rapid progress in the information highway has rendered it almost completely redundant. Children today have almost free access to intimate scenes, themselves use abusive language and are openly aggressive in behaviour so an A has become a laughable reality today across the child and juvenile population. Besides, this "A" has been seen to have been given not necessarily sticking to the norms laid down by the CBFC. There have been political and other reasons for granting or not granting an A to this or that film.”

The ‘No Fathers in Kashmir’ fiasco has also brought to forefront the callousness with which the Board deals with independent films and their certification struggles. On 23rd January 2019, a day after Kumar’s second FCAT hearing, Board member Vivek Agnihotri called news about the film not being passed a rumour and tweeted that he had cleared the film “a long time ago” with an A certificate.

The impunity of the lie was not lost on the director who responded by uploading the Board’s official document that stated the film could be given an ‘A’ “provided” the excisions are carried out. ( LINK HERE : https://t.co/dCB2wBAySK (ashvinkumar/status)

Actor Anshuman Jha also tweeted Agnihotri’s “advice” to him during the recent five hour long FCAT hearing : “make the suggested cuts or else go to the courts” . He asks if the film has been cleared, then why the advice.

As the hashtag LiftTheBan circles twitter for what has now turned into a long-drawn controversy, Shoma Chatterji’s questions come to mind: “Is the CBFC a cinematic ass? Or, is it a political one? Or is it a sandbag and a whipping boy of filmmakers across the country with nominal powers that are taken away by the politicians in power whenever they feel like it?”