AJJI – A Film That Attacks A Diseased System

Can a person truly stand on judgement?

Ajji is a shocking film. Through an ideal marriage between form and content, equipped with the infrastructural back-up of cinematography, editing, sound effects, music and acting, the tapestry of Ajji is enriched in a story devoid of glamour, chutzpah, romance and everything expected from a film, Devashish Makhija’s second feature film Ajji comes like a virtual slap on your complacent face. A face that belongs to all of us who cluck our tongues sadly when we watch candlelight marches on our television screens demanding justice for a rape victim and forget all about it once the news channel turns to another report on the inhumanity of man against man.

The film produced by Yoodle Films, was screened at the Indian Film Festival at Los Angeles where actress Sushama Deshpande who played the title role, received a Special Jury mention for her performance in the film and also The Flame Award at the UK Asian Film Festival. The film also won the Fresh Blood competition at the Beune International Thriller Festival, 2018. Among other marks of recognition and festival screenings are – official selection at the 2017 Busan International Film Festival, showcasing in the New Currents Section of the 22nd Korean Film Extravaganza and nomination for the Oxfam Best Film on Gender Equality Award category at the Jio MAMI 19th Mumbai Film Festival with Star 2017.

Ajji means “granny” in Marathi. Ajji, around 65, is grandmother to ten-year-old girl, Manda, who fails to return from Ajji’s customer’s house where she had gone to deliver some tailored clothes. When Ajji along with Manda’s parents go looking for her in the pitch dark of night, they chance upon her battered and bruised body lying in a ditch. Manda has been been brutalised, bashed up and raped and cannot even speak let alone rise from her bed. She continues to bleed round the clock and afraid of summoning a doctor is tendered to by indigenous ointments bought from a local woman.

Ajji is a very poor woman who lives in a shanty in a slum with her son, she does not communicate with, his wife and the granddaughter Manda. When the local cop comes to ‘investigate’ it is more to warn them against filing a FIR that may place them in trouble because they are involved in ‘illegal’ trade and more importantly, because the rapist Dhawale is the son of the powerful local councillor. Manda’s parents are terrified and refuse to file an FIR against Dhawle as they fear repercussions.

The policeman, visibly relieved, leaves the scene and is angry when Ajji tells him to write down the complaint and file a FIR. Ajji is as if, stunned by an electric shock worse than the debris of her life. The rapist is known, specially for raping minors, construction workers on the site where his constructions go on, and Dalit women but is never punished thanks to the greedy policeman who is treated like a slave by Dhawle. We know the victim whose pain does not seem to dissipate at all and yet, we, along with the characters in the film, can do nothing but watch helplessly.

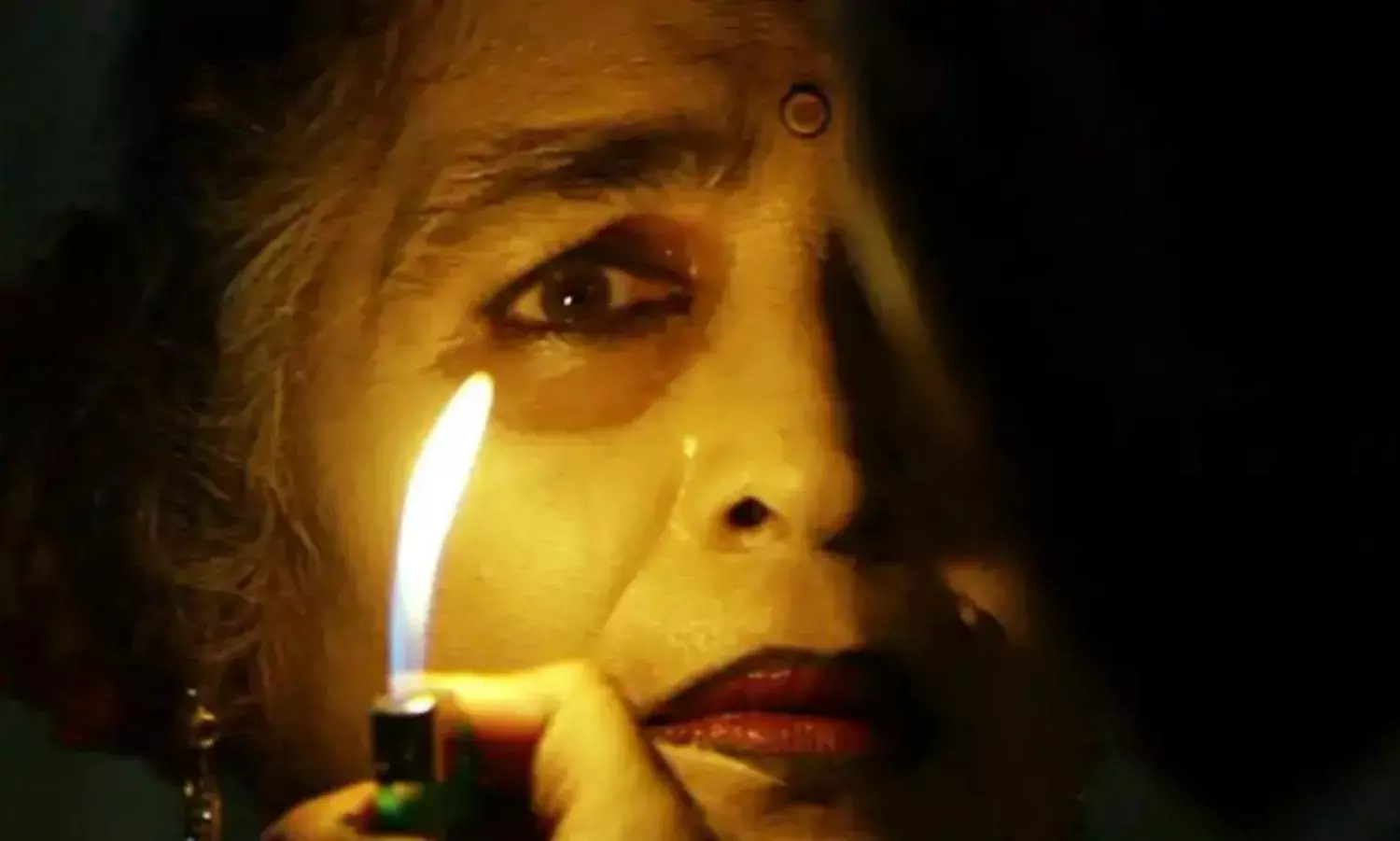

Rape in Indian cinema is used mainly as a technologically skilled manipulation of male visual pleasure created with imagination, for purely commercial purposes. But Devashish Makhija, the director of Ajji staunchly refuses to create the space for visual pleasure because the actual rape is never shown. It is the impact of rape, mainly on the little girl who innocently asks her granny whether she has finally grown up or not, and the granny that becomes the focus of the camera, the sound design and the narrative. The magic lighting alternating between dark and brightness on her face show her firm anger and incredulity more than the deep lines on her aged face.

Held in tight close-ups and medium close-ups, her face is filled with myriad expressions that reveal her anger at herself for not being able to help Manda, anger at the police for its corruption and sycophancy, anger at her own son and daughter-in-law for not seeking medical help for their bruised and abused little daughter and anger at Dhawle she begins to spy on in the darkness of night when everyone at home is fast asleep.

Ajji visits the local butcher who is her friend though her family is vegetarian. Her demand is scary. “Teach me to butcher cows and cut them into beef and sheep to slice and turn into meat,” she tells him, He says that Muslim women are not allowed to do this so how can a Hindu woman learn the skill of butchering? But the old lady is adamant and says she will not budge from his shop unless he teaches her what she wants him to. So, within her daily chores of applying ointment to Manda’s painful sores, working on her tailoring assignments and spying on Dhawle in the middle of the night, Ajji begins earnestly to learn the fine skill of butchery swallowing her disgust and not permitting to be overpowered by it. .

Ajji (Sushama Deshjpande) converts her aim of destroying the rapist into a learning experience she may never have imagined in her entire life. The most outstanding feature of her character is her tremendous courage, unfettered by her terrible arthritis, her age, her poverty, her mental stress for her grand-daughter’s condition. She braces and preps herself carefully and cautiously to strategise her plan of action. From her clandestine espionage, the audience also peeps into the bizarre ugliness of Dhawle’s perversion especially in a scene where he is slowly brutalising a mannequin and dismembering it cruelly, severing her limbs one by one as his way of enjoying sex till, at the end of the act, the camera focusses for a minute on the severed head of the mannequin staring blankly into space. This scene is as bizarre as it is extremely scary and may also be read as a vicarious projection of a real woman being slowly dismembered.

Dark goggles, a mandatory wear by both Dhawle and his father, are used as symbols of power, of their subconscious way of hiding their crimes with the darkness that the glares provide and also, probably invest them with some amount of anonymity they can use for their own protection as and when. The performances appear as they organically flow out of the actors, every single one of them, led by Ajji and the main perpetrator Dhawle. The art direction taking in the shanty with its blue walls, a family picture, vessels, a small cooking place and Ajji’s sewing machine, including the dull and overused dresses they wear, are minutely detailed. That touch of Ajji feeding the street dogs with the meat she cuts on the first day, as also when Leela paints Ajji’s face with thick make-up are truly moving.

The fragmentation and fabrication of the female body, the play of skin and make-up, nudity and dress, the constant recombination of organs as equivalent terms of a combinatory are but the repetition, inside the erotic scene, of the operations and techniques of the apparatus : fragmentation of the scene by camera movements, construction of the representational space by depth of field, deffraction of light, and colour effects - in short, the process of fabrication of the film from decoupage to montage.

This is a scene that takes a longer time than it ought to have, that invests the film with perverse voyeurism it could have and should have done without. True that it highlights the primal nature of Dhawle but it also vicariously plays upon the defragmented body of a woman, here, represented in the form and shape of a mannequin. The camera plays around with the love-making focussing on the mannequin’s parts of the body till the dismembering begins – the disrobing, followed by the stripping, pulling the hair off the head revealing the skull, pulling off the legs one by one, so also the arms, the torso and the breasts, slowly till the head remains.

Except for this torturous scene, not once does Makhija use rape as a political strategy to provoke audience voyeurism. Manda cringing in endless pain, trying to get close to her father for some consolation, highlights the tragedy of being poor, vulnerable and helpless in the face of a criminal who continues with the power he derives from his evil father because the system is corrupt and is more than willing to look the other way in exchange of money and other favours.

There is no attempt to sensationalise the drama, or, any melodramatic touches of chest-beating or wailing or crying when the girl is brought home which is also a powerful metaphor for the silence these marginal people have turned into a way of life to protect themselves from further humiliation, insult and torture.

Leela (Sadiya Siddique) secretly helps Ajji in some of her endeavours and throws up an interesting cameo. She is a prostitute pregnant at the present time and does not seem to have a clue of what Ajji is contemplating and why which the audience is also not privy to. She is their neighbour and tries to nurse back a fellow sex worker to health who has been a victim of brutal attack by Dhawle because she refused to commit to his demand for sex.

The climactic scene with a drunken Dhawala tottering down the lonely and dark alleyways, with Ajji following him, turns the tables on the diabolic Dhawle. He does not even know that he is being stalked with a purpose by someone much weaker than he is in every way - physically weak, chronologically old, and a woman at that who one cannot even imagine to be the perpetrator of a murder. Can and does this justify Ajji’s well-planned, calculating and diabolic revenge plan? Or does this place her on the same platform that Dhawle stands on?

This raises several questions of right and wrong, what is morally justified and what is not. But when the system in which Ajji, her son out of a job for an accident in the workplace, Manda and Leela live in is corrupt, corroded and diseased, with the law, the administrative and the judicial machinery even at the slum level are completely compromised, can one truly stand on judgement on the wronged woman like Ajji?

Every man, woman and child is capable of anything he/she puts her mind to, never mind the lines that divide us in terms of age, education, health, place, language, financial status and class. This is the basic foundation on which the script of Ajji is built.

The basic philosophy is not only the attack on corruption, crime and power but also sheds light on the way these three socio-political evils, personified in Dhawle, are manipulated to pay the price for their evil deeds through the same device that marks them as evil in the first place.