Why YS Parmar Remains a Legend, Given Most Present Day Politicians

It was Parmar's differences with Sanjay Gandhi that led to his resignation

SOLAN: One thing that’s most difficult to find in the top political leadership across India is simplicity and absolute commitment to the masses. It’s difficult to imagine that there once existed such leaders in independent India, who have now been consigned to oblivion. Leaders of stature who were dumped by their own parties, the same parties that are now paying a heavy price.

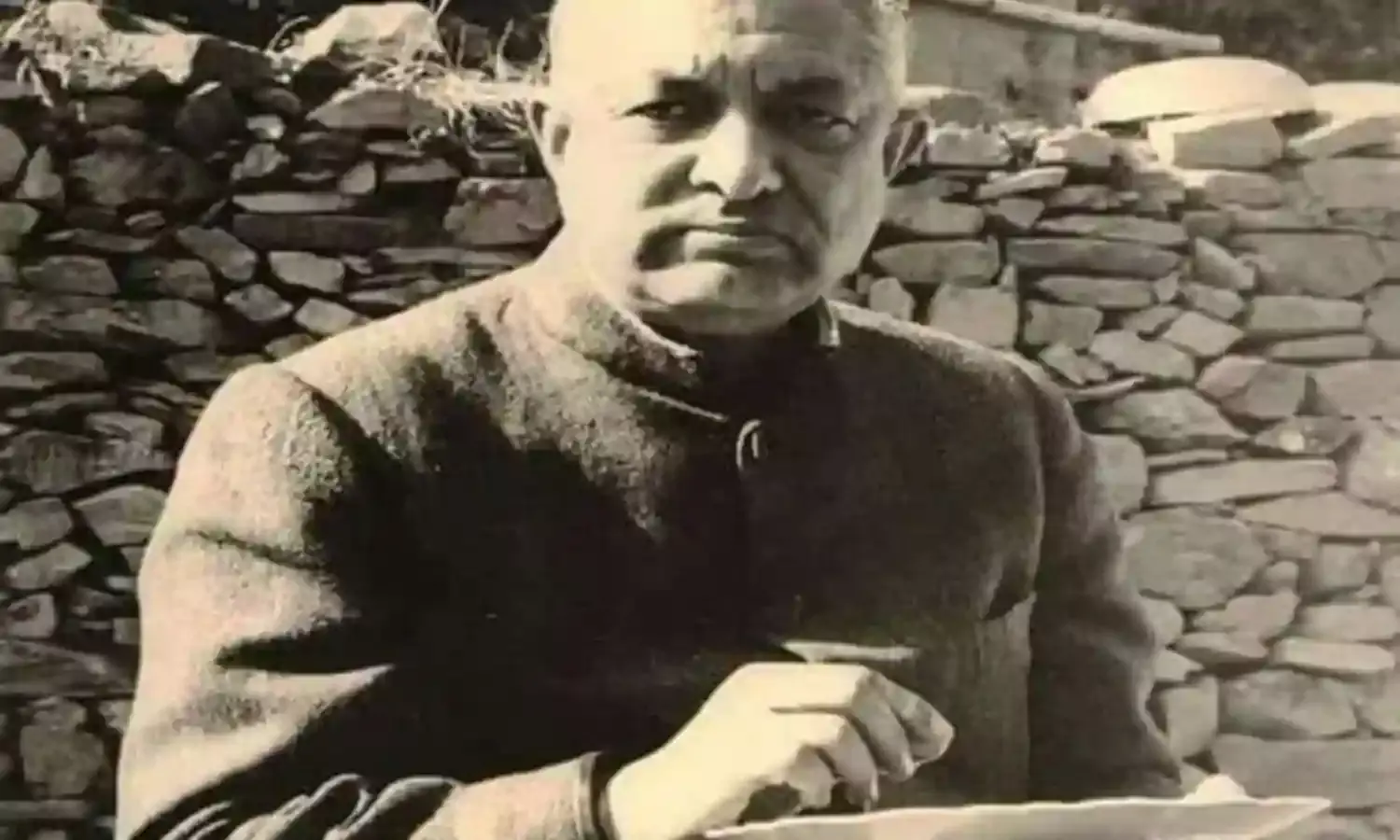

One such name is that of Dr Yashwant Singh Parmar, the ‘Legend of Himachal Pradesh’. Come to think of it, there’s very little information about him in the public domain, despite the fact that he was the first chief minister from the Congress in the hill state, and the only one from Himachal to have served consecutive terms. His towering personality still lives in the hearts of the older generation, his contemporaries, who do not tire of talking about his impeccable public conduct, sincerity, honesty and commitment to the public cause.

A few pointers are enough to measure the present lot of politicians against those like Parmar. Can you imagine a chief minister quietly retiring from public life after resigning from his post? Or retiring with a three-digit bank balance? A chief minister who worked to develop all the constituencies in his state barring his own?

Born in Chanhalag village of Sirmaur district on August 4, 1906, Parmar earned a doctorate from Lucknow University. He worked in the judicial services for a while, and in 1946 went on to become a member of the Constituent Assembly of India. He was chief minister in the Himachal government from 1952 to 1956, stepping down when the state became a union territory administered by a Lieutenant Governor. He was chief minister again from 1963 to 1977 during which period Punjab was partitioned, and Haryana and Himachal became full fledged states.

It was Parmar’s differences with Sanjay Gandhi that led to his resignation and return to his roots in Baghthan in 1977.

“He was a leader held in very high esteem by both Pandit Jawahar Lal Nehru and Indira Gandhi during their tenures as prime minister. He believed in simplicity, and his philosophy was that capital should flow from the urban areas to the villages,” says Tulsi Ram Chauhan, who was Parmar’s close confidante for more than three decades, and still retains dozens of letters written by Parmar to him, which give a close understanding of the kind of person he was.

“Can you even imagine anyone contesting elections today without spending a rupee? He was the one who did so. In the 1967 polls, the Congress party gave Rs 4,000 to him for campaigning. He told me to distribute it among the party’s other candidates, refusing to take even a rupee. He never allowed us to make use of government guest houses, asking us to stay among people in the villages when we were out. He never entered the premises of any industrialist or businessman and discouraged us from doing so,” Chauhan told The Citizen.

He related another anecdote. “At one point I angrily wrote to him saying that he was not working to address the concerns of the people of Renuka. He wrote back apologising and promised to make financial provisions in the next budget for the issues raised.”

Chauhan shared a letter written by Parmar to his partymen after his second marriage with Satyawati Dang, following the demise of his first wife Chandrawati. “As an absolutely personal matter it need not have been mentioned at all. But members of the party are like members of a family and so it is good both to talk to them and also to confide in them, hence this letter.” It shares the circumstances in which he remarried. Such openness with party comrades is simply unknown these days.

There are many tales about Parmar’s manner in public life. “He always believed in building roads as the lifeline of the new state. He would trek through the villages along with officials and porters carrying a typewriter so that orders could be typed and signed on the spot.

“When he visited the villages, residents would volunteer to make a path to the next village which he would visit. He would eat the local staple with them, sitting with them on the ground. Whenever possible he would also shake a leg, dancing especially the nati folk dance which he performed very well. I remember having seen him perform a nati and eat lushke (a local delicacy) in my village,” a resident from a village near Haripurdhar told this reporter some time ago.

People also recall how Parmar got his ancestral property auctioned off, to repay the loans his father had taken to get him educated.

To see the aura of Parmar the best place to visit is a photo exhibition at the Dr YS Parmar University of Horticulture and Forestry in Solan district. People in his native district of Sirmaur can often be heard complaining, “He tried to develop all the other districts while Sirmaur suffered and till date remains the most backward district. He would tell us that Sirmaur is the district that has to always give and never take.”

Another reported fact is that at the time of his death on May 2, 1981 his bank balance was a mere 563 rupees and 30 paise.

“He was a person who worked on a three dimensional theory for developing the state. I remember that the 40 kilometre Solan–Rajgarh road was built through shramdaan (voluntary labour) in which he had also participated. The same model was applied elsewhere also,” recalls Kul Rakesh Pant, former chairman of the Solan Municipal Council.

Old timers say Parmar was never on good terms with Sanjay Gandhi, who was known for his brash and arrogant functioning in the Congress. “The trigger came in Kasauli, where Sanjay arrived and took off his footwear without bothering to put it in the proper place. Later, upon not finding his slippers he created a scene, to which Parmar told him to his face that he should have kept them aside properly.

“After resigning Parmar never bothered to talk about the episode, simply saying he did not want to join issue with children. He just came back to Baghthan,” says Chauhan.

Engineers in the state still recall how letters would be sent from Parmar’s office to top engineering colleges like the Roorkee Engineering College (now an Indian Institute of Technology) to send their best men to Himachal for recruitment in the state services.

Since the state comprised the hill districts together with a large area carved out of Punjab, Parmar always wanted his state to perform better than Punjab, which was then among the best developed states in India. The seeds he sowed have borne fruit, with Himachal doing far better than several states of the country on several human development indicators like food distribution, healthcare, and primary education.

YS Parmar set an example in Indian politics that very few can emulate. Former Bharatiya Janata Party chief minister Shanta Kumar recently said, “Being in the opposition I was among his biggest critics on issues of governance when the assembly was on. But the debate was always in civilised language, and I was the first to congratulate him when the budget was presented.

“Both of us were of the opinion that the government and opposition need to work together, and this has remained a tradition in Himachal.”