What I Saw Covering the 1984 Anti-Sikh Pogrom: Nightmares Still Haunt Me

I saw some 50 vultures catch hold of a man

It was a shivering December evening. The year was 1988. After submitting my resignation letter to the news agency I had served for 10 years, I was entering the Press Club of India located on Raisina Road in New Delhi.

Occupying a seat inside, I waited for some fellow journalist friends to come. I was engrossed in thinking how to handle the political beat I was shortly to be given by an English daily.

A few feet from me, a “clean shaven” man sat in a chair. He watched me for a little while, then came up to me to ask, how are you doing? “I am doing well, but I don’t recognise you!” I said.

The reply he gave created a storm in my mind that continues to rage even after 35 years.

Addressing me by my name, he said “You cannot recognise me in my present look, but when I was a sardar (a Sikh) you were my very good friend.”

“Why aren’t you a sardar any more?” I asked him involuntarily and his reply was, “You never allowed me to remain one.”

I asked him his name and he told me. I immediately sprang up from my seat to embrace him. He was a news editor of a Gurmukhi daily published from New Delhi. We would often cover events together and even go to Connaught Place to eat at Kake Da Hotel.

My mind went back to Patna, October 31, 1984. Taking seven’ days leave from the news agency I had gone to my in-laws’ place in Patna. Late that night I was to catch a train to New Delhi.

It was half past midnight when I jumped out of a rickshaw to come to say goodbye to my colleagues at the Patna office. Our office was located on Frazer Road.

Travelling slowly from Jakkanpur where my in-laws lived, I had found the roads unusually empty, with clusters of people talking in subdued voices.

At the office the chief of the news bureau said he had just received a teleprinter message that I should stay for a day or two as an “extra hand” in the Patna office to give more inputs to the “developing story”.

“Don’t you know Madam is dead?”

He was referring to prime minister Indira Gandhi. His words shocked me. However, more shocks were in waiting.

Fraser Road Chowk, Patna. The time was around 3.45 pm. I saw the owner of a very famous eatery pulling down the shutters. At that very moment, some 30 or maybe 40 persons attacked him.

I knew him very well as we reporters usually thronged there. The mob was beating him mercilessly. He fell on the concrete pavement outside his shop, bleeding. I never met him again.

The Kotwali Police Station was no more than 10 minutes’ walk from there. No policeman came.

I never wanted to remember the anti-Sikh riot that I covered. But since 1985 it keeps rising like a phoenix from the ashes of human shame. I kept mum. This time, it has resurfaced with certain political quarters saying it could have been avoided, and rival political quarters working overtime to cash in on it.

Really in India, politicians can even play politics out of the kafan (shroud) of riot victims. No matter who they are: Sikhs, Hindus, Christians or Muslims.

Around 5.30 pm I left the office to file some firsthand stories for my agency. The first story was the last thing I ever wanted to see.

As a reporter, I have covered many riots including those in Kanpur, Bhopal and the riots that followed the demolition of the Babri Masjid. But nothing I have seen compares with the 1984 riot in terms of brutality.

As I walked up to the Frazer Road crossing, I saw some 50 vultures catch hold of a man and make him stand on the traffic island. They were cropping his hair and beard. After that, they started beating him most brutally.

Trust me, he was not even crying or shouting in pain, but feebly groaning.

“Why are you standing here? I can’t save you if something happens. Go away, go away Bangali Dada.” He warned me not to mention his name in my report.

He warned me sternly as he was leading the mob. I had known that Member of the Legislative Assembly since he was a chhutbhaiya neta, an ordinary political worker.

The Kotwali Police Station was a five minute walk from there. But no policeman came.

It was only on November 2, 1984 that the army was mobilised in the nine worst affected cities, with orders to shoot the rioters. Patna was one of them. Other towns were Delhi, Indore, Rae Bareli, Kanpur and Dehra Dun. Curfew was imposed in 30 cities.

Officially, 24 people were killed in Bihar as well by that time. We do not know the “unofficial” number of casualties.

A month ago on November 12 a play called Jalta Hua Rath (Burning Chariot) was staged in Lucknow. I was in town but missed the play, which is based on a story written by Swadesh Deepak. I don’t refer to it for nothing.

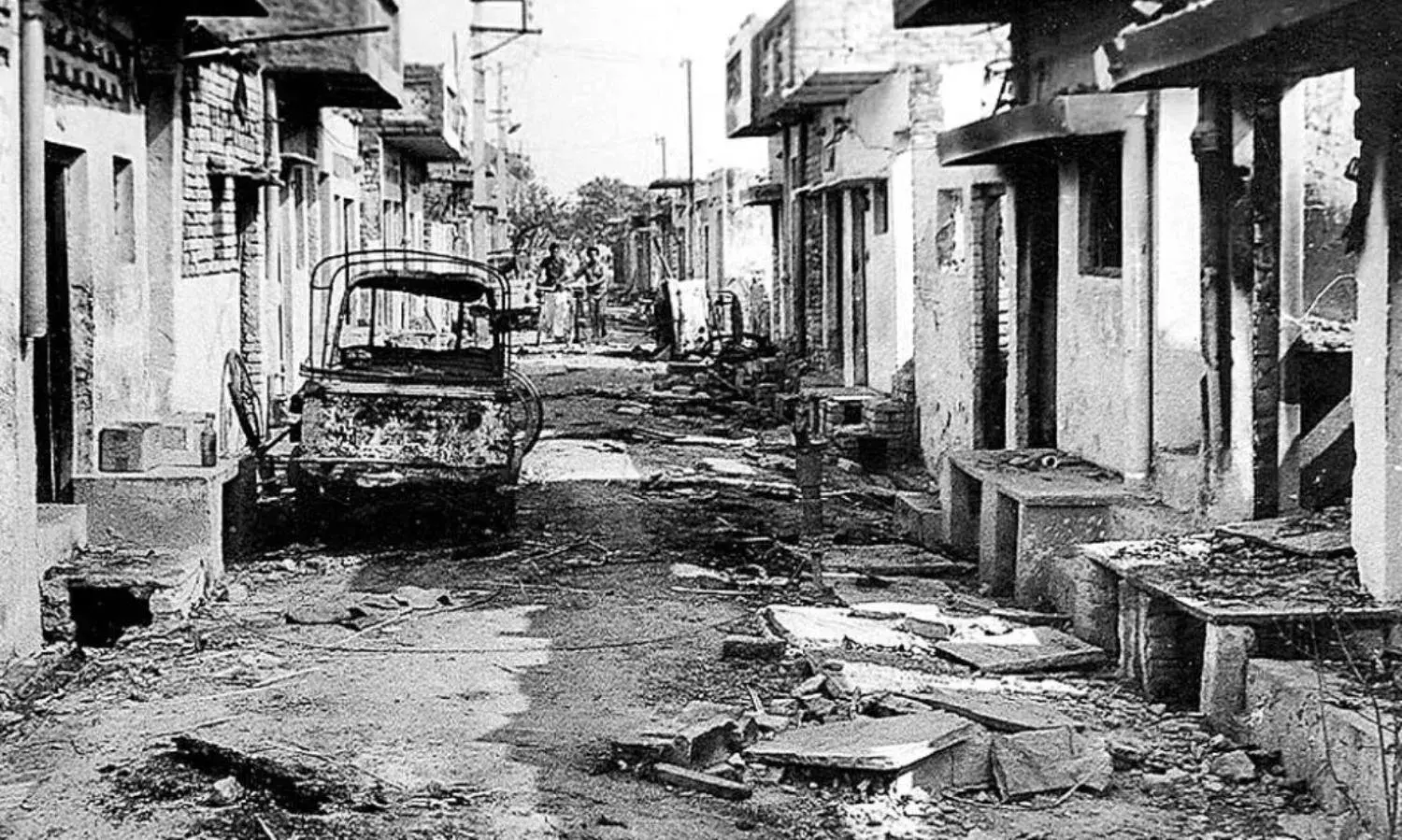

There were about 1,891 Sikh families in Bihar who suffered the brunt of the 1984 riots. Their homes, shops and vehicles were burnt. Some of these families had migrated to Bihar in 1947. Why? We all know the answer to this uneasy question.

The play is about a man who loses his entire family in the 1984 riots. He goes around searching for his family members, but in vain.

You know what happened to them? You know it happened to many Indians in the anti-Sikh riots, one of the most gory since the country was partitioned in 1947.

On November 4, 1984, early in the morning at 6 am, I went to the Patna airport to catch an Indian Airlines flight to New Delhi. To my utter surprise I found mostly Sikh families boarding the flight.

The plane made an unscheduled stopover in Kanpur. From the window I saw 20 or so more families walking to board the flight. All of them were Sikhs.

They were going to Punjab.

Back in my office located on Parliament Street in New Delhi, I was told that the three days from October 31 till November 2 were the days the vultures preyed.

On returning home, in Swasth Vihar on Vikas Marg, I found my rented home safe but the building to the right, which belonged to a very rich Sikh, had been burnt, cars in chars. The doors were broken and the house was empty.

It’s time I returned to my friend who was once a sardar! This is what he told me.

I had just reached the Kanpur railway station from Delhi when the riot broke out. I was in Kanpur to meet my sister who lived there with her family. From the platform one could see the vultures going at their prey. I knew not what to do?

“Don’t be mad to leave the station platform. You stay in the waiting room, it’s empty. I’ll try to bring some food for you. With your turban, you may not even be able to go for half a mile. They will kill you.”

That’s what a senior official at the Kanpur Railway Station told me. I spent the night at the railway station. By November 1, 1984 I was extremely anxious about my sister and her family members. They had no telephone connection at home.

I decided to risk my life. I knew that as a “sardar” I could not reach Kanpur’s Civil Lines where my sister lived. Anxiety was killing me and I finally decided to crop my hair and shake off my “sardar” look. I requested that railway employee to call for a barber. He sent for one. You know what happened next.

Next the railway employee hired a tanga (horse-cart) and I came to my sister’s home, only to hear that her father-in-law had been killed. Her husband, my brother-in-law, was lying half-dead in hospital. Their garment shop had been set ablaze.

The mob beat that old man of 71 to death and left my brother-in-law for dead in the street. But the local shopkeepers took him to a hospital. He survived.

“What are you doing now? Where are you, in Delhi?”

My friend told me his entire family had migrated to Canada after the riot. His brother-in-law had sold all his property in Kanpur and moved to Toronto.

He was in New Delhi to sell his ancestral house in the Green Park locality. He was going to sever all relationships with the nation of his birth and life, thanks to the riot of 1984.