'Politics is the Art of the Possible': Akeel Bilgrami on Secularism in India

The Centre for Policy Analysis hosts a talk on Secularism in India

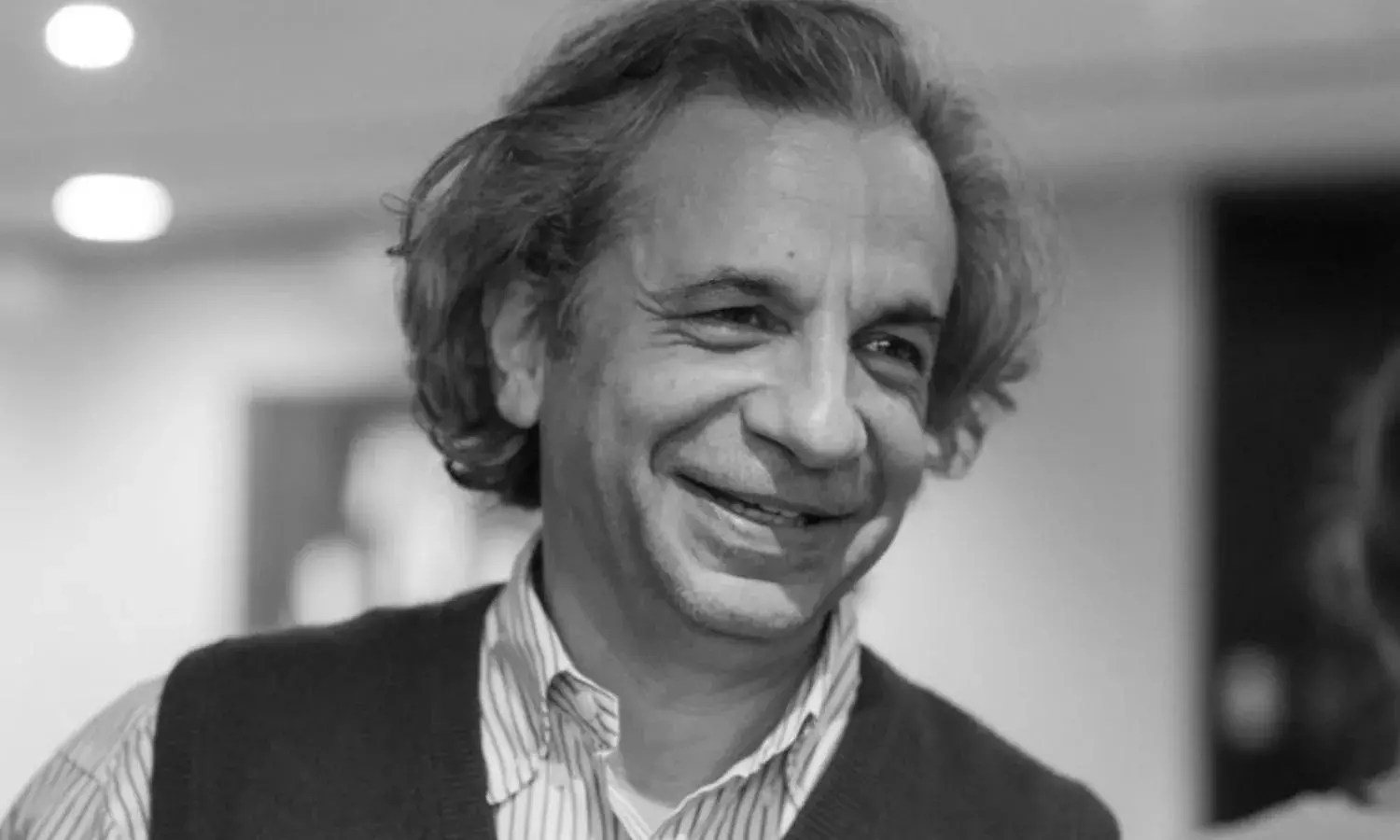

NEW DELHI: “You can never understand a concept or a notion in its entirety, until you understand that original situation from which it emerged. The same goes for secularism,” began Professor Akeel Bilgrami, in the annual lecture hosted by the Centre for Policy Analysis at the Constitution Club of India on January 14, speaking to a room teeming with senior bureaucrats, journalists, young activists and students.

Professor Bilgrami began with rooting secularism as an idea in the European context, saying the causes for its emergence in that continent in the 17th century were starkly different from its discourses in India.

“The concept of the nation-state was fused, generating feelings towards the nation to justify and legitimize the powers of the state. You identify an external enemy from within, unify the nation against it by subjugating and despising it.”

He defined secularism in its original definition as a concept that ushered out religious considerations from politics, to stave the backlash that sprang from minorities in Europe.

He drew comparisons to other oppressed groups throughout history, all subjugated on religious grounds, before moving on to Jawaharlal Nehru’s views on the subject by situating it in the Indian setting during the freedom movement.

“Nehru felt that secularism was never an exclusive concept to be discussed in India at all, because if secularism was a reparative notion towards a damage that had occurred in European society, he believed that damage to have never taken place in India in the first place.

“He instead referred to ‘un-self conscious pluralism’ of cultures, which had prevailed in India up until that time in the freedom movement,” continued Professor Bilgrami, “And that India’s unique nationalism was about replaying that pluralism to win the movement.”

He went on to draw a distinction between ‘antecedents’ and ‘roots’ in history, saying that he didn’t believe that the Khilafat movement was the root of secularism as a discursive topic in its present form in India, instead placing it in the 1980s, with the Mandal Commission Report.

“Hindutva emerged to unify the divided sections of Hindu society that had now been exposed. For the first time the European conditions were begin replicated in India. The right wing Hindu parties could assume the moral high ground by opposing the Emergency. The center-left didn’t show the courage to oppose it.”

Now he shifted track to focus the discussion on the emergence of multiculturalism, which was a “self conscious version of what Nehru said.”

“Secularism was too blunt an instrument to tackle the new issues that were emerging. If I were to make a broad simplification, what multiculturalism means is that every group is a minority. No group is a majority. So everybody’s interests are of equal importance. You couldn’t exclude religion from the discussion any longer like secularism aimed to do.”

He then turned his talk to the protests that have emerged across the country against the CAA-NRC, police brutality and infiltration of college campuses by right-wing groups, commenting on the political climate that has been brewing across the nation for the past one month.

“What the protestors are doing is extremely smart,” emphasized Professor Bilgrami, “Instead of defending a notion like secularism, they’re defending a concrete notion of the Constitution- that we have secularism enshrined in this document, let us now defend the document itself. Right now, national politics are not being fought at the parliamentary level, but at the street level.”

He went on to question what the corporates are doing at a time like this, saying that 80% of the corporates are dissatisfied with the current state of the “regime”.

“In my understanding, in any capitalist society, whatever the corporates want, happens. I fail to understand why so many of them are keeping quiet given everything that is happening and what everyone sees as the broad favoring of the ‘Gujarat Mafia’ by the present government.”

He concluded the talk by citing Antonio Gramsci’s theory of intellectualism, “The need for authoritarianism is removed, when you convince every class that its interests are everyone else’s interests. This what a hegemony does. Right now the movement is largely limited to the urban intelligentsia. When the Registry is implemented, the movement will likely spread. The population put up with something like demonetization- what is left to find out is if they will put up with something like this too."

The lecture was followed by a Q&A session, discussing “the fragility of the current stately resistance”, the vocabulary of scholars for the masses and Ambedkar’s thrust on legislation as opposed to Gandhi’s on movements.

“The state is just a bunch of tendencies. It is not a moral agent. It is like a gust of wind- only social and political, instead of natural,” concluded Professor Bilgrami before being facilitated with gifts marking the end of the event and the evening.

“Politics is the art of the possible. It’s like what Machiavelli said. Make the state fear you. And that is exactly what all the movements across India are starting to do now.”