A Commodity So Lucrative It Will Encourage Data Breaches: More on the Data 'Protection' Bill

Government can exempt itself anticipating a threat to public order

On December 11 the government tabled the Personal Data Protection Bill 2019 in the Lok Sabha. The first of its kind in kind in India where there are no laws yet to govern the flow and protection of data, the bill has earned its share of criticism for the sweeping powers it gives the political executive.

The stated purpose of the bill, according to Ruchira Sen, a political economist at the OP Jindal Global University, is to “safeguard certain rights of the individual citizen, such as the right to find out whether one’s personal data is being processed for targeted advertising, political advertising or other purposes, the right to correct irrelevant, inaccurate, or outdated data, and the right to withdraw consent from disclosure of data, i.e. the right to be forgotten.”

But the Data Protection Bill is not designed to do so, say privacy rights activists and internet companies. “It is inadequate and does not go to the extent required by a data protection law in order to safeguard a person’s fundamental right to privacy as was articulated in the Puttaswamy case [in 2017]” says Apar Gupta, a lawyer and executive director of the Internet Freedom Foundation, an NGO for digital rights and liberties.

According to Gupta, the bill does not propose any surveillance reform. Stressing on the need for a legal framework that must be followed in case of surveillance he said, “None of the reforms which exist in surveillance regimes across the world is under legislative contemplation right now under the existing data protection frame.”

Concerns over surveillance arose due to provisions in the bill exempting the central government from its purview. In Chapter VIII titled ‘Exemptions’ the bill assures the central government that “it may direct that all or any of the provisions of this act shall not apply to any agency of the government”.

This means that the central government can bypass all the safeguards and provisions of the bill which are there to protect individuals’ personal data from unauthorised access and use.

The central government can grant itself such exemptions “in the interest of sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, public order” and also to prevent offences being committed under these heads.

Initially drafted in 2018 by an expert committee headed by retired Supreme Court judge BN Srikrishna, the bill later underwent significant changes, including these exemptions the government has gifted itself.

The internet company Mozilla Corp expressed concerns on their blog about these exemptions saying, “This leaves the current legal vacuum around India’s surveillance and intelligence services intact, which is fundamentally incompatible with effective privacy protection”.

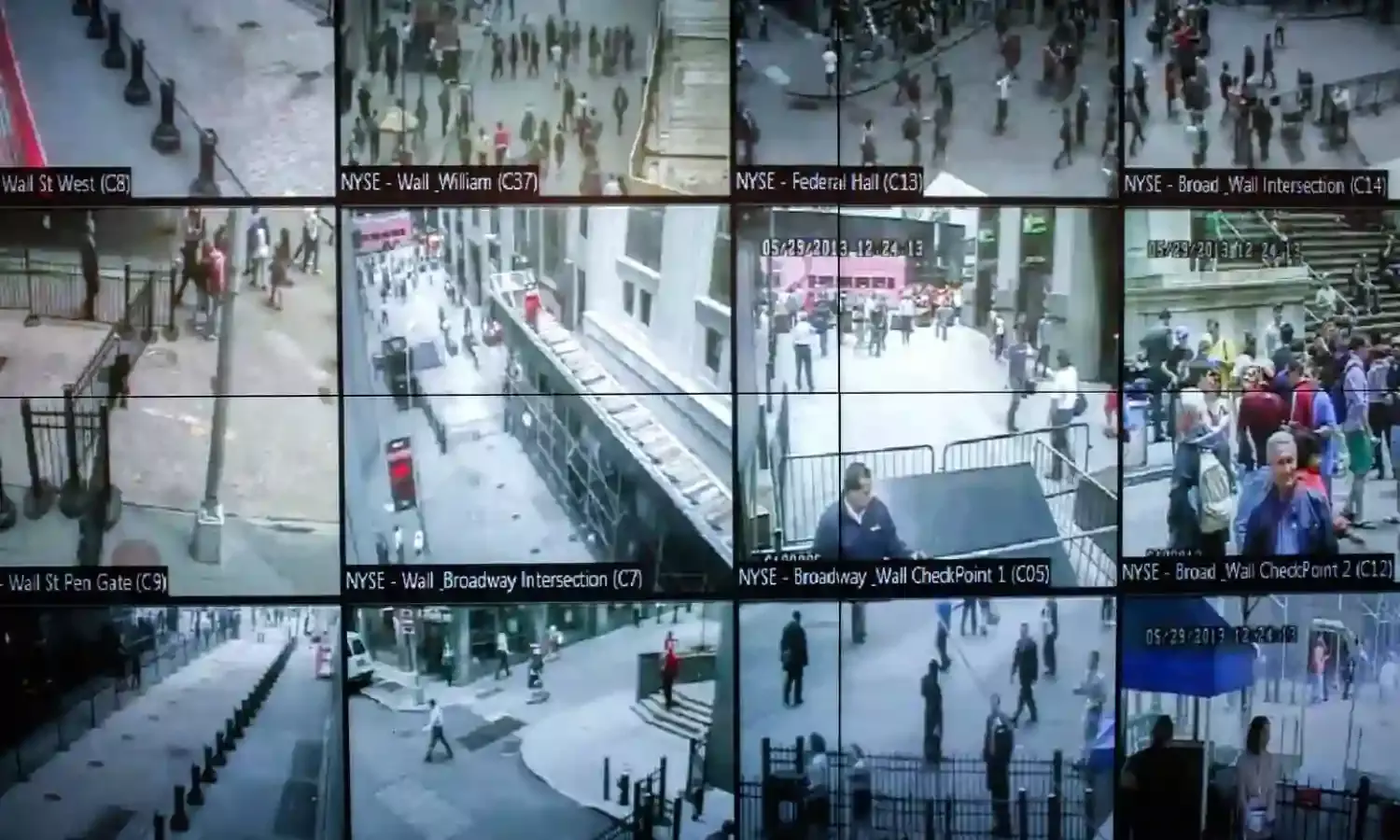

Ruchira Sen observes that “This comes at a time when the State has drones flying over protests and is using facial recognition software to make a database on protestors. In a political atmosphere where any dissent against the State is declared ‘antinational’ and dissenters are otherised, and thereby stripped of their rights as citizens, the exemptions granted to the State to access the personal data of citizens without their consent are indeed concerning”.

Clause 28 of the bill requires specific social media companies to provide a platform for their users to voluntarily verify their accounts “in such manner as may be prescribed” - this may include uploading government-issued IDs for identity verification.

Sen described how linking personal user information to state-issued IDs can create a huge database of citizens’ profiles.

“If it involves linking personal user information such as ‘likes’ on Facebook or Twitter with government IDs, it will become theoretically possible to build detailed databases linking people’s voter IDs, PAN cards, bank account details, Provident Fund accounts, car registration numbers and what not - a commodity so lucrative that it will incentivise data breaches.

“Just imagine how powerful one can be if one knows almost every detail of a population’s life,” Sen told The Citizen.

The bill also seeks to regulate the storage and processing of Indians’ data in foreign nations. However, according to Sen the bill is unclear about restrictions on transferring Indians’ data abroad.

“Most of the world’s communications pass through the USA as it is the most centrally connected via internet bandwidth. It’s cheaper to communicate through the USA even if it means that any particular communication must pass a longer distance, as revealed by the [National Security Agency’s] PRISM slides leaked by Edward Snowden,” she said.

Regarding the protection of Indian citizens’ data from US government agencies, Sen said “The FBI has been known to collect data from data fiduciaries such as Google and Facebook. How can the PDP bill protect Indian citizens from having their data transferred to US government agencies?”

There is also the burden of data entry and data processing, and its effect on health data systems in India, as Sen pointed out. “Health data systems in India can involve the inputting of data by time-scarce care providers on multiple systems, which impacts the time they can spend on care. There is no discussion on streamlining data systems such that no data is collected more than once, and duplication of efforts and redundancy is avoided”.

The bill proposes to establish a Data Protection Authority whose members will be chosen from those recommended by a selection committee. In the 2018 draft bill the selection committee was to comprise the Chief Justice of India or a Supreme Court judge nominated by them, the Cabinet Secretary, and an expert individual nominated by the CJI in consultation with the Cabinet Secretary.

However, the government modified the bill last year to propose a selection committee drawn entirely from the executive. It omits the CJI or any expert individual, and will consist only of the Cabinet Secretary and two Secretaries: in the ministry or department dealing with legal affairs, and with electronics and information technology.

Last session the union minister for electronics and IT Ravi Shankar Prasad sent the bill to a Joint Parliamentary Committee for scrutiny. The 30-member committee is headed by BJP MP Meenakshi Lekhi and agreed on January 16 to invite suggestions from the public about the bill.