Amphan: Kolkata Gathers its Fragments Together, Led by the Young

'We were all suffering from tremendous survivor's guilt.'

KOLKATA: “We saw the pictures initially; we could not imagine ourselves in their situation. The pictures were horrifying,” said a resident of Kolkata.

On May 20 the super cyclone Amphan slowly began to unfurl before the city’s eyes. In a matter of hours, lanes that had reeked of the silence and emptiness of lockdown were experiencing a deluge of water and destruction, as trees draped round with cable wires began falling to the ground.

Always the city of solace, brimming with hope and the rattling of trams and the lingering aroma of fish, the spirit of Kolkata had already been dampened by the lockdown. The cyclone was undoubtedly alarming, but more upsetting were the stories that surfaced after the calamity.

“Sab tut gaya baji. Ham log soya nai” (Everything broke apart, sister. We could not sleep), said Rabia Begum, 40, a domestic helper who lives in East Kolkata.

“A few family members came and took us away, the roof was falling. It was not safe” said another resident, who watched the cyclone slowly devastate the clay-tiled roof of her house.

While the city struggled for days without electricity or communications, it was evident that the poor who were bearing the brunt of the lockdown in the form of dispossession and hunger, now found themselves in the eye of the storm. As the worst affected began to look for help and support, it was clear that help might take days to come.

Although nothing can match state efforts to rescue and rehabilitate those affected by the cyclone, the initiative and support rendered by young Kolkatans has indeed been phenomenal.

A group of 8 students teamed up to rebuild, support and comfort the booksellers in Kolkata’s well known College Street, Asia’s largest book market.

A 900 metre stretch comprising booksellers big and small with their books spilling over on to the pavement and readers bargaining aggressively, ‘Boi Para’ (College Street) has long celebrated the art of reading. But as nature would have it, Boi Para was devastated mere hours after the cyclone hit.

The team of undergraduate and postgraduate students are leading a non-government, nonprofit initiative called the College Street Relief Drive to support the booksellers.

“We were all suffering from tremendous survivor’s guilt. We saw what was going on around us and to say our hearts were broken would be an understatement. This was the bare minimum we knew we had to do,” said one of the volunteers.

Over several days the initiative was able to raise over Rs.2 lakh for at least 56 beneficiaries.

To decide who among so many booksellers most needed their support, a team member said they “checked their official documents, enquired about their income before the lockdown and the cyclone, and then queried and approximated their capital losses. We talked to the employees of the bookshops, and only when we sensed their monetary requisite was spot-on, we would pass on the amounts in their bank accounts.”

Recalling the horrors of Amphan, Suchintan (21) one of the members of the initiative told the story of Shubramoy Puddor. A bookseller on College Street, with a wife and two children, Puddor found their survival threatened after the cyclone: “He did not even have money to buy ration. There were absolutely no sales during the lockdown, and now that the books were ruined, he had no choice but to ask for help.”

Another team member, Medha Ghosh (21) told us how she “personally called up this bookseller, and he started crying. He lost everything in the cyclone. He used to travel 10 to 15 kilometers to deliver books to people’s houses to make a living. After the lockdown and Amphan there was no income whatsoever.”

Although the booksellers were part of various guilds and local organisations that were expected to render some support, they knew this might just not happen. So they demonstrated an immense degree of solidarity.

The CSRD team shared instances where booksellers would ask for help collectively, rather than giving them individual approximations of their losses. “Don’t just help me, help my brothers too,” they were told.

The solidarity that came about through sitting together, eating together, drinking tea together and surviving the cyclone together remained after the tragedy. When the team approached one renowned bookshop, the owner refused to take any amount from them, saying “We do not need help. Please help the small book sellers.”

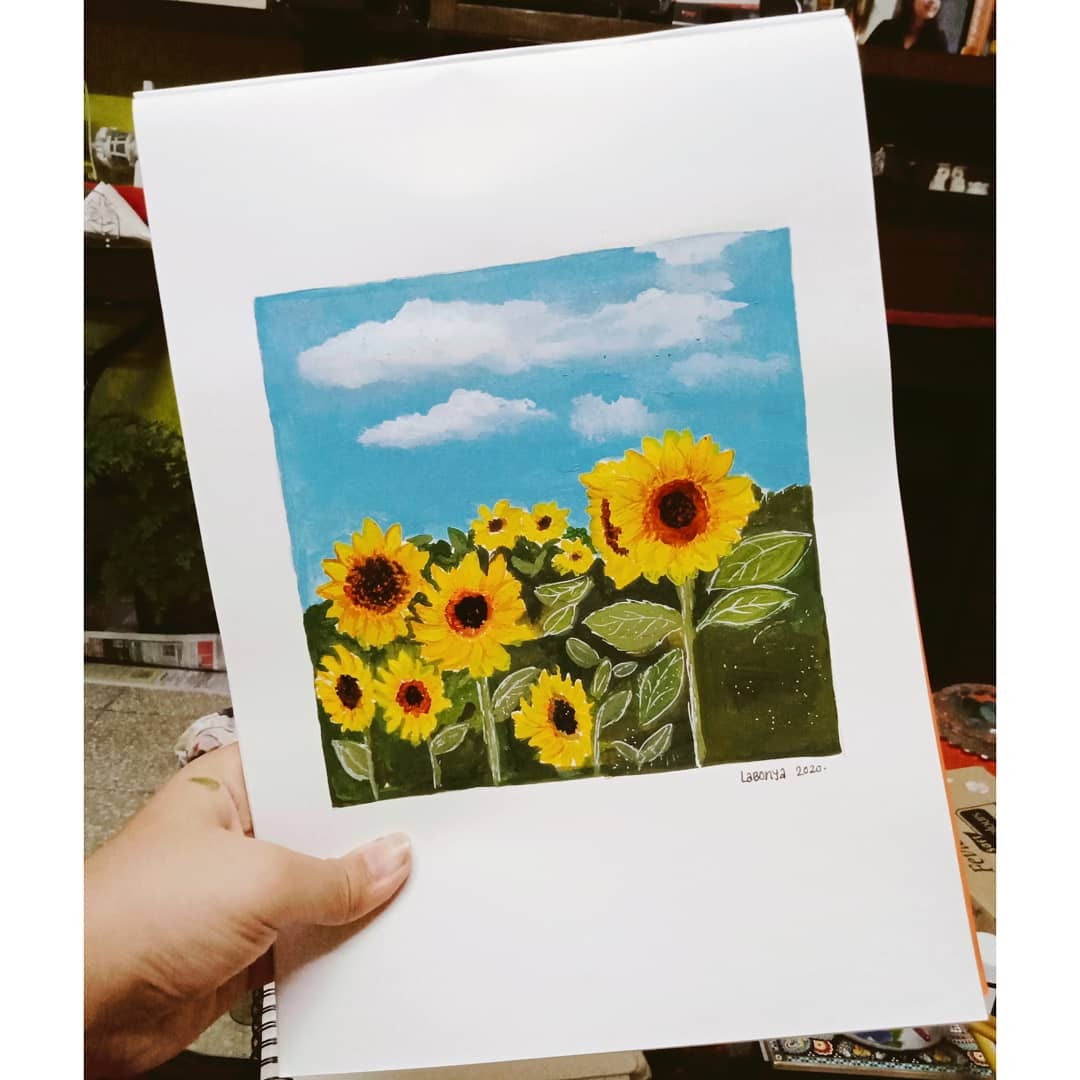

Another such relief effort is underway through another non-government non-profit body called the Curry Project based in Kolkata. Labonya Chaudhuri, 20, one of the several artists working with the group, said they have been raising funds by using their skills in art.

“We stated our lowest prices for our artwork. Since we specialise in different forms of art, the idea was that people would place an order for their desired sketch, and in return for the artwork of their choice, the amount they paid would be donated entirely for the cause of the affected.”

Chaudhuri shared that even though these young artists are taking no money for their work, “I get a platform for my artwork, and I feel a sense of satisfaction since my efforts and skills are being utilised for a good cause.”

Project leader Ritwika Paul said they came up with the idea to “give individuals an incentive to donate”. They realised that support could be redirected to the affected through different media: the Curry Project also plans to hold acting workshops online, conducted by well known actors, and will donate the entire registration fee towards government and civil society relief efforts.

It has been said that each tragedy gives us an opportunity to rebuild. Kolkata seems to be gathering its shattered fragments together after Amphan, piece by piece and brick by brick, to keep life moving forward— and this time the young might be leading the venture.

Aniba Junaid is currently an undergraduate student at the Loreto College, Kolkata