Season of Youthful Protests Inspires Urdu in India

Protest poems and songs have revived Urdu among India’s youth

In 1985 Iqbal Bano stood in front of a 50,000 strong crowd, clad in a beautiful black saree, and sung Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s Hum Dekhenge, bringing about a spirit of revolution to one and all. In 2019, Jawaharlal Nehru University’s Shashi Bhushan ‘Samad’, a visually impaired young scholar, sang along to Habib Jalib’s Dastoor at a protest site, another ode to dissent and revolution.

Their attire and age wasn’t the only thing different. Bano used poetry in Urdu in a country that had accepted Urdu with open arms, a bit too tightly perhaps. But Samad echoed verses from a language that had been systemically and subconsciously pushed to the backseat.

Until, of course, the season of youthful protests brought back the fragrance of Urdu to the mainstream.

It is not a new claim that Urdu is losing ground in India. From being the tongue of the Lucknowi speakers and Delhi traders to the signboards of Uttarakhand and Bihar, and legislations of Jammu and Kashmir, Urdu has been dying a very audible death.

Was it because of the Imperial hangover of English education or the communalised Hindi–Urdu divide? The fact remained that Urdu had been left outside the scheme of things. But late 2019 into early 2020 brought with them a wave of young exuberance in the form of protests for reduced fees for higher education, freed expression, safety from assaults against varsities, and dissent against the Citizenship Amendment Act and National Register of Citizens.

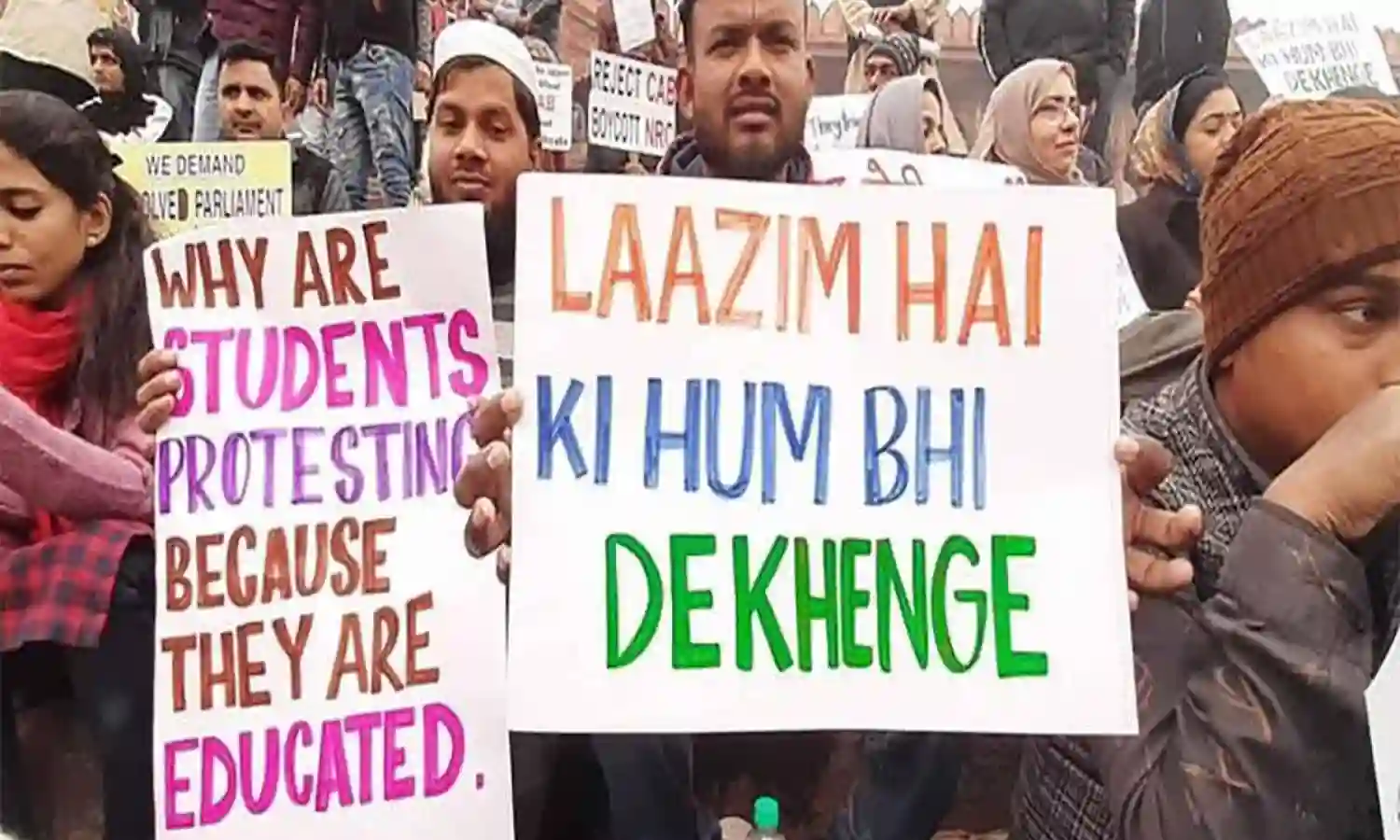

These protests, led by young, brave and spirited people from all communities and cultures, soon took towards revolutionary rhymes in Urdu: inquilaabi shayari, nazms and ghazals were soon flooding the nation’s cultural landscape and have brought back the Urdu language into the headlines, and the tongues of people.

Ever since November 2019, students across the nation protesting as one pluralistic bloc have quite naturally used Urdu poetry on banners and posters, as slogans and battle-cries, to convey their anger, resentment, hope and spirit against an establishment that wants to erode the very bond they cherish.

The poetry of a student of Jamia Millia Islamia, Aamir Aziz, gripped the entire nation in awe as it felt its pain through Sab Yaad Rakha Jayega.

Not just original work, but classics like those of Habib Jalib, Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Allama Iqbal and Ahmad Faraz were reverberating through the country’s mainstream media. Searches for famous revolutionary poets increased tremendously during the period of protests and resistance:

Internet trends show huge spikes for searches about Urdu poets

Those few months also led to increased interest among Indians in the shared heritage of Urdu and Hindustani with Hindi, Khari Boli, Dakhni, Dehlavi, Awadhi, Brajbhasha…

Sirajuddin Ajmali, former chairman of the Department of Urdu, Aligarh Muslim University explains:

“The beauty of the Urdu language is in its sweetness of rhythm, its politeness. As more people hear it for themselves via the television broadcast and viral videos of the protests, of the people reciting poetry in resistance, it enchants whoever listens. Urdu is a passionate language and no wonder that it finds itself in the place among youth and resistance. Maulana Hasrat Mohani gave us the slogan Inquilaab Zindabaad, after all.”

Another reason why the language is finding supporters among the young is that through Urdu they are able to transcend the divides of communities and nationalities.

Ajmali believes the current generation, especially university students, can see through the politicisation and communalisation of language, and is choosing to overcome that barrier.

Amrit Mahapatra, a sociology student at the Buxi Jagabandhu Bidyadhar Autonomous College, says he has been interested in Urdu for about a year, but his attraction peaked during the anti-CAA-NRC-NPR protests:

“Songs like Hum Dekhenge or the like captured the attention of the masses. For me it was simple: it was brilliant literature and it encapsulated whatever I felt about it. Made me feel fearless. I’ve been visiting Coke Studio Pakistan so many times since then. Language truly knows no boundary or hatred,” says Mahapatra.

A key reason the current generation can rediscover Urdu is the availability of its literature in scripts other than the traditional Perso-Arabic. Websites such as Rekhta, Ishq Urdu and A Desertful of Roses have created a culture of sharing Urdu poetry in the Roman and Devanagri scripts as well.

“Even though I don’t think the popularity of Urdu poetry in other scripts helps to spread the actual language, the grammar and script of the Urdu language, it certainly helps acquaint people to the idea that Urdu and Hindi are not so different, in fact, they are sisters in the language family tree. But for Urdu to truly flourish, governments need to work sincerely and solidly,” says Salim Saleem, a member of the Editorial Board of Rekhta, an organisation working for the preservation and progress of Urdu.

These last few months have given Urdu in India a new lease of life. Whether it will flourish or sink back… Hum Dekhenge.

Ansab Amir Khan is a student of Aligarh Muslim University and an aspiring journalist