Muziris, Ancient Gateway on the Kerala Coast, Brought to Life

What makes Kodungallur truly Indian is its composite culture

When incessant rains gripped the whole of Kerala for three successive days in August 2018, locals with a penchant for history felt it almost as a replay of the catastrophe that washed away the ancient sea port of Muziris in 1341.

Periyar, the state’s second largest river which divides Kerala into north and south, was in spate ever since the morning of August 14, inundating most parts of Idukki, Ernakulam and Thrissur. People’s lives, homes, valuables and precious places faced a surging threat from the waters, and so did the treasured historical legacy of this ancient port town.

A number of prized archaeological remains of the legendary port town were lost to the flood.

According to Kerala historians, Muziris was situated at the exact point where the river empties into the Arabian Sea. Forming the Kodungallur– Paravur belt, the shores of the river hold strong archaeological evidence of centuries-old Kerala as a cultural and commercial hub, networked with ancient cities like Rome.

The Flood of 1341

“The apocalyptic swells of Periyar in 1341 erased this urban centre totally,” says S.Hemachandran, former director of the state government’s archaeology department, who has conducted in-depth studies of the region and its history.

Those massive floods destroyed not just the transcontinental trade ties but also various remnants of the ancient port town, which had brought the Malabar Coast and its spices onto the world map.

Fortunately this time the waters receded by August 16 in the evening without the level of destruction that occurred in 1341.

According to Rubin D’Cruz, a scholar who works with a Kerala government initiative to preserve the historical importance of the lost port town, the legacy of Muziris starts from around 3000 BC, when Babylonians, Assyrians and Egyptians came to the Malabar Coast in search of spices.

Later they were joined by Arabs and Phoenicians, and the port town gradually entered into the cartography of Old World trade. An integral part of those ancient trade routes, Muziris now holds the key to a rich seam of Kerala’s ancient history.

In stories of Rama’s adventures Muziris was Muchiripattanam, the forest whence the forces of the monkey king Sugriva start their search for the abducted Sita. Tamil Sangam poems from the early centuries CE desribe the numeral Roman ships landing at Muziris laden with gold to exchange for pepper.

According to the first century accounts of Pliny the Elder, and the contemporary periplus of the Erythrean Sea, Muziris could be reached in a fortnight from the Red Sea ports on the Egyptian coast if you were purely sailing on the monsoon winds.

Gateway of Semitic Religions

“Going by the excavations in present Kodungallur and surroundings, Muziris was a major Buddhist centre in the South. The ancient Kurumba Bhagavathy Temple located at the heart of Kodungallur was once a Buddhist centre of worship and it became a Hindu shrine when the locals abandoned Buddhism. The region had a strong Jain presence as well,” says T.M. Thomas Issac, a native of the region and finance minister in the Kerala government.

“Despite being a major Hindu pilgrimage centre, the region holds the unique distinction as India’s gateway of all the Semitic religions: Islam, Christianity and Judaism. No other settlement in India can claim such a history, and the region has a long history spanning over 2,000 years of communal harmony and social solidarity.”

Muchiri Pattanam evolved into Muziris and Kodungallur over the years. Muchiri in Malayalam means cleft lip and it is said to denote the three branches of the Periyar which empties into the Arabian Sea close to town.

Legends say that Christ’s apostle St Thomas landed in Kodungallur in 52 CE. A church commemorating the event stands at Azhikode, where Periyar merges with the sea. The town also had a flourishing Jewish settlement till recent years when most of the residents moved to Israel.

A burning time-honoured lamp welcomes you to Kondungallur’s Cheraman Masjid, reputedly the world’s second and subcontinent’s first centre of Islamic worship.

“The lamp has been burning here at least for the last thousand years and people of different faiths are still bringing oil for it as offering,’’ relates Mohammed Sayeed, president of the managing committee of the historic mosque.

He shows how the inner portions of the structure were built centuries ago in a seemingly Hindu architectural idiom. The old rosewood pulpit from where the imam recites the Friday sermon is covered with exquisite carvings imbibing the style that prevailed in the region at the time.

Believed to have been established in 629 CE, the mosque now stands as a powerful symbol of social solidarity and communal amity, a counter to communal polarisation.

The state government has allocated Rs 1.13 crore of public money to renovate the Cheraman Mosque, which involves removing structures of recent origin that are mismatched with the original mosque, in an effort to recreate what existed in the beginning.

“Kodungalloor is rich in monuments of Kerala’s history: churches, temples, synagogues and historical places. The restoration will be undertaken in tune with the original character and aesthetics of the mosque, as part of the Muziris Heritage Conservation Project, which aims to revive and restore these structures to espouse the cause of unity and amity,’’ says Issac.

According to Benny Kuriakose, an architect and the brain behind the Muziris Project, “Legend has it that the mosque was originally a Buddhist place of worship with a huge rectangular pond on one side, and it was maintained by the Cheraman Perumal dynasty of nearby Mahodayapuram.

“But the last among the Cheraman Perumal kings probably found an ideological vacuum when Buddhism declined and he soon embraced Islam. He had travelled to [the Arabian peninsula] and met descendants of the Prophet. But he died on his return in present-day Yemen. The mosque was constructed at his instruction.”

Just before his death, Cheraman Perumal is believed to have instructed his travel companion the Persian scholar Malik bin Dinar to construct the mosque, and to spread the message of Islam in his homeland. The place of the mosque is called Cheraman Malik Nagar in their honour.

Festival of colours at the Kurumba Bhagavathy Temple

A little away from the mosque stands the famous Kurumba Bhagavathy Kavu or Kodungallur temple where the Meena Bharani festival invites national attention through its uniqueness and vibrancy.

Normally happening in April, the festival turns a riot of colours with thousands of red-clad oracles marching, their foreheads smeared with turmeric, clanging their anklets, belts and ritual swords.

They will sing to bamboo rhythms. The atmosphere will be charged with the intense expressions and frenzied dance of the oracles.

Devotees say they allow the presiding deity to pass her energy through them by being oracles. In the festival’s peak days, male oracles clad in saris and adorned with ornaments in the image of the goddess outnumber the women.

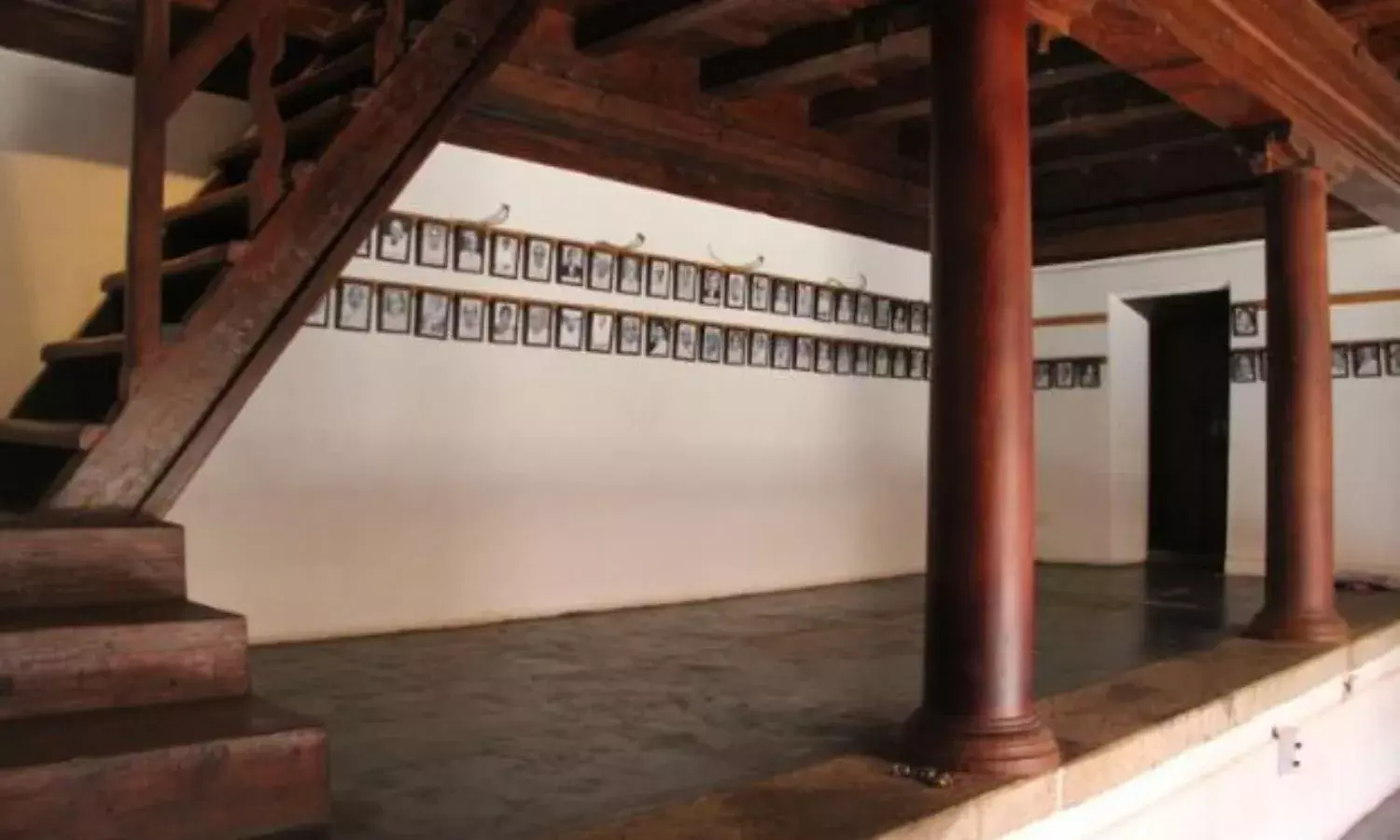

The Muziris Heritage Project, which stretches across seven panchayats in Kodungallur and adjacent Paravur, will have 27 museums and more than 50 sites of interest ranging from a spice museum to an excavation site where shards of Roman amphorae and Italian ceramic ware have been found.

In the initial phase, two synagogues abandoned by Kerala Jews who left for Israel in 1948 have been restored and opened to the public.

Back in 2000 some local residents found colourful ancient beads in the mud following rains, heralding a new chapter in Kerala archaeology. Excavations were begun in 2007.

“In the last 12 years, we have recovered more than 95,000 objects, ranging from glass beads to fragments of pottery pieces from Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq,’’ says Rubin D’Cruz.

There is also Chendamangalam, a weavers’ village, which lies between Kodungallur and Paravaoor. Earlier it was the seat of the Paliath Achans, prime ministers of the erstwhile princely state of Kochi.

Besides the weavers and their work, which makes the finest handloom textiles and wear, the major attraction here is the Paliyam Palace, built in the Dutch architectural style by the Paliath Achans. A nalukettu or four-winged house used by women and children of the Paliath family in the past is another attraction in the village.

The Muziris heritage boat ride facility which recently started operations helps travellers explore the whole region. The boats connect historical sites in the coastal villages Paravur, Pallippuram, Kottappuram and Gothuruth, encircled by the backwaters, and Kodungallur.

Above everything else, what makes Kodungallur truly Indian is its composite culture. There are Muslim households with Hindu-seeming names and Hindu festivals with non-Hindu influences. A number of Christian families follow shared traditions with Hindus.

The Muziris Project will bring to life a rich tradition of coexistence to the world outside, where we busily create divisions.