Support Pours in for Agitating Farmers, Top Economists Write to Tomar

Maharashtra farmers set out for Delhi

Despite the best efforts of the ruling dispensation and the pliant media to discredit the farmers’ protest at the borders of Delhi, the movement has started getting support from other states as well busting the attempts to present the farmers movement as Punjab centric with a Haryana spill over at best.

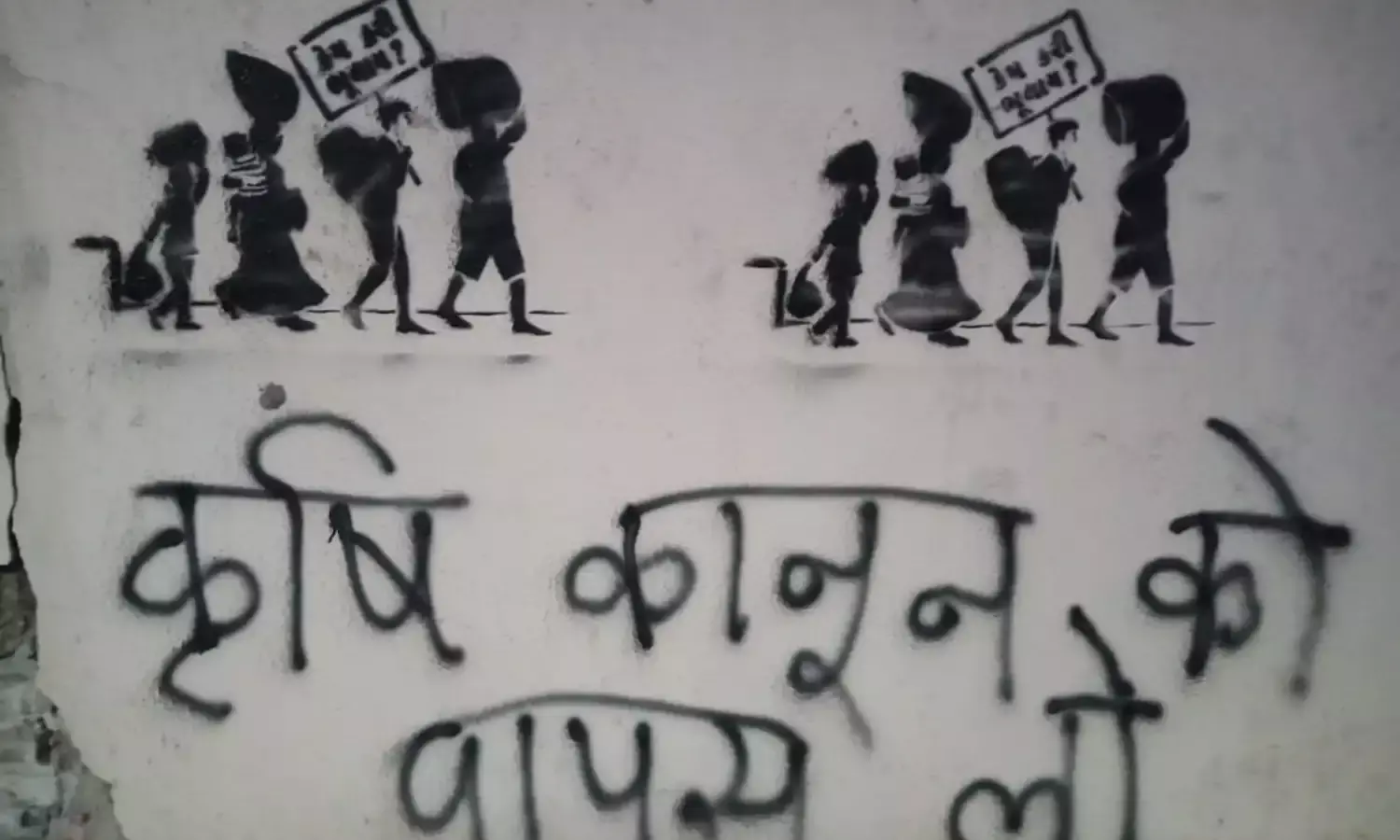

Ahmedabad woke up to graffiti in support of the farmers’ movement. There were wall paintings and slogans visible at no less than half a dozen prominent spots like near Gujarat College, Lal Darwaza and District Panchayat Office. Anonymous graffiti artists had linked the plight of the migrants to the ongoing farmers movement. More so, as under the pretext of the pandemic the authorities in Gujarat have not been allowing people to gather for protests.

“But wall writing and graffiti is also a means to express your dissent and support for those fighting for a larger cause,” social activist Hozefa Ujjaini told The Citizen.

Meanwhile, thousands of farmers in Maharashtra are expected to gather at Nasik on Monday and begin a march on vehicles towards Delhi. All India Kisan Sabha president Ashok Dhawale said, “Initially, only 2000 farmers will go to Delhi while the remaining will accompany them to the Maharashtra border. Farmers from Madhya Pradesh are already camping at Palwal border. The agitation against the anti farmer laws will be intensified in the days to come.” A large number of farmers from Rajasthan already camping at the Delhi border, ad succeeded in blocking the highway to Delhi for a few hours on the day of the bandh.

Meanwhile, a group of senior economists have written a strong letter to Union Agriculture minister Narendra Singh Tomar expressing serious concerns about the three farm laws, and calling for their repeal.

The letter has been signed by Professors D.Narasimha Reddy of National Institute of Rural Development, Kamal Nayan Kabra of Indian Institute of Public Administration, K.N. Harilal of Centre for Development Studies, Trivandrum, Rajinder Chaudhary of M.D.University, Rohtak, Surinder Kumar of Centre for Research in Rural and Industrial Development, Chandigarh, Arun Kumar and Malcolm S. Adiseshiah of Institute of Social Sciences, New Delhi, Ranjit Singh Ghuman of CRRID, Chandigarh, R.Ramakumar of Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, Vikas Rawal and Himanshu of Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

They have clearly stated, “We do believe that improvements and changes are required in the agricultural marketing system for the benefit of millions of small farmers, but the reforms brought by these Acts do not serve that purpose. They are based on wrong assumptions and claims about why farmers are unable to get remunerative prices, about farmers not having freedom to sell wherever they like under the previously existing laws, and about regulated markets not being in the farmers’ interests.”

The economists have substantiated their viewpoint saying, “Making a Central Act which overrides and undermines the role of state government in regulating agricultural markets is a flawed approach, both from the point of view of Centre-State power balance and also from that of the farmers’ interests. State government machinery is much more accessible and accountable to farmers, right down to the village level, and hence state regulation of markets is more appropriate than bringing a large part of commodity sales and trade under the ambit of the central Act, by establishing ‘trade areas’.”

Ministry of Agriculture figures say that in July 2019, more than 20 states had already amended their Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC) Acts to allow for private mandis, e-trading, electronic payments, e-NAM, etc, with all of them functioning under the regulation of the state government.

“For any such reforms or new mechanisms to succeed, there has to be a buy-in from all the stakeholders in the market including farmers, traders, commission agents, etc, and this process can be handled with more sensitivity and responsiveness to local realities by the state government, rather than through a drastic and blanket legislative change at the central level,” the letter contends.

They have underlined that a key problem with the Acts is the creation of a practically unregulated market in the ‘trade area’ side by side with a regulated market in APMC market yards, subject to two different Acts, different regimes of market fees, and different sets of rules.

This is already causing the traders to move out of regulated markets into unregulated space. If collusion and market manipulation are concerns inside the APMC markets, the same collusion and market manipulation are likely to continue in the unregulated market space. Within the regulated APMC markets, there exist mechanisms to address and prevent such market manipulation, whereas in the unregulated ‘trade areas’, the central Act contemplates no such mechanisms.

Means of exploitation of farmers include price and non-price issues such as weighing, grading, moisture measurement, etc. In a dispersed situation, farmers are rightly afraid that fairness cannot be ensured on price and non-price factors. Their experience shows that such exploitation is faced at a much higher level by farmers in remote areas which do not have access to structured markets, including tribal areas.

“Even before these Acts came, a large percentage of the sale of agricultural commodities happened outside the APMC regulated market yards. However, the APMC market yards still set the benchmark prices through the daily auctions and offered some reliable price signals to the farmers. Without these price signals, the fragmented markets could pave the way for local monopsonies. The experience in Bihar since the removal of its APMC Act in 2006 shows that farmers have less choice of buyers and less bargaining power, resulting in significantly lower prices compared to other states,” the letter underlines.

Referring to contract farming, the economists have pointed the issue of the huge asymmetry between the two parties, small farmers and companies, is not addressed to provide adequate protection to the interests of the farmers. The current scenario is likely to continue, where most of the contract farming happens through unwritten arrangements with no recourse for the farmers, and most arrangements are made through aggregators or organizers to protect companies from any liability.

The Act doesn't have any provision to address this. Further, the farmers are concerned that the provisions for farm services agreements together with the government's moves towards a liberalized land lease regime would pave the way for larger scale corporate farming.

“It should be noted that while contract farming arrangements are voluntary in principle, the acute crisis in agriculture with no price assurances, may push farmers towards this paradigm in the hope of saving themselves from the crisis. However, the reality of contract farming experience doesn’t bear that out in the absence of mechanisms to protect their interests,” the letter says.

The economists have stated, “ It is legitimate to understand that the three Acts together represent unshackling of agri-business companies from state level regulation and licensing, constraints such as existing relationships between farmers, traders and market agents, and from limits on stocking, processing and marketing.

This rightly raises concerns about consolidation of the market and the value chains in agricultural commodities in the hands of a few big players, as has happened in other countries such as the USA and Europe.

It inevitably led to the ‘Get-Big-or-Get-Out’ dynamic in those countries, pushing out the small farmers, small traders and local agri-businesses. Instead, what Indian farmers require is a system that enables better bargaining power and their expanded involvement in the value chain through storage, processing and marketing infrastructure in the hands of farmers and farmer producer organizations.

That would be a path for enhancing farmer incomes, and some of the earlier policy initiatives of the government were expected to help in that direction. However, the present Acts set a different direction where it is up to agribusiness companies, freed from regulation and constraints, to invest and set up processing, storage and marketing infrastructure – consolidating their hold on the value chain – while the government steps back from its commitment to help farmers build infrastructure and consolidate their bargaining position in the market.”

The economists have clarified that amending a few clauses will not be sufficient to address the concerns rightly raised by the farmers. “We strongly believe that it is not desirable to perpetuate the impression that farmers are misled by others, when they are raising valid and genuine concerns. The current impasse is not in anyone’s interests and it is the responsibility of the government to proactively resolve it by addressing the farmers’ concerns,” the letter says.