Urdu, and Hindi

'Ask me something in Hindawi that I may speak sweetly'

In our part of the world, when we talk about polar opposites certain names spontaneously come to mind, like Kashmir and Kanyakumari, or India and Pakistan. The irony is that India and Pakistan (and Bangladesh) are much closer to each other, geographically and culturally, than we make them out to be.

And unsurprisingly the primary official languages both these states have adopted (Hindi, and Urdu) are also much closer than they are made out to be.

Great ambiguity persists on the origins of the language now known as Urdu. We don’t have a definite answer to when the language “began” or what exactly was “early Urdu”.

An internet search for the first Urdu poet directs one to the 13th century poet Amir Khusrau, who indeed wrote that he had composed some verses in what he called Hindawi, but was not including them in his collected works. None are known to have survived, though many such compositions sung today are attributed to Khusrau, who wrote in the preface to his third diwan:

“I have scattered among my friends a few chapters of Hindawi poetry also, but I would be content here with a mere mention of this fact… As I am a parrot of India ask me something in Hindawi that I may speak sweetly.”

The question arises, why would Khusrau’s Hindawi be recognised as Urdu and not as an archaic form of Hindi? When that same language is also recognised by names such as Dehlavi, Rekhta and so on.

There is no disputing the fact that the word “Urdu” is a Turkish word meaning army or camp, and lent itself to the English word horde. This has led to the most popular creation myth of the “origin” of Urdu – that it was an army language.

The myth was propagated primarily by Mir Amman, who worked as a translator at the Fort William College, Calcutta. In his book Bagh o Bahar he suggests that during the reign of Shah Jahan, the army consisted of people from many linguistic backgrounds making communication among them difficult. Therefore they merged the lexicons of their own languages to come up with one that would be comprehensible to all, and would help facilitate communication within the army.

The state of affairs is such that even some present-day teachers of Urdu believe this myth.

Noted Urdu scholar the late Shamsur Rehman Faruqi points out that Urdu was never the name of a language in the first place, but rather the name of a place. He cites the Delhi poet Arzu (1687–1756) who in his work Dad e Sukhan referred to Shahjahanabad (Old Delhi) as the Urdu of Hind or Camp of India.

Elsewhere Faruqi points to a couplet by Musahafi (1747–1824) which again refers to the city as Urdu rather than the language – which is called Rekhta:

Albatta Rekhta Mein Hai Musahafi Ko Daava

Yaani Ke Hai Zabaandaan Urdu Ki Wo Zabaan Ka

Musahafi has, most surely, claim of superiority in Rekhta

That is to say, he has expert knowledge of the language of the Urdu

Shahjahanabad was referred to as Urdu e Mu’alla, or the exalted camp, and the language spoken by its residents was known as Zabaan e Urdu e Mu’alla or the language of the exalted fort or camp.

This language did have popular names at the time: people most often referred to it as Hindi, Hindustani, and Rekhta. Whatever some extremist groups may assert today, going by the literature available it would be absolutely correct to say that Hindi was the language of the Urdu then.

The phrase Zabaan e Urdu e Mu’alla can be shortened to Zabaan e Urdu, which according to the grammatical rule can be translated in two ways – the language of Urdu, or the Urdu language.

So the connotation of the word Urdu changes from the name of a place, to the name of a language. (Also seen in Dehli/Dehlavi, Bangal/Bangla and so on.)

The connotations of the words Hindi and Urdu today are fairly recent constructs, and products of the anti-colonial era. Although these names Hindi and Urdu were used to refer to the lingua franca of north India in the 19th century, the distinctions were not very apparent. Similarly, the Hindi used in schools and government today too is a modern construct, and sounds markedly different from any literature dating back further than this era.

Early in that century the British colonial administration replaced Persian with English as the language of higher levels of administration in parts of the north, while the lower administrative levels used primarily Hindustani written in the Nastaleeq script – or as we would call it today, Urdu.

This changed in the year 1900, when Hindustani written in the Nagari script, which we better know as Hindi today, was granted equal status by the British.

This resolution was passed thanks to the efforts of the Nagari Pracharini Sabha founded in 1893, whose members mainly belonged to propertied Hindu families. Besides promoting the Nagari script (mistakenly thought to have been the only script used for Sanskrit) the society’s activities also promoted literature reflecting a glorious Hindu past, essentially adopting Hindi as a Hindu language.

Concurrently, after this resolution was passed the Anjuman e Taraqqi e Urdu was set up in 1903 to promote the Urdu language and script. Most of its members of were propertied Muslims and Kayasths.

Use of the term Hindustani to refer to the spoken language of north India was popular and fairly common even in the first half of the 20th century. When the language of the Indian Constitution was to be decided in the assembly, R.V. Dhulekar moved an amendment in favour of Hindustani, stating that those who didn’t know Hindustani had no right to stay in India. Dhulekar said Hindustani not Hindi, which shows that Hindustani as a term was just as common as, if not more common than Hindi.

The Constituent Assembly finally decided that “the official language of the Union shall be Hindi in the Devanagari script”. Just the name of the language was not enough to convey the script to be used: the assembly felt that specifying which script to use for Hindi was imperative. This shows that the distinction between Hindi and Urdu even at that time was not as stark as it is today.

Through the passage of time, Hindustani language has been cleaved into two distinct forms – which are still largely mutually intelligible – primarily due to political forces especially after the Partition, and conscious efforts by the teachers, writers and speakers of both languages to distance themselves from what they believe to be “the Other”.

It is important that we recognise today that just like India, Pakistan and Bangladesh are essentially the same, with a shared history and culture, but were wilfully divided on the basis of politics, the same thing has also happened with Hindi and Urdu.

Arslan Jafri works as a Teaching Associate at Ahmedabad University

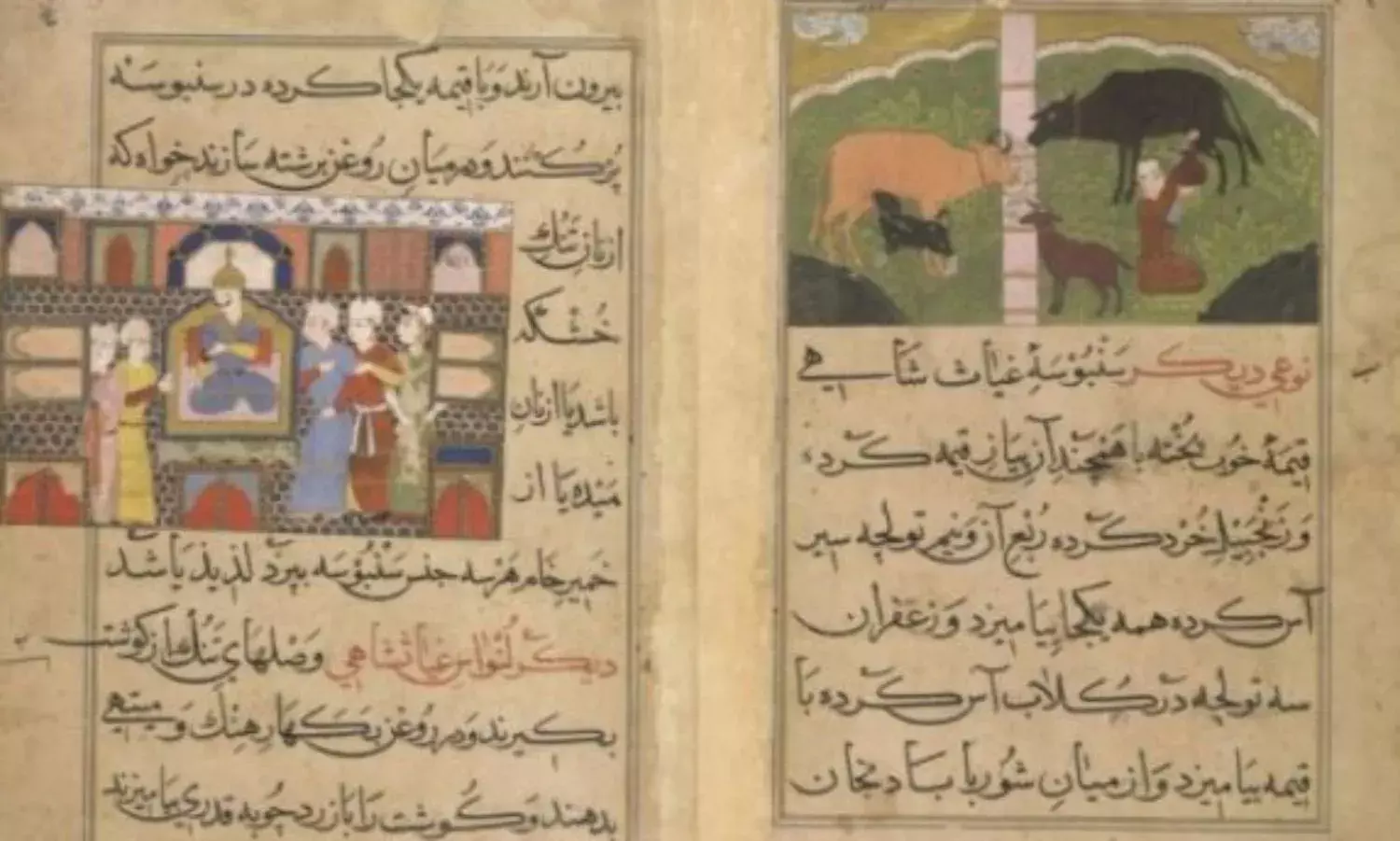

Cover: The Nimatnama from 15th century Malwa, composed in Urdu and Farsi in the Naskh (Arabic) script