Chamar Residents of Rasulpur Allege PDS Malpractice

Caste counts for fair PDS supply

SIWAN: “We pay more, yet we don’t get our due ration entitlements. The supply also comes late” say residents of Rasulpur in Siwan district, Bihar.

People here are exploited because of their caste, says Tiljhiri Kuanwar, 55. Most ration card holders in the village belong to the Chamar community, a Schedule Caste.

“According to government guidelines we should get 5 kg of wheat and rice per head in every family, but our distributor at the PDB [Public Distribution Booth] gives us only 4 kg per head,” says Kuanwar.

The Bihar government claims it has been providing 5 kilos of rice and a kilo of dal to each of the 1.68 crore ration cardholders in the state.

It also claims to have transferred Rs 1,000 to the Aadhaar-linked bank accounts of about 90 lakh ration cardholders since the pandemic.

Ranglal Manjhi, 62, said the PDS distributor Ramesh Singh when asked about the short supply said he kept one kilo as his share of the entitlements due to every member of a family.

Under the National Food Security Act a PDS ration card entitles you to 2 kg wheat and 3 kg rice for Rs 2 and Rs 3 per kilo respectively, per family member.

But people in Rasulpur say they pay an average of Rs 3 for wheat and Rs 3.50 for rice. Despite paying more, they do not get the foodgrains due to them.

Gogli Devi, 60, shares how “Last month I got weevil-damaged wheat and pulse. When I asked my distributor about it he said that is what he is getting from the government.”

But people in neighbouring villages were getting fine quality of wheat and pulse, she said.

“During Lalu’s government we had a red card, under the Nitish Kumar government we got coupons, and when the Jitanram Manjhi government came to power we got a new ration card,” says Mukhev Ram, 61.

He says it just conveys the message of rivalry among political parties.

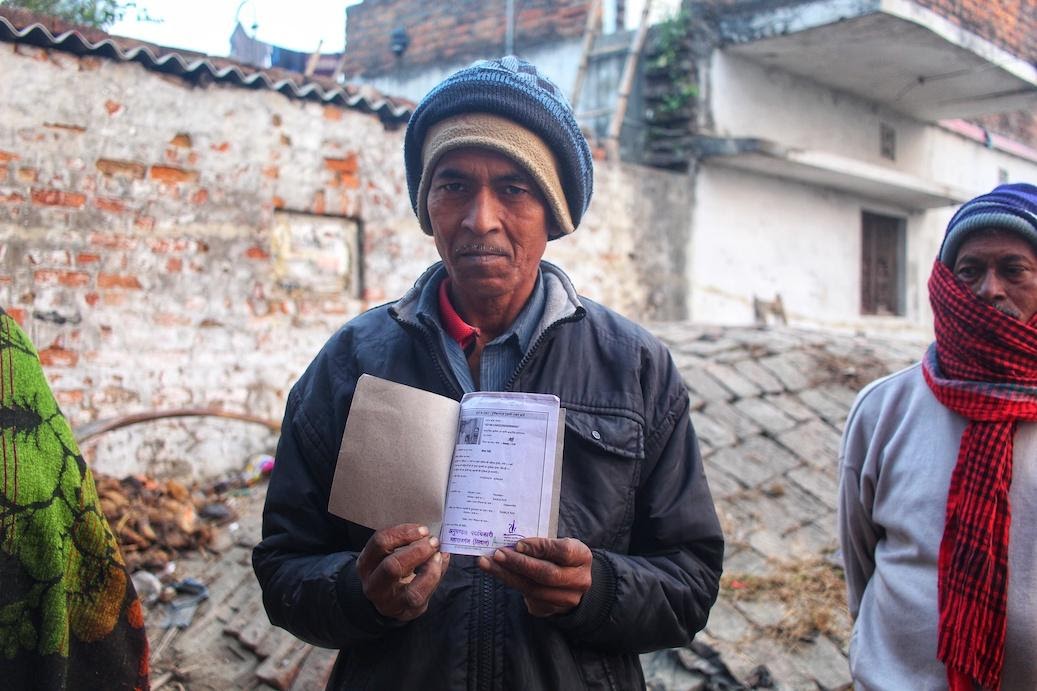

Mukhev Ram showing his wife’s ration card issued in 2019

“Each year we have to renew our ration card as it is valid only for a year. But we haven’t got the card this year. Our distributor said it was because of the pandemic,” says Ramjeevan Ram, 32.

India’s governments spend around 1% of GDP redistributing free or subsidised food to people with low incomes. It is the state’s largest redistributive measure both in terms of cost and the number of people entitled to it.

While many state governments have managed to curb leakages or corruption in the distribution system, its implementation remains especially poor in low-income regions.

The National Food Security Act is meant to provide subsidised food to 75% of rural and 50% of urban Indians. Despite overflowing foodgrain stocks, malnutrition remains stagnant in many states, including among children, and along some indicators it is rising.

Families in Bihar are among the country’s poorest on average, and a well working food redistribution program with curbs on leakage would provide the urgently needed health and safety net.

When Médecins sans Frontières set up camp in the 11 primary health centres in Darbhanga district to help treat Severe Acute Malnutrition among residents, it found that over 60% of the admittees were girls and 87% were from “the poorest or most vulnerable castes”.

The National Family Health Survey last year found that child mortality in Bihar was practically unchanged from five years before, at 56 per 1000 births, and child wasting or low weight for height had grown by 10%, to 23%. Severe wasting had grown by 25%, to nearly 9%.

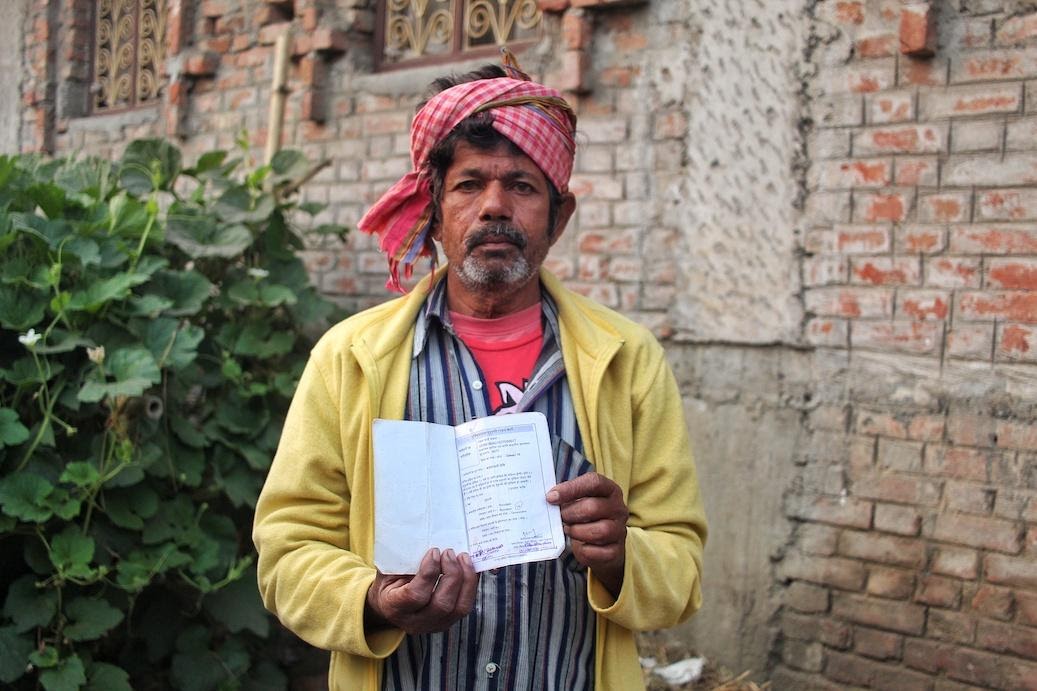

Ranglal Manjhi showing his ration card issued in 2019

In recent years the Bihar government claims to have computerised the PDS inventory network, installed GPS trackers on trucks, sent SMS alerts to recipients and improved vehicle tracking at the Bihar State Food Corporation base camp.

There are around 55,000 listed PDS retail outlets across 38 districts in Bihar, but despite the distress of the pandemic lockdowns and economic crash only about 47,000 outlets are currently functional.

Has the spillage tracking really worked on the ground level? Not according to Rasulpur residents.

Kalanti Devi, 61, shares how the PDS distributor Ramesh Singh told them the supply chain from the government’s side was slow because of the pandemic and economic pressure, which is why he was unable to provide them with free rations.

Ramesh Singh, 42, himself spoke of a “common practice in most of the villages here” of the persons concerned denying people free rations, and illegally selling the grains instead.

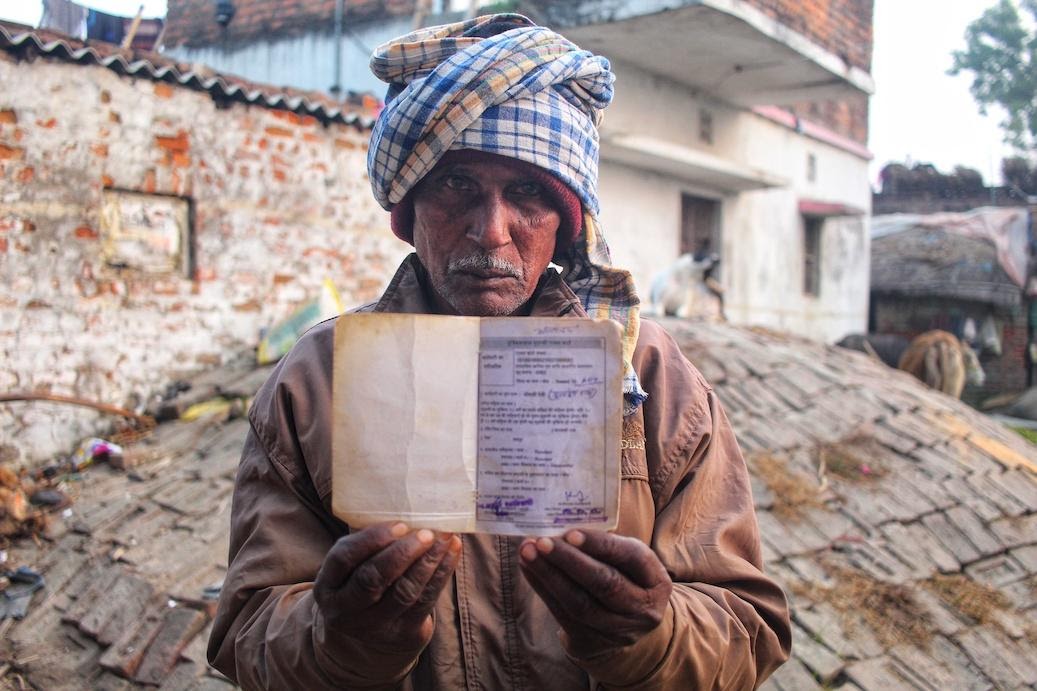

Tiljhiri Kuanwar showing his wife’s ration card issued in 2019

The rundown of families who qualify under the National Food Security Act for ‘Need’ or ‘Antyodaya’ cards has not been made public. So people do not know if they are entitled to subsidised food, or what their entitlement is.

The potential recipients were calculated based on ten-year-old Census figures and do not account for reverse migration or the families driven into destitution by the Covid emergency and government non-response.

Nonchalant, Rasulpur gram pradhan Pradeep Thakur (35) says:

“These things are common here as we all have to survive. This is nothing new. Before me other council leaders were doing it and now I am doing it because I am a part of the system. The circle officer, ward councilor, dealer and distributor at the Public Distribution Booth all take their share.”

Also read Bhopal’s Urban Adivasis Left to Struggle as Pandemic Rages on how civil society organisations and community groups have stepped in

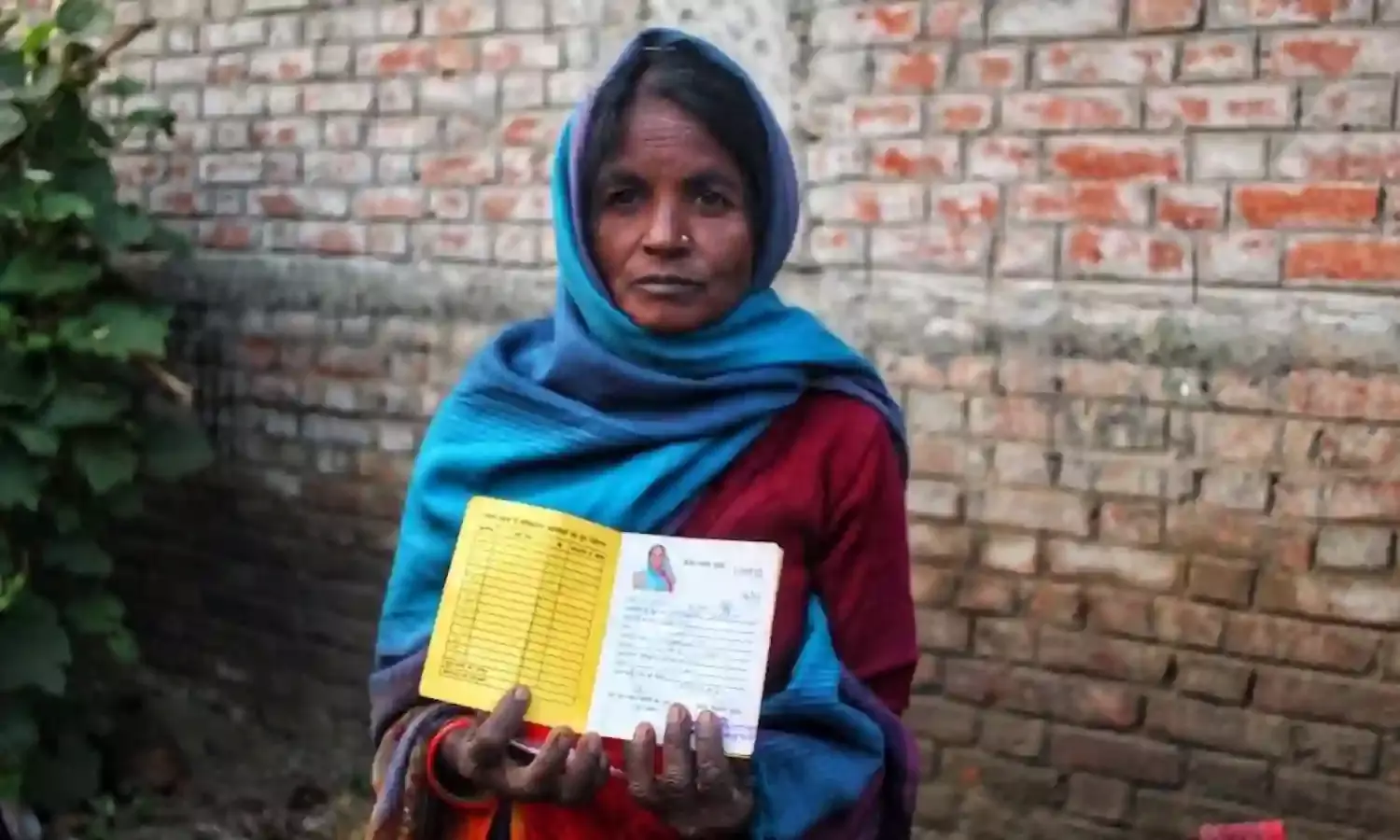

Kalanti Devi, 61 showing her ration card issued in 2019