This Can Only Happen In Lucknow

I could hardly see, but felt that everyone out there waited for something. I imagined people stand on one leg and then on the other, trying to yawn and to speak at the same time. Some stretched out their limbs to stroke an armpit while others furiously kneaded a crotch itching in sweat and together they slapped bugs that tried to feed on the exposed part of their respective body. Collectively drenched in copious quantities of perspiration, most in the the crowd dried the self furiously with the edge of the same long shirt worn by them. I was so sure, that those crowding the street were mostly men.

Considering that such a large number of people stood before me the atmosphere was unusually controlled. In the absence of fumes from traffic and noise of the day, the exchange between people was reduced to a monotonous, low hum in the hush of the night.

However a collective traveling voice filled with lament was heard coming closer..

I listened to a single beat mark time upon a kettledrum that made a gruff sound from a surface muffled tight with the skin of a goat and chained upon the abdomen of probably the most muscular person around.Accompanying the drum was a chorus of voices, of people surely dressed either in black kurtas or similar knee length tunics in green, and everyone in the group seemed to use the body as metronome, doing matam or repeatedly hitting the chest with the right hand in rhythm to melody. Some might use both hands one at a time to beat their breast in tune to what they repeated after the lead singer.

I could not see the chorus but as I concentrated some more I recognised the music it made. Then the lyrics bubbled out of memory and I found myself repeating in silence:

The waters are stormy,

The shore is not near.

Evil will have us forget,

And to dry our tear.

But we mourn Husain,

Our leader so dear.

We remember the heat,

And the dust of Karbala,

Where he battled without retreat,

Without water,

And without a drop of fear.

That moment it occurred to me that it must be the beginning of the month of Muharram. It has been ages since I last looked at the lunar calendar to check dates for performing Islamic rituals taught to me by my grandmother.

“Where have you been Bibi?

Where have you been…?

Oh my God, Oh! My God...”

Bano Bua had steered herself back from in between the crowd to return to me. She was striking her forehead repeatedly with the palm of one hand, looking out of sorts and muttering apologies under her breath.

“May God forgive this sinner…” she added throwing up her hands to reach the heavens.

Breathless and quite distressed Bano Bua looked here and there probably for a place to sit.

I held her arm and led her back into Munna Bhai’s Kebab Korner. Bano Bua collapsed on the same chair where she had happily sat gossiping and drinking tea only a while ago.

“The boys outside tell me that there is a big problem.”

“Bua please tell me what the problem is.”

“Bibi the Zaidi community that lives across the river is marching its procession towards Karbala in the old city reciting nohas and dirge and performing matam. This has never been done before. For hundreds of years Muharram is observed in the old city. Even those Muslims now living in newer neighbourhoods go to old Lucknow to observe Muharram”.

“It is alright Bua,” I felt my voice quiver.

“It seems like this is a small group of people that does not mean anyone any harm. And if they want to pass through here why not let them?” I consoled Bano Bua, craning my neck over the crowd, trying to get a glimpse of the procession of shia Muslims whose sorrowful rendition and rhythmic beats on the breast had crawled closer.

“What are you saying Bibi? That is not the only problem.”

“What then is the other problem?”

“Bibi there is a Hindu marriage procession on its way from the opposite direction, on the same path. Can you imagine what will happen once the two groups collide? Think of two trains rolling towards each other on the same track, bang!” Bano Bua slapped her hands together.

“People have been talking to both communities for days, I am told. But neither the Hindu merrymakers nor the Muslim mourners are willing to listen. Both insist that they have instructions from the divine to perform their respective ritual at the same appointed hour and not a minute before or a second after.

Now the crowd waits, wondering what to expect next?” Bano Bua continued, although much of what she said drowned in a thunderous fusion of the measured drumming of the distressed with the melody full of frenzy made by the marriage party.

This was a painful moment for all those who are proud to be descendants of the Ganga-Jamuni way of life. Spoon fed over centuries on customs as contradictory as the course followed by the two rivers that nevertheless converge happily at the holy site of sangam not far away from Lucknow, gangajamuni is always uttered in one single breath in Lucknow in lyrical support of the symbiotic confluence of both the Hindu and Muslim view of the world.

I went running out of Munna Bhai’s Kebab Korner to stand on the rim of what had become quite an epicenter. The listless sea of humanity was already beginning to swivel into a vivacious wave of commotion.

I felt Bano Bua lock her fingers into my own.

I heard Munna bhai shout instructions. I saw Naresh appear out of nowhere, hurrying towards us, carrying on his shoulder a long, wooden ladder. Teenaged boys ran back and forth on the pavement in excitement. A group of not more than five women, holding the hand of several small children and two of them carrying infants in the arms were moved away from under a street lamp and flocked closer to the kiosk by nervous voices giving orders in different directions at the same time.

Some energetic limbs helped Naresh to balance the ladder, made from two bamboo poles that were joined together with smaller sticks converted into steps, on the pavement to reach the roof of the kiosk.

Munna bhai hurried up to where Bano Bua stood hugging my arm. He looked at Bano Bua and then at me and shook his head as if he wished we had not been there. His eyes mirrored memories of millions of people already hacked to death by haters in the past.

In his panic at the thought of a bloodbath, Naresh dared to push Bano Bua towards the ladder making her slip and slide and she dragged me with her. The other women and children came to the roof top as well after me. The infants were immediately bounced back to the women by other helping hands behind them. Rising above the group of women, children and some elderly men, unknown to me, and who squatted on the floor of the rooftop, I tipped myself taller on the toes. When I stretched over to one side I clearly saw a scene that resembled a shot out of the popular film Monsoon Wedding.

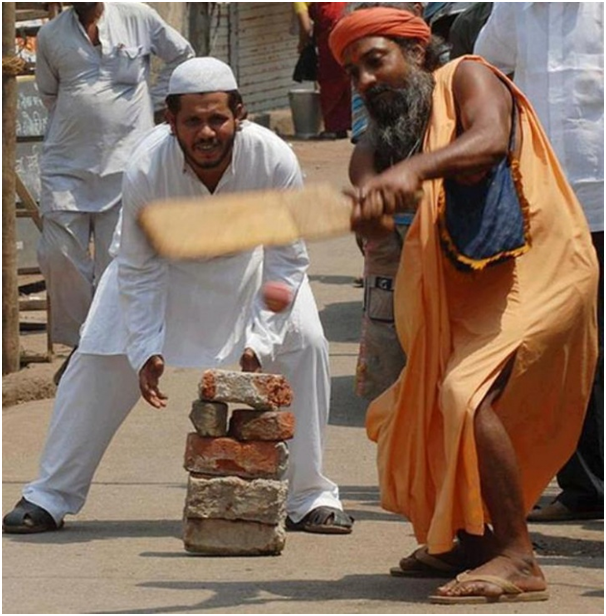

Men, women and children dressed in glittering accessories and bright clothes jerked their body forward to funky beats of party time tunes from the same film. In the middle of musicians and the dancers a majestic horse was seen to trot decked in equally dazzling drapes and in gold and silver streamers. The animal was led by a short figure sporting a big turban and it marshalled on closer to the front line of mourners on one side of the street with the happy humans hopping, skipping and jumping beside it.

The one astride the horse had to be the groom decorated in marriage finery, his face made invisible by a thick curtain stringed together with flowers and on his way to claim the bride waiting probably across the bridge.

I was no longer sure which side to look. I turned right and then to my left, able to enjoy both the pageant of gloom here and that of glad tidings there. I heard the soundtrack of modern cinema mingle with sombre singing by the shia. I smiled at one without feeling the need to frown at the other.

Waves of hurt wafted into lyrics of love, the clang of cymbals had little choice but to chorus along with beats quickened on breasts. There was no need for the vision to pendulate anymore as I saw contrary caravans, in front of me, let the other be. Both processions had refused to pause at the crossroad.

Instead, I saw them sail past each other like two ships in fair weather. I held my breath but in the next moment found myself breathing deeply again.

The crowd relaxed and paid little attention to the approaching sound of screeching sirens in flashy red that twirled atop several vehicles. People dispersed to make way for the platoon of police speeding upon the scene once again in chase of problems that had already been resolved.

“Lucknow is different. This can only happen in Lucknow,” I whispered to myself in great relief.

(An extract from a forthcoming book on Lucknow by Mehru Jaffer)