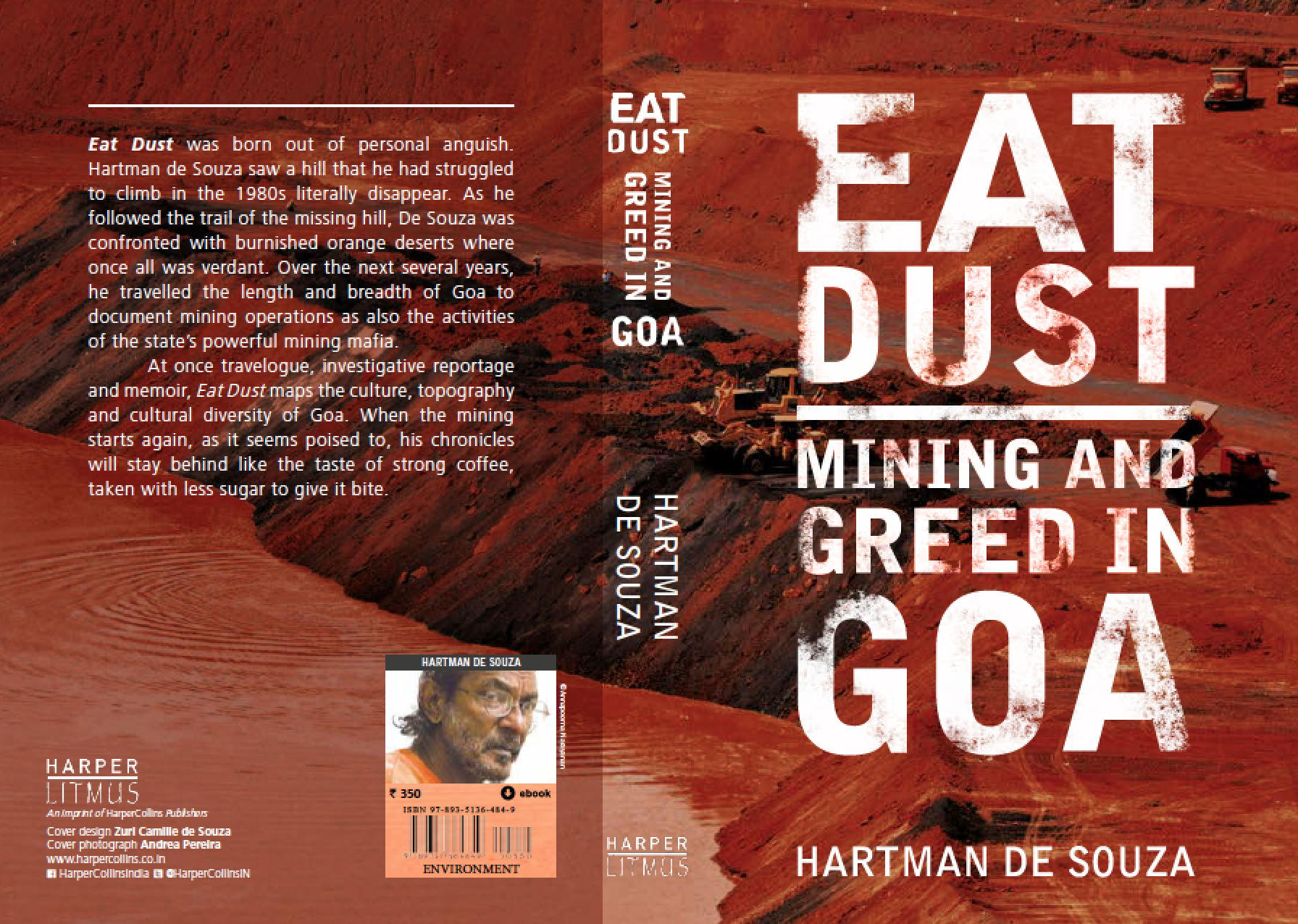

Eat Dust! Mining And Greed In Goa

Eat Dust, Mining and Greed in Goa written by writer, actor Hartman De Souza has recently been published by Harper Litmus. The Citizen is pleased to carry an excerpt from the book as below:

Shortly after the rains ended in 2008, before the mining season could start, I left for Pune to take up a short teaching assignment that ran till the academic break in Christmas that year. I admit that I ran away shamelessly. I would return, of course, but at that moment I desperately needed a break from having to see and hear about the mining every single weekday at close quarters.

By August 2008, the mines managers were openly boasting in Maina and Cawrem that they were going to start ramping up operations by many notches. Then the looting really took off. Soon, whenever they passed us, the managers in their company jeeps would slow to a crawl, roll their windows down, and push their heads out – smirking like cats sighting cream.

I began making notes for this chronicle as far back as 2006, wondering what mining would do to entire landscapes that I had cherished for years. I had long lost faith that the feeble opposition to mining in Goa would bear any kind of fruit.

I saw this chronicle as a factual blow-by-blow account of what actually happened on the ground – left behind like photographs in monochrome and sepia. Only when there was nothing left here, except the pockmarked ravages of open-cast mining, would everybody know how this part of Goa had been upended in a frenzy fuelled by greed.

I wanted to speak for the earth’s injured voice, but needed to run away from my own notes and the pictures in my mind. By early August 2008, they were beginning to eat circles in my head; I could even see them in my sleep. Those days, I felt like swinging at anyone who even suggested that the greed could be halted with our tactics and strategies. I may even have had a breakdown of sorts. Everyone noticed it too, which is what probably made me take off.

Regardless of what madness possessed me, I always knew I would keep this chronicle for the very last. Not like a dessert or iced liqueur-laced sorbet, but like a cup of bitter coffee on an empty stomach.

It was Justice Santosh Hegde, the fiery and conscientious peoples’ judge from Karnataka, who prevented this uncalled- for surprise by systematically deconstructing the extent of the fascist criminality at play in the once-flourishing mining empire of Bellary in Karnataka. We need to keep in mind that his first report on illegal mining in Karnataka was submitted to the government as far back as 18 December 2008.1 It opened a can of worms that would subsequently shame governments at the Centre as well as several states across party lines.

Justice Hegde handpicked his team of five officers based on their reliability, understanding of issues, and above all, courage.

Before he submitted his final 466-page report on 27 July 2011, indicting the then Karnataka chief minister, B.S. Yeddyurappa for illegal mining, to Governor H.R. Bhardwaj and Chief Secretary S.V. Ranganath, his team of five officers had scrutinised 400,000 documents and assessed 4 lakh bank accounts.2

It was his first report in 2008, however, that had started the tremors. Justice Hegde’s investigating team not only retrieved substantial evidence of skulduggery but also gave the government reason enough to think that that they had barely scratched the surface of Bellary’s mining scam.

It was unfortunate for the infamous Reddy brothers, who ruled Bellary in very much the same fashion as Goa’s mining families did here, that the man Justice Hegde chose as his chief investigating officer was U.V. Singh, Karnataka’s chief conservator of forests. He happened to be a man of integrity.

When U.V. Singh visited Bellary in 2009, he came across Somashekhara Reddy, MLA of the region and brother of the shrewder Janardhan. Somashekhara arrogantly asked Singh whether he had the permission of the minister in charge of Bellary to enter the district.3

‘As a citizen of India,’ Singh told him, ‘I do not require anybody’s permission to visit Bellary.’

In September 2011, speaking at a workshop at the International Centre in Goa after his retirement, Justice Hegde was quite clear that his team would have nailed everyone involved in the Bellary illegal mining scam. ‘Mere five officers scrutinized four lakh documents and assessed 4 lakh bank accounts. If we had got two more months, we would have literally nailed everyone involved in the Bellary illegal mining scam,’ he told the press as well.4

While he acknowledged that there were more people as good as the small band of officers who served him so well, equally, he said, the numbers on the other side were growing. In any case, he added,‘he was retired not tired’!

Justice Hegde had reason not to be cynical.

His more-than-capable prote?ge?, U.V. Singh, was promptly inducted into the investigating team of the Justice M.B. Shah Commission set up in November 2010, reluctantly instituted by a once-complicit Central government.5 Their hand had been forced. It was by then impossible to ignore the reports of large- scale illegal mining and the abject failure of several states and even the Centre to curb this disease from spreading.

It must, therefore, be said quite emphatically that it is the Justice M.B. Shah Commission’s investigations that finally saved Goa’s forests and water, and not – as may now easily seem to be the case – its home-grown, well-meaning, but eventually frustrated, judicial activism spearheaded by Dr Claude Alvares of the Goa Foundation.

In fact, as events on the ground unfolded from 2007 onwards, those who opposed mining were an amalgam of many creatures. The most influential in the Age of Greed were Goans (or those who had come to settle in Goa as the promised land) who allowed themselves to be wooed by the argument that industrialization was a necessity in Goa. They may have been incapable of seeing the virtues of plotting a distinct path for the state that would take it back to its remarkable social indicators of the late 1970s and early ’80s. They knew, perhaps, that their own personal success depended on the assertions of growth and development. They concocted situations where both sides could win. Let’s do this by consensus, they said, let’s decide how much environment must go if we are to ‘develop’.

It would not be unfair to say that the anti-mining lobby in Goa suffered from its fractured sense of ‘politics’. Those who ought to have known better chose the easy, comfortable route of launching an NGO or two and putting down a paper trail. They spurned the plea that the battle had to be fought away from the courts and on ground zero for it to make any headway at all.

What could we say when ‘anti-mining activists’ actually suggested in good faith that NGOs help the mining companies re-green some of their old mines?

But if they were to drive about 60 kilometres from Panjim, they would see how the rogues here weren’t even leaving any dumps on which they could plant trees like they were supposed to. They were digging their old, once-discarded pits, even those adjacent to the Selaulim dam – which provides drinking water to south Goa – in ever-widening concentric circles, leaving behind a bare carcass of earth. The ‘Grand Canyons of Goa’ as some put it.

By 2008, there was enough evidence that all was not well with Goa’s forests. But people consciously chose to look the other way, and why wouldn’t they, when Goa was on the move. By 2012, Goans topped the country’s per capita income index by taking home Rs 192,652 on an average per year. Bihar, languishing at the bottom, stood at a mere Rs 24,681 a year.6

It also helps to keep in mind that the strategies and tactics adopted by the anti-mining lobby in Goa were unilaterally arrived at, under the guise of a broad consensus. The loosely formed anti-mining group was never on the same page from the very first day. Beyond the sound and the fury, there appeared to be only one line of attack: petitions, petitions and more petitions filed against mines littered across the place.

If one was lucky, one could even attend a token protest meeting or send strings of group mails to a closed internet community. Meanwhile, precious time rolled by.

The legal precedent with mining-related cases as far back as the 1970s, as everyone knew well (or ought to have known), was what happened when the Dempo and Sesa Goa mines were beginning to expand their operations around Bicholim in north Goa.

Ramesh Gauns, the well-known anti-mining activist grew up and lives in this area. Speaking of the old days, he told us that it was common knowledge that aggrieved parties, whose rice fields and orchards were inundated with mining waste after the rains, would receive little help from the magistrates of the day. In a very patronising tone, they would just be told, ‘Arre baba, how can you fight these big companies with just one or two families in the village. Take their money and be happy. What else can you do after all?’

That kind of fatalism, historically, was the terrain on which the law would run its course on anything to do with mining in Goa. Even more antithetical to the belief that a struggle for the environment must emerge from the affected areas, and not be top-down, was made painfully obvious to us much later, and much before the ban on mining kicked in.

Dr Claude Alvares, the well-known director of the Goa Foundation, was the de facto leader of the anti-mining movement because of his long-standing expertise and experience, his passion, and – most importantly – his willingness to pursue matters (even though he was always badly strapped for funds and always severely understaffed). He remained at its helm until the day the Justice M.B. Shah Commission relieved him of his onerous responsibilities and forced the law to take a stand. In all fairness, the Goa Foundation had worked well within its self-imposed restrictions. A research report by it identified fifty- seven mining companies operating without consent under the Air and Water Acts. The Foundation then went on to file a writ petition against the Goa government asking the chief wildlife warden to issue wildlife clearances holding back the sanction.

Even more revealing, the Goa Foundation’s petition challenging the government’s order to the chief wildlife warden was held up because one of the judges refused to hear the matter because of his relationship with one of the mining companies.

It was also the Goa Foundation that tallied all the production of the mining companies and matched it with the data tabled in the assembly by then minister for mines Digambar Kamat. Not surprisingly, the Foundation discovered that forty-eight ‘legal’ mines had conveniently taken out 11 million tonnes extra. (It is another matter that on ground zero, we knew from 2006 itself that there was no distinction between ‘legal’ and ‘illegal’ when it came to the mining operations between Maina and Cawrem.) As the Foundation pointed out, this was in violation of the Environment Protection Act and the terms of consent under the Air and Water Act. These violations had, of course, gone to the Goa State Pollution Control Board – toothless in the Age of Greed.

It was only as late as 2012, more than four years into all the looting, that the Goa Foundation did to the mining industry what that industry did to the earth.

They went through approximately seventy-four reports of the monitoring committee, which visited several mines from 2008 and 2009, and sent these tabulated lists of violations to the chairman of the Public Accounts Committee, Manohar Parrikar (who was the leader of the opposition at that time) and to the Western Ghats Expert Panel. A little later, they withdrew all the cases filed by them in Goa’s courts, and moved the fight to the Supreme Court in Delhi.

In retrospect, it was those eighteen petitions filed by the Goa Foundation and a few more reports put forward by other legal collectives and concerned citizens, all well researched and meticulous, that provided the preliminary data for the Shah Commission. This, in turn, led to the Goa Foundation coming out with its own recent and totally damning report on illegal mining.

However, the courts themselves may not have been as seized of the matter as they have been of late.

For instance, the High Court of Bombay, Panjim Bench took eight years to pass an order in favour of the Goa Foundation’s first petition – filed in 1992 – which took the Goan expatriate Chowgule family, pioneers in the Goan mining industry, to court for setting up a beneficiary plant in a protected forest about 15 kilometres northeast in Maina.8 This is the same mine that they then leased to a raising contractor, who happened to be another politician, in the Age of Greed. That was when we caught them and lodged a complaint with Rajiv Yaduvanshi.

So, should one assume that the Chowgule family functioned ‘legally’ in that period of eight years? How is it, then, that they left in their wake a tract of land that today, regrettably, makes a deathly moonscape appear tame? For this too, there is photographic evidence.

Still, there are complexities that one cannot wish away.

One of the cases filed by the Goa Foundation pertained to a certain area between Maina and Cawrem but did not have its genesis on the ground. The petition was filed on behalf of the villagers of Maina and Cawrem but did not actually bwith them, or even allow them the space to actively support proceedings.

This was activism once removed. It consisted of carefully plotting the mining leases and companies owning them, then poring through documents and ‘laying down a paper trail’. There is no denying the importance of the work they were doing, of the groundwork they laid for future events – but it was work done in isolation. For all practical purposes, the Goa Foundation’s petition had been filed without consulting the villagers of Cawrem. The papers of the petition were not easily available to those affected either.

It was Claude Alvares who, well before the mining season of 2008 broke, arranged a meeting between the chief minister, Digambar Kamat, and the who’s who of the anti-mining lobby. Everybody had put aside ideological differences to be present.

As Cheryl did not want to see the former chief minister’s poker face, as inscrutable as a boiled potato on most days, she sent me instead. It was at this meeting, in full view of the twenty- five-strong anti-mining lobby, that the chief minister promised a blanket ban on mining until his cabinet’s Draft Mineral Policy was properly discussed. He said this the day before his Draft Mining Policy was made public, and it was something that eventually turned out to be embarrassingly pro-mining.

He made this promise in response to my angry statement to him that every single one of the mining operations in between Maina and Cawrem was illegal, and he was duty-bound to stop them and institute an investigation.

I was hushed, the matter played down, even the threat of confrontation denied. As with all meetings where activists or afflicted citizens meet the chief minister, far too much respect was accorded to the man. That he was accused of corruption many years later was small consolation to me. Sadly, many in the anti-mining group took his Draft Mineral Policy seriously, actually engaging with it instead of pressing for a blanket ban.

They all chose to ignore that Kamat’s words were just that.

(Hartman de Souza has a background in theatre, education and journalism. He has been associated with several theatre groups in the country and was, till September 2015, the artistic director of the Space Theatre Ensemble, Goa. )