Photographer Zacharie Rabehi On The Drought That Has "Brought Time To A Screeching Halt"

NEW DELHI: A few weeks ago, French photographer Zacharie Rabehi sent The Citizen a powerful image from a drought-hit village in Tamil Nadu. Within minutes of receiving the photograph, we commissioned Zacharie for an ambitious project that sought to tell the story of the massive drought crippling India. Over 330 million Indians are without access to water, with a heatwave exacerbating the already dire conditions.

Over the next few weeks, Zacharie - on assignment for The Citizen - travelled through some of the worst drought affected areas in the states of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Maharashtra. For the photo essay, Zacharie spoke to affected farmers who lined up every day to fill their water jugs from government provided tankers; went door-to-door, reaching out to families of farmers who were pushed to commit suicide; visited local government offices and factories that were left with no option but to shut down because of the lack of water; and spoke to migrants, forced to flee shanty housing conditions in big cities.

The final selection of images can be seen here.

(The original photograph submitted by Zacharie. Locals fill their jugs from a broken pipe in Anna Nagar, Thiruvennainallur district in Tamil Nadu).

Currently, Zacharie is in Mumbai -- a city that was the last leg of his journey as it is home to some of the largest camps for people fleeing the drought in Maharashtra. The Citizen caught up with him about his experience regarding this important assignment.

TC: What made you take up the drought assignment at this time, when leading Indian publications have been reluctant to send reporters into the field? Why did you think it was important?

ZR: I have always been interested in environmental issues and this crisis is something that is one way or another going to touch us all. People -- in cities in India or elsewhere in the world -- feel disconnected from the drought and think that it affects only people far away from them. This is mistaken thinking. The day that there is no one left in the field to produce the food we eat everyday, and when the cities are full of climatic refugees, it will be too late.

(A farmer in Tarihal village, Karnataka, where all four wells have dried up. Residents rely on government tankers to meet a small proportion of their daily water needs).

TC: You have travelled through three drought-ridden states. Which, in your view, is the most distressed or acute?

ZR: In every single place I visited, I could see people lining up to fill up their water jugs. The whole vegetation was dry, a lot of factories stopped functioning. In Mumbai the camps were filled above capacity and people stayed in squalid conditions with no sanitation and very little food to eat. It felt more like a generalised crisis than hotspots… There were many commonalities across the states, rather than differences.

(The crippling heatwave has hit the already drought prone area particularly hard. Crops, where visible, are dry and lifeless. Solapur area, Maharashtra).

TC: How did the local people react to you?

ZR: Not once in the journey did I meet someone who answered my questions in a dramatic or accentuated way. Even the families of the farmers who committed suicide maintained their composure. People were always fighting their way forward.

(Rama Chandra from Sawaleshwar in the Solapur District walks his goat herd on parched land).

TC: Was there any one particular story that moved you the most?

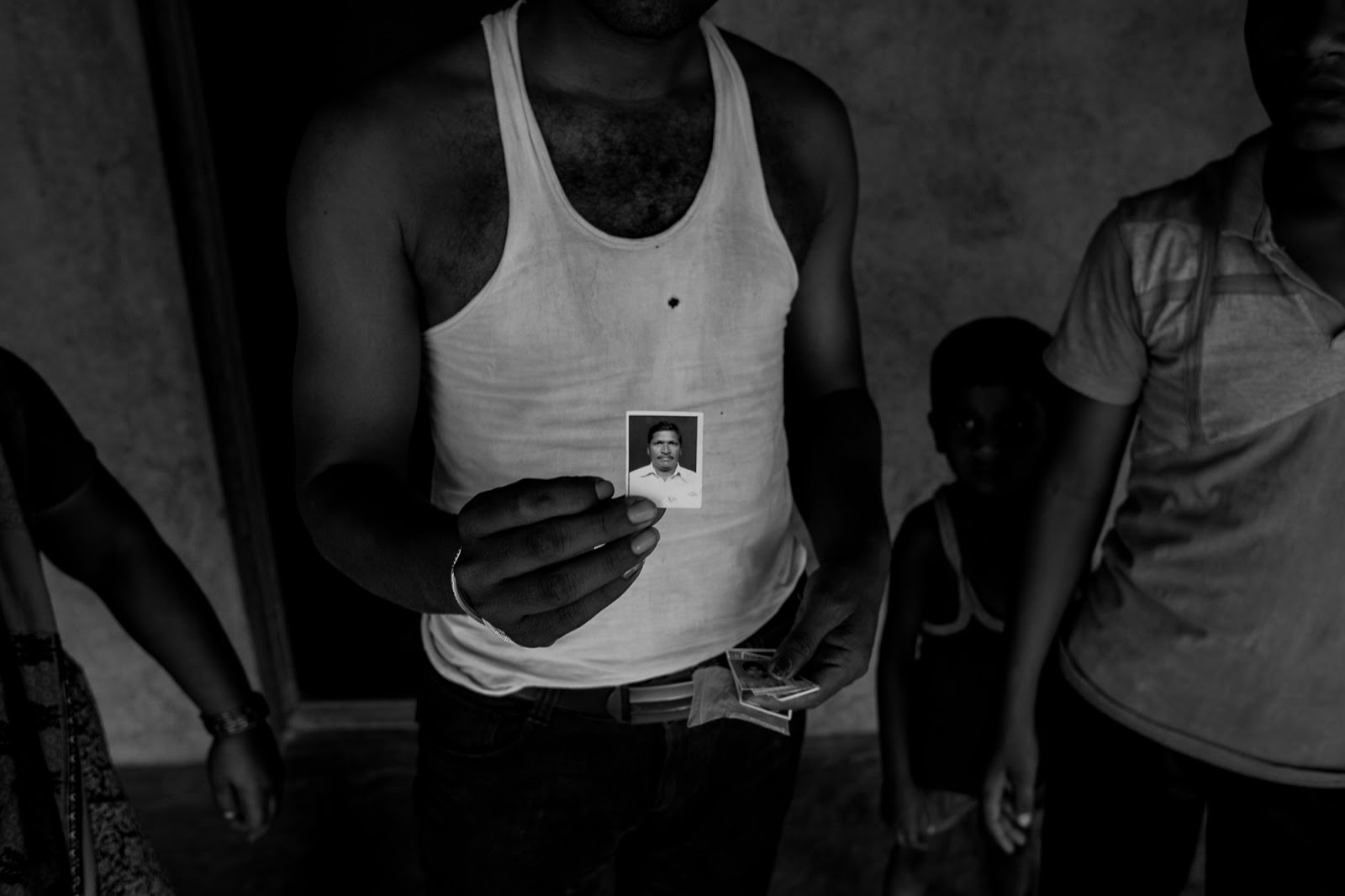

ZR: The story that touched me the most was of a family who used to live in a little tin house that was closed when I arrived. The man residing in it had committed suicide and his family had not been seen for weeks by the neighbour. It was the neighbour who let me in, and the second I walked in, it felt like time came screeching to a halt. Nothing had been moved since the people left. Clothes lay neatly folded on the shelves. A cooking stove and a statue of a God were the only other belongings. On the wall, portraits of the family members were hung. These portraits were in such stark contrast to the despair the pushed the man to suicide. The photo showed a happy father… who committed such a definitive, final act. Not being able to meet his family and ask questions so that I could get a sense of what happened left me feeling troubled.

(The family’s small tin house. A year ago, racked with debt, Limbajy Devaro Sabale from Khuneshwar walked 4km from the village and took his own life).

(Sabale committed suicide by hanging himself. The neighbour who opened the door, hasn't seen the wife and two sons in three months... He hopes that she made it to her relatives in Mumbai).

TC: Did you see any government presence in the affected areas? Were people getting sufficient help?

ZR: I went to the district office to get details of the families that had experienced a suicide and the officer in charge told me that out of the 11 such families in the area, only two received monetary help from the government. Other than that, some tanker trucks and trains carrying water circulate in villages offering a fraction of what’s needed. For the people who fled to the cities... except a few independent volunteers and NGOs, I haven’t seen any help offered.

(In the mohol administration office, the officer keeps a record of the 11 farmers who committed suicide in the past year. The total population of the area is 280,000 people).

TC: As a photographer, what were the challenges you faced regarding this particular assignment?

ZR: Because the people were so open and welcoming, it felt quite easy to work on this assignment. Of course, the heat and at times the difficulty in reaching places were things that slowed me down.

(A farmer and his buffaloes in Maharashtra).

TC: Of all the photographs you have taken as part of this assignment, can you select one that is most important to you?

ZR: There is this photo of a kid who is trying to find a way between the legs of ladies to get some vegetables during ration distribution at a Mumbai camp. The photo in itself tells a lot about the despair arising from this crisis.

(At a refugee camp in Mumbai, a child tries to make his way during ration distribution).

TC: Your previous photo essay for The Citizen also focused on a disaster -- the Nepal earthquake. Are disasters -- natural or manmade -- important to you as a story?

ZR: I didn't really go to Nepal to shoot the repercussion of the earthquake... but I went there and my photos show the badly managed redistribution of donations. All my essays for The Citizen are about man made mistakes that could be avoided if only greed wasn't an integral trait of human nature.

TC: You have spent some time in India. Tell us a little about why you often return to India, and what aspects of the country influence the kind of work you do?

ZR: I have spent a third of my life in India now... I still cannot understand why I keep coming back but there is some sort of connection I have with this country that is surely missing with where I was born.

(Main photo: Daji Babu Kamble took his own life about a year and a half ago, leaving behind his wife, three girls, one boy and his disabled mother).

(Zacharie Rabehi is a French photographer. See his work at www.zacharie.rabehi.com)