Criticism Is Okay, Uninformed Abuse Is Not: Gujarat Files

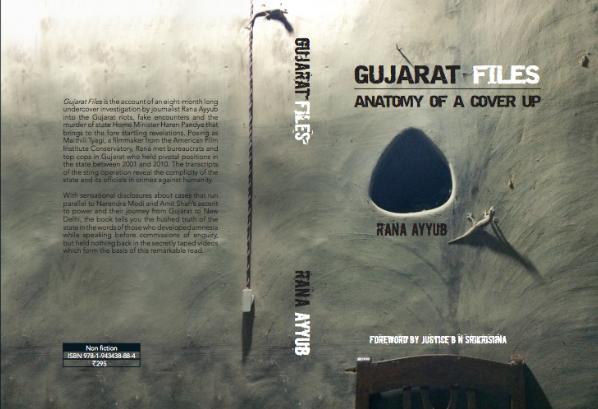

NEW DELHI: Journalism in India is a complicated, problematic assortment. Following the contentious, albeit ground-breaking revelations of the Panama Papers, Rana Ayyub and her book, Gujarat Files: Anatomy of A Cover Up, have established a marker in favour of a budding development: investigative journalism is thriving. It was not surprising, then, especially considering the vitiated political context of the country, that the glitterati of the capital flocked the launch event of Ayyub’s book. It was an event where political divides, which have become progressively prominent, made themselves known again. The book concerns itself with the 2002 Gujarat riots, ‘fake’ (or so they say) encounters, and the role of Prime Minister (then – Chief Minister) Narendra Modi, Amit Shah, and the state machinery of Gujarat in the same.

The narrative, which is breathlessly enunciated with little to no analysis, follows the exploits of Rana Ayyub, posing as Maithili Tyagi, an upper caste, Hindu filmmaker from the American Film Institute Conservatory in Los Angeles, with definite pro-RSS leanings. Aiding Maithili’s dangerous, ambitious, and brave investigations are Mike, a nineteen year old intern from France, Paani, Ayyub’s friend at the Nehru Foundation, Ahmedabad – where she stayed, and a host of friends and acquaintances who helped Maithili weave her intrepid social web. As Maithili moves from one personality to another, one finds her cajoling the most sensitive information from bureaucrats and state officials who comprised the eye of the storm. Indeed, Gujarat Files is an ode to courageous journalism – a variety that is of pertinence to India, given how corporate and political influence has embedded the media, leaving it in the sorry state that it is as a rather redundant paparazzi striving for the propagation of gossip that the nation now wants to know. We are, however, getting ahead of our story. Featured in Maithili’s striking narrative are recorded testimonials of senior officers like G.L. Singhal (Gujarat ATS chief in 2002), P.C. Pande (commissioner of police, Ahmedabad in 2002), G.C. Raigar (intelligence head of Gujarat in 2002), among others. In what were revelations made to a naïve, foreigner filmmaker, not much is withheld.

The testimonials point to, in no less than jarring terms, a giant loophole in Indian democracy that we now need to confront: executive abuse of power. What emerges in Ayyub’s narrative is a picture of the backing of the state machinery (heralded, of course, by then Gujarat Chief Minister Modi and his Home Minister Amit Shah) in orchestrating the Gujarat riots of 2002, as well as several fake encounters to fulfil the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) communal and political agenda. Whether it is the revelation of ministers fuelling and guiding frenzied mobs, bureaucrats being forced into silence with the threat of losing favour and morbid ‘transfers,’ or policemen having to ‘let Hindus kill’ or commit encounters they know are on flimsy ground, testimonial after testimonial is a statement of helplessness and the defeat of conscience to a regime that wouldn’t so much as hear voices of dissent. To this end, it also indicates the difficulty of judicial investigation, as orders are verbalised, never written, and communicated from the infamous apex through hierarchies of middlemen. Confessing at the outset that she, unlike a ‘good’ journalist, finds herself unable to master the art of detachment, Ayyub is extremely attached, perhaps too attached, to her agenda to let the monograph run any short of gripping.

Gujarat Files has opened to, especially for a self-published book, thunderous reviews. A brief exploration of the book on Flipkart and Amazon is revealing – scrawled across the section for ratings and comments is vile, diabolical abuse, ranging from ornate as ‘Rana Ayyub is an anti-Modi writer,’ ‘100% fictional book by a fake secular and paid journalist to malign the image of our prime minister,’ ‘Modi’s innocence has been proven and wholeheartedly welcomed by people across all religions, castes, and regions in India,’ to as succinct as ‘rubbish.’ This, of course, is not to lose sight of the rape and death threats that Rana Ayyub has received. What is particularly worrying, however, is that none of the abuse comes as informed, reasonable criticism rooted in even a cursory reading of the book.

As one filters the comments on what Amazon calls ‘verified purchase,’ meaning that the book has been purchased (and hopefully read) by the reviewer, the only comments and ratings that remain are positive, encouraging, and appreciative. This is emblematic of a seasoned, although recently heightened development in the configuration of democracy and dissent in the country – the employment of abuse, threat, sometimes actual violence, and vilification to suppress a voice that a certain kind of politics does not even want to hear. The ban on Wendy Doniger’s Hindus: An Alternative History, the controversy around Bipan Chandra’s book that refers to Bhagat Singh as a ‘revolutionary terrorist’ have made it clear, and we are getting all too used to it now – this not a regime that wants to listen. It only wants to be heard.

Much as disturbing as uninformed abuse is, the pertinence of informed criticism cannot be understated. Ayyub has not made available her tapings and recordings of the eminent personalities she claims to quote, although she has promised to hand them over, if asked. The narrative, as mentioned, is breathlessly, hurriedly enunciated, leaving considerable room for serious analysis.

Sting journalism is a debatable realm, and many, including journalists, have criticised its inherent deception, selective exposition, and weak factual basis. Gujarat Files, therefore, is an important intervention in India’s political context as well as in the discursive field of journalism whose findings and revelations need careful, thorough scrutiny. It is a book that should generate a labyrinth of conversations, most of which can be socially transformative. But is anyone willing to have them?

(“Gujarat Files” by Rana Ayyub (2016). 214 pages. Rs. 295).