Colder Than the Arctic Circle

THE THIRTY-FIVE MEN and women lying dead before me were each shot with a single bullet that made a muffled ‘pop’ as it passed through their heads. Only minutes earlier we were fellow passengers on the Kabul to Kandahar bus that was stopped near Ghazni by anti-Soviet mujahidin.

Thankfully, I survived, but my Afghan co-travellers became victims of a mujahidin bloodlust that started in 1980 and would last for several decades.

In theory the US-backed mujahidin, forerunners of today’s Taliban, were licensed to kill only those construed as being pro-communist or pro-Soviet. In practice the mujahidin were trigger-happy, keen to settle scores, or simply eliminate anyone who annoyed them, such as their innocent victims on that freezing afternoon in 1980.

Those dead men and women committed the mistake of holding on to newly issued red identity cards. Since red was the colour of communism, invoking memories of the Cold War slogan ‘Better dead than Red’, their fate was sealed. And each dead body seemed to drive temperatures even further below the minus 19 degrees that matched the cold of the Arctic Circle. It was the type of cold that I have never forgotten.

But let’s start at the beginning.

On 2 February 1980, friend and colleague Volkhard Windfuhr, a fellow reporter and the Cairo/Middle Eastcorrespondent of Der Spiegel, the German news magazine, suggested we travel together to Pakistan to cover mounting civilian protests in anticipation of the anniversary of the execution of President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. So, typewriters in hand, we flew from Cairo to Rawalpindi/Islamabad airport, stopping over briefly for a change of aircraft in Dubai. Bhutto’s daughter, Benazir, was a friend from my Oxford days and I wondered if it might be possible to meet her. But she was under house arrest at the time and any hope of meeting her never materialized.

The next three days were spent in the company of some two dozen other foreign correspondents witnessing the deadly Islamabad and Rawalpindi street battles between army, police and civilian demonstrators. Many died, but in truth my coverage for The Observer, which only made page eleven, was good but no better than anyone else’s. The one major difference was that I was able to converse in Urdu with the demonstrators, so it was possible to get a real feel for the pro-Bhutto passions and the real hatred for the military dictator who had ousted and then hanged him.

It so happened that the looming anniversary of Bhutto’s execution was only one of two major international stories. The front page that Sunday was actually dominated by coverage of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, which had started weeks earlier. World media attention was focused on what the Soviets would do next. Was the takeover of Afghanistan part of a more sinister plan to take control of a warm water port and, if so, would that give Moscow an edge over Washington? Would Pakistan be destabilized, would the Soviets seek military help from their traditional ally, India, who would be only too pleased to participate in a pincer movement squeezing the life out of Pakistan?

So it was hardly surprising that hours before I was due to return to my apartment in Cairo, I had a call from The Observer’s foreign editor asking if I would stop over in Kabul for a few days. The paper’s staff correspondent, who had been following the Afghan story, had just left. Seeing as I was less than an hour’s flight away, I had been earmarked as his replacement. For me excitement mounted as I took possession of a large slab of US dollars wired to me from London via the post office in Rawalpindi.

Leaving Volkhard back in Islamabad, I took the first available Pakistan International Airlines flight arriving early afternoon in Kabul. Most of the foreign press were staying at the Intercontinental where I also checked in, swelling their ranks.

Getting reliable information proved more than difficult. The American ambassador had been assassinated the previous year and after the invasion most foreign embassies had shut down or drastically reduced their staff. One of the exceptions was the Indian embassy headed by Dr Jaskar Singh Teja as ambassador, who invited me to his home for a briefing over drinks. We had never met before, but I was counting on how our common Indian ethnic background might at least secure me a ten-minute interview. The calculation worked. Teja himself turned out to be a shrewd, calm, collected professional diplomat. His nervous wife was a chain smoker who kept interrupting our conversation by saying, ‘Be careful, be careful.’

Although the fact that the Soviets had invaded was indisputable, its reality on the ground was still blurred. My first dinner in the hotel was at the roof top restaurant where a Filipino band, seemingly oblivious to the audible gunfire, continued playing their entire repertoire of yesterday’s popmusic, including, two months too late, Bing Crosby’s ‘I’m Dreaming of a White Christmas’.

That may have gone into my copy at the time as a throwaway line, but the news angle the following morning was dominated by references to more significant pop music icons, the Beatles.

They featured in the BBC’s breakfast radio news bulletin that led with references to a front page story in The Times written by Robert Fisk who had just returned from the Salang Pass in the northern part of the country where he had conducted face-to-face interviews with Soviet officers. An English-speaking colonel, apparently delighted to speak to a British reporter, summed up the Soviet Union’s international isolation by asking if the Beatles were still alive. This was 1980.

Every reporter craves the front page and to my untrained eye this was the most significant international crisis in decades, seemingly even more important than any previous Cold War standoff. So getting it right with accurate, in-depth reportage mattered more than visiting Kabul’s famous Chikan Street for carpets, or the equally famous hillside cemetery that has the grave of Babur, the founder emperor of the Mughul dynasty that ruled South Asia for 500 years.

Fisk’s story with its brilliant new angle about the Soviet Bear’s advance, this time across the Afghan border rather than Hungary and Czechoslovakia, left me jealous and, perhaps more tellingly, gave me a renewed sense of motivation. When I ran into him that day in the lobby of the Intercon, I asked him straight out, ‘Did you make it up?’ Belligerent, he countered, ‘You’re so lazy, why don’t you go and see for yourself. All any of you do is stay in the safety of the hotel.’

At his suggestion I made for the bus station in central Kabul to see how close I could get to the frontline. Dressed in a shirt, tie, dark blue blazer and green Barbour jacket, I thought I’d spend a few hours in the Afghan countryside watching Soviet soldiers advance towards the capital before returning to Kabul. But unbeknownst to me, the rusting, overcrowded bus, the type that makes you feel nauseous because of the diesel fumes spewing through the floor, was a non-stop service to the city of Kandahar, at least twelve hours away.

Those diesel fumes probably helped knock me out because ten minutes after we left the terminal I was sleeping like a baby on the very last row of seats at the back of the bus I woke up as I was thrown forward when the bus suddenly stopped. Within seconds came the unmistakeable sound of gunfire; a kind of sharp pop, pop noise. We were under attack from a group of so-called Islamic revolutionaries, the mujahidin, armed and paid for by the CIA. They had stopped the bus in what seemed to be a ravine. On my right-hand side the road seemed to meet the mountains. On the left was a valley.

It turned out the fighters who’d stopped us were under the command of a controversial student leader-turnedpolitician and Islamic fundamentalist, Gulbuddin Hikmatyar, who later briefly served as prime minister, and was famed at the time for throwing acid at a female student who dared to remove her veil at the campus of Kabul University. Today’s Islamic zealots from the likes of the ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham) would be proud of him.

Two of the fighters, dressed in what became famous as 1990s-style Taliban high fashion, loose shirts, baggy trousers and turbans, boarded the bus and spoke to the driver. He was ordered off the bus and didn’t reappear. The windows were steeped in condensation, so to begin with it was not possible to see outside without attracting attention. I made a tiny hole in my fogged window on the right side of the bus from where I could see the driver arguing heatedly with the fighters, then he just seemed to vanish.

Five minutes later the two fighters got back on the bus and ordered the first of the passengers off. He was a craggyfaced man in his late forties and, like the driver he got off on the right-hand side. Like the driver, he too seemed to argue with the fighters, until one of his interrogators took out a pistol and shot him. Bang, he was dead.

Those of us who were on the right-hand side of the bus could see what had happened, those on the left had no idea about what was going on until one of the passengers on the right leant across and said something in Pushtu. It was still not clear at that point that our ambushers were intent on killing all the unarmed civilians on this bus.

The gang were demanding to see ID cards. So all those carrying red-coloured documents issued by the communist government in Kabul (the driver and every passenger, except for me) were shot in the head at two- or three-minute intervals.

The pattern was the same. Each passenger disembarked from the front right-hand side. There was a brief conversation, although looking back it was more like an interrogation. Then pop! As the killing got underway, a sense of fear swept throughout the bus. The remaining passengers didn’t speak, in fact there was an eerie silence. Maybe they were, just like me, wondering if they could talk their way out of a nearcertain death.

My focus was on trying to keep warm by rubbing my hands and wiggling my toes, while at the same time thinking of a strategy for surviving the mass execution process that was underway. It was so clinical. I remember wondering what kind of story I would write if I survived? What would my intro be? How would I introduce the personal element? Although I didn’t speak their language, I felt a bond with my fellow passengers. We were in effect the passersby of history, caught up in a much bigger story than ourselves.

Squeezed between my professional and personal responses, I caught myself thinking of the stories I’d been told about the Second World War and what had happened to the Jews in places like Auschwitz. They were innocents like us, rounded up and killed in vastly greater numbers to satisfy the bloodlust and political agendas of the lunatics who had conquered their countries and thought they were entitled to take charge of the destinies of other human beings.

The mind plays funny tricks at times like this. One image that kept flashing through my mind was of the striped pyjamas that the Jews wore in their concentration camps. But we are dressed in ordinary civilian clothes, I kept thinking to myself, so how will the rest of the world know we have been executed? If I am killed will someone light a candle for me? Another thought that crossed my mind at the time was whether animals have souls like human beings and, if so, would I meet up with the soul of the baby goat my parents once adopted, or the dogs we had when I was a child growing up in New Delhi? One of the dogs was a baby alsatian called Tiger who was killed in a road accident. The other two were spaniels, Biggles and Minus, and they each lived to a respectable dog age.

At one point I remember thinking to myself, ‘Behave yourself, dogs are considered unclean in Islamic culture. If you mention Tiger, Biggles or Minus, they will not hesitate in killing you.’ Then for a brief moment I was angry with myself: stupid little Indian, one half told the other, who asked you to get involved in reporting a war that has nothing to do with you?

Images of my parents and stories about them or by them kept crisscrossing my mind. One of my mother’s friends, some twenty years earlier, was the wife of the then South Vietnamese consul general in Delhi, a former Saigon University professor called Do Vang Ly. His wife, Tuit, was often at our house, learning to cook chicken curry and other dishes—Kashmiri style—from my mother. I remember her laughing and telling my mother how popular she would be when she returned to Saigon as the only Vietnamese housewife with a repertoire of Kashmiri dishes under her belt.

As I sat in the back of that freezing bus, I remembered other stories of the Second World War that my father had recounted years earlier when he served under Field Marshall Slim in Burma, before being reassigned to Iraq and Egypt.

Death had toyed with him as well all those many years earlier. One of his grisly stories was about the American officer with whom he had been billeted in Baghdad. Early one morning father was awoken by the sound of a bullet fired at close range. Still dressed in his pyjamas, the American officer, whose name I was never told, had walked up to his shaving mirror, taken out his army-issue pistol and shot himself dead. There was no suicide note, no reason was ever discovered.

While these stories and memories from my childhood flashed before me, another part of my brain recorded my fellow bus passengers disembarking one by one. They were adult men and women, no children, mostly middle-aged and some elderly. There had been no opportunity to interact with them as we left Kabul and now it was too late. I didn’t know any of their names, or what families they had left behind. I saw them standing outside against the backdrop of the lunar landscape, grey rocks and boulders on either side of the road, nothing green, nothing white or yellow, just a monotonous, unrelenting grey. True, I heard one or two shouts before they were shot, but all died without a struggle. At this point, as the nausea started to rise, I wondered how I would cope if a sudden darkness descended on me.

As I was on the last seat, I was also the last passenger to leave the bus. From the steps I could make out a large pile of lifeless bodies. Some of the men’s brightly coloured red and blue turbans seemed to have unravelled close to them. These were my fellow passengers and their senseless murders haunt me to this day. I still remember the terror that consumed me, the numb fear that made it difficult to breathe. I could hear my heart beating like a drum. My body was rigid, but my mind was asking a million questions. How many times would they shoot me? Would I feel it? One thought that kept going through my mind was whether they would kill me and burn my body beyond all recognition. In that case how could my charred corpse ever be recognized and how would news of my death be passed on to the newspaper, let alone to my parents living at the time in Chandigarh back in India. If my body was ever discovered, would it be taken to London or New Delhi? Or would it just be buried in a shallow pit beneath a rubble of those ever-grey stones?

By now it was my turn to step off the bus, still freezing cold and trying not to look at the bodies lying only metres away. I stumbled, knocking my big toe against a stone.

There were three men facing me. As I showed them my blue and gold British passport, the leader of the group— pistol in hand—hit me across the face.

‘British journalist,’ I shouted, trembling, wiping away the blood oozing from the side of my mouth, before he hit me several more times. I didn’t speak Pushtu, but it was obvious that they were hostile. One of the words they repeated and I recognized, common to Arabic, Urdu and Pushtu, was ‘jasoos’ or spy. One of the three, a chubby 25-year-old, spoke a few words of English.

He was the one who stood next to me while the others set fire to the bus; how, I’m not sure, I was still dazed and too shocked that I was still alive to take in what was happening. Chubby was also the one who shouted ‘come, run’ a few minutes later as the smoke from the bus curled into the sky.

My memory of what happened next is hazy. I remember feeling stupefied as the gang beckoned me. Stumbling and running across that lunar scape of empty, frozen fields, I followed them. There was no choice. To lag behind meant death, if not from bullets then almost certainly from the subzero temperatures. We must have run off-and-on for three or four days, sheltering at night in remote villages, hoping we wouldn’t be attacked by Soviet helicopters.

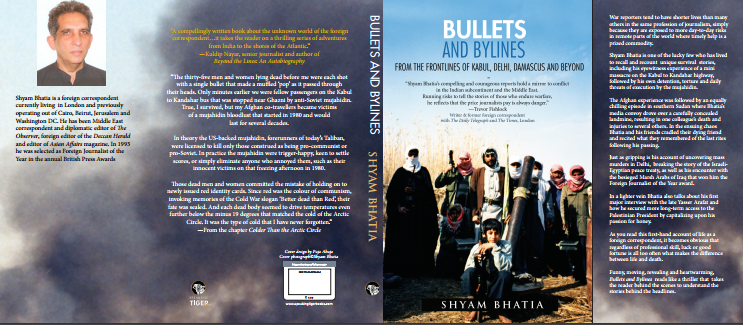

(A short extract from the book Bullets & Bylines: From the Frontiers of Kabul, Delhi, Damascus and Beyond, by Shyam Bhatia that has been released recently. Published by Speaking Tiger)