Nihalani's Tribute to Mahasweta Devi Demolishes the 'Myth' Of The Mother on a Pedestal

KOLKATA: Mother of 1084, an immortal novelette by Mahasweta Devi, stands completely in context within the prevailing socio-political ambience that sustains in India today where the value of a cow is held over and above the value of human life. Yet, this is the same cow that is worshipped as “Mother” by hard-core cow-saving squads on the one hand, and milked mercilessly by starving the same cow’s young ones on the other.

We are going through a time when little girls are gang-raped and killed and the rapists wander around freely; where a middle-aged man is beaten to death on the mere suspicion that he had stored beef in his refrigerator.

Within this ambience, Mahasweta Devi as a writer stands out for having predicted this time and situation through her stories on the Mundas, the Hos, the Shabars and the Oraons – tribes of India she held much above the mainstream. But are the Mundas and the Hos only ones who are oppressed, tortured, humiliated and marginalised and left to die without justice? What about innocent residents of a metro city who are crushed under an under-construction flyover in a crowded area because the materials and the construction were below the standards demanded?

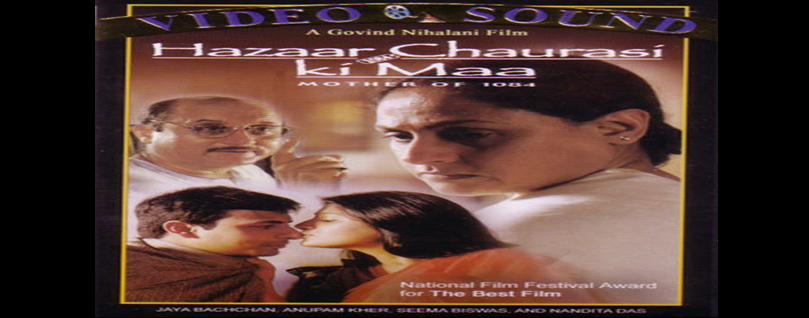

Mahasweta Devi created a watershed in Bengali creative fiction in general and her own writing in particular, when she wrote Hajar Churashir Ma (translated in Hindi for the film as Hazaar Chaurasi ki Maa), in 1973. For the first time, she turned from a personalised, middle-class setting to focus on the Naxalite movement in West Bengal. She chose as her subject, the impact of the Naxalite movement on an elitist, upper-middle-class, urban Bengali family, upon the violent death of the youngest child. Sujata Chatterjee (Jaya Bachchan), the protagonist of the story is a wife and mother in her forties, who works in a bank. Her work is kept invisible because it is not linked to economic independence.

It is more an expression of protest and self-assertion against her husband who is a debauche and a corrupt man. This is the only way she can express her individuality while she functions within the paradigms of the same patriarchy she condemns, without disturbing the status quo of marriage and family life.

Sujata could identify with many urban mothers in their forties and fifties, who find work outside the home as the only exit point from a trapped relationship that sucks them into a vortex of constant camouflage. Nearly 25 years after the novel was written, Govind Nihalani decided to filmise the novel, making minor departures towards the climax to bring in the contemporary perspective, and to create a kind of objective distance from the incidents in the story.

Sujata's story differs from other mothers by virtue of the socio-political setting the novel is positioned in. The novel records a day a day in her life, exactly a year after Brati was killed on his 21st birthday. Visiting the house from where Brati had been dragged out and killed by the goons of the Ruling Party, supported by the police. Talking to the woman whose son also died in the same encounter, who offered shelter for the guerillas to hide, talking to the Naxalite girl who Brati was in love with and who has been partially blinded by police torture but still swears by the cause, the mother of corpse number 1084 discovers for herself, the enormous spread of the power she had so long identified with her corrupt and overbearing husband alone.

The death of her son forms the catharsis in her life, setting her on to a journey of self-introspection and questioning, which widens the sphere of her knowledge about the power of patriarchal exploitation and its absolute control over women, as wives, and even as mothers. It is also a journey into the life of her son, who she thought she knew well, but really did not. She discovers that even when he had come forward to take her into confidence, she had shrugged it off with amused tolerance, as if he had been joking.

Though Nihalani's film remains loyal to the spirit and the textual content of the story, Hazaar Chaurasi ki Maa, the film, weaves a structure very different from the novel. The film opens with a woman stepping out of a taxi into a nursing home with a suitcase, all by herself, to deliver a baby. The delivery or the baby is not shown though, because the camera immediately cuts into the bedroom of a middle-aged couple, with Sujata suffering from stomach cramps, reaching out to wash the mandatory pill down with the glass of water. The telephone rings, punctuating the ominous silence of the night that permeates the well-appointed house. The disoriented voice across the line asks her to come to the prison morgue to identify the body of her son. She arrives, all alone, and identifies the bullet-ridden body of Brati which has a number tagged on to a toe : 1084.

She is the lone witness and implementer of his last rites. The reaction of the rest of the family to the tragedy is totally unexpected. Her husband uses his influence and contacts to cut out Brati's name from all media reportage about the deaths. No one mentions his name either, because a Naxalite in the family, be it the son, even after his death, invests the family name with a stigma they can do without. She invokes the family's wrath for questioning this, in her own silent way. Sujata is haunted by memories of her son, and reinterpets what he tried to tell her so many times, now, in retrospect.

The mother of the other boy (beautifully enacted by Seema Biswas) offers another shock. Though she is illiterate, poor and oppressed, unlike Sujata, she was never distanced from what her son and his friends were into. Sujata also meets Nandini, Brati's girlfriend, still sticks by the cause of a movement that is almost grounded by betrayals from within and torture from without. The sudden police raid of Brati's room is yet another point of shock for Sujata. Her silent face expresses her tragic feeling of her son being killed all over again.

The film meanders along, ever so slowly and somewhat repetitively, like a silent dialogue between Sujata and her dead son, through letters she pens to him every day. Her coping with her tragedy is constructive because in the end, she celebrates his birthday but not his death, both of which happened to fall on the same day. For her, the Bratis of this world can never die, they can only be born everyday. In a party sequence to announce the engagement of the younger daughter, Sujata faints as her appendicitis bursts. At this point, Nihalani's camera cuts to the same nursing home where Brati was born and shows a much younger Sujata nurturing the infant Brati by her side. It is as if her understanding of Brati is complete.

The film should have ideally ended here. But since Nihalani wished to invest it with a contemporary ambience, in a flash forward, we are suddenly brought to 1997, showing an aged Sujata running a documentation centre of human rights, with her mellowed husband offering her support. But there is yet another killing in broad daylight, of one of Brati's peers in the movement, who still works with the tribals in the villages. Sujata manages to catch one of the killers while the other flees in the car they had driven in. The film ends with Sujata penning yet another letter to Brati on his birthday. The flashforward is suddenly thrust on an unsuspecting audience that has just warmed up to the quiet, subtle voice of protest that runs like an undercurrent throughout the film. It is the only discordant note in an otherwise well-structured film.

When the film opens, Sujata is an introvert, prone to long, dark silences, but when the film ends, she has opened up, flowered into a persona that merges the mother with the humanist, the personal with the political. The party scene is reminiscent of Nihalani's early film Party, since the common thread running between the two parties is the subtle, slow and steady uncovering of the different masks urban people never tire of wearing. There are digs made at so-called Leftist commitment that is almost always, after the act, made in both films.

The treatment is so skilful that it never evolves into a cliche. Except for the fact that Jaya Bachchan’s screen image, as hers is a very known and much-admired face within a non-glamorous build-up, overshadows the character of Sujata because we are constantly seeing Jaya and not Sujata through the film. Joy Sengupta in a debut role as Brati is outstanding through the constant glimmer of something starry in his eyes, his sharp intelligence that shines through and his low-key bonding with his confused mother.

Earlier films, such as Jabbar Patel's Subah and Rituparno Ghosh's Unishe April already explored the rupturing of the relationship between a mother and her child. Both these films. including Aparna Sen's Parama, exposed the cruelty of patriarchy's insistence on punishing the mother who deviates from her designated positioning.

Hazaar Chaurasi ki Maa takes this critique one step forward in demolishing the myth of the mother by taking her off the fictitious pedestal she has been placed on by patriarchy. In fact, the mother is drawn back into becoming a human being per se, a woman with a commitment triggered off by the violent death of a young son.