Fonseca the 'Bypassed Genius'

Fonseca takes the reader on a visual journey

There are many stories you will read in this book. The story of new India, of Goa, of Christianity in India, of art, role of modernism, of new identities, but the most moving will be the tragic story of masters of Indian art who remain forgotten until they are found.

And when they are found, their art opens a Pandora's box of history and symbols that in many subtle but significant ways tell a story of an Indian.

The book Fonseca published in August 2022 by Gerard da Cunha and Architecture Autonomous is an ode to the brilliance of a Master, Angelo da Fonseca. Writer Délio Mendonça, takes us on a visual journey to truly understand the academic brilliance of Fonseca.

Fonseca, was a visual artist and painter from early modern India with a strong, consistent visual language, imbibing regional identities with international purpose. He was a man on a mission, and the mission was the way he led his life.

Idea Vs Art

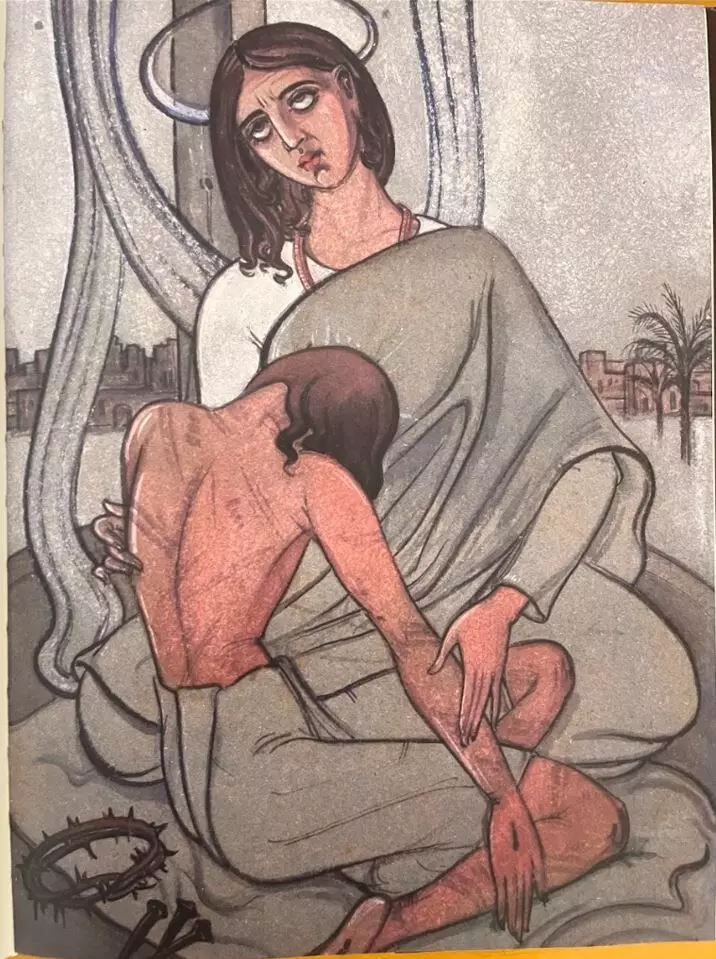

Fonseca has been called a 'Bypassed Genius' by the author, because he challenged Christian art assumptions and reinterpreted them for an Indian context. In the beginning of the 20th Century the Church was rejecting modernism, it was Fonseca, a deeply religious man himself, who asked the question : "Why could not the Catholic church find herself at home in India, since she is really Catholic, i.e. universal, Indian in India as she is European in Europe"?

He may not have been the first to do so but the book reveals he could have been the most significant artist who was painting Christian themes not for study and appreciation but for the devout. To help them forge a deeper recognisable connection with their faith.

However, his art never found a home in the religious landscape of India, and remained hidden in the academic world despite his trials.

It has been through the determination of his widow Ivy da Fonseca, that Fonseca's art found its way into the world through this book. While this book examines and suggests the significance of Fonseca, it also explores the uneasy relationship of Goa with its artists, or church as a coloniser's tool, or India's definition of modernism.

While the church was reluctant about embracing Fonseca's art, the people of Goa helped him sparingly through the course of his life.

The custodian of Fonseca's art remains the Xavier Centre of Historical Research (XCHR) in Goa. Besides having purchased some early copies of his works, it acquired his entire unsold collection.

The story of the artist not going further than a small circle is also the story of philanthropy for the arts in India. Many brilliant artists have been lost to obscurity because India is still figuring out its philanthropy to lift that brilliance to the fore.

Other important Fonseca collections are at the Jesuit Mission Office in Germany, the archives of Fr. Übelmesser SJ and Fr. Klaus Väthröder SJ, both German Jesuits from Nürenberg, Germany.

JJ School of Art Vs Santiniketan

Chapter two leads the reader into the academic world of the art schools of pre-Independence India. Fonseca finally went to Santiniketan College (founded near Calcutta in 1901) from 1929-31, his decision to learn here was deliberate and calculated.

He came from a well to do family in Goa. Like many landed gentry of early modern India, he was deputed to take on a career that was prestigious.

He tried and thus he began his study in Medical School. He gave that up fairly early and went to join JJ School of Art in Mumbai.

Despite the wealth and cultural inclination of goans, Fonseca wanted to pursue art through a traditional route. He wanted to root himself to India to create an authentically valid language.

This is why he left JJ School of Art for its western focus on British Realism and shifted to study in Calcutta, the land of civil disobedience, the land of Indian cultural revivalism and nationalism.

Fonseca met Abanindranath Tagore at an exhibition of the Indian Society of Oriental Art in Calcutta. Abanindranath decided to teach Fonseca, and this was the first remarkable shift in the artist's life, craft and lifestyle. He truly took on the Guru-Shishya parampara (Mentor-Disciple Tradition) to learn, create and remain inspired.

Chistian iconographic idioms became Fonseca's language of cultural patriotism and in many significant ways he was the bridge between the religion and the other. His art was opening a dialogue with the conservative Christian faith about inclusivity of minority cultures.

His art was a bridge between social divides. The reader is taken through the artist's unsuccessful attempts at impacting religion and at some places being held in contempt of the very religion that he was deeply devoted towards.

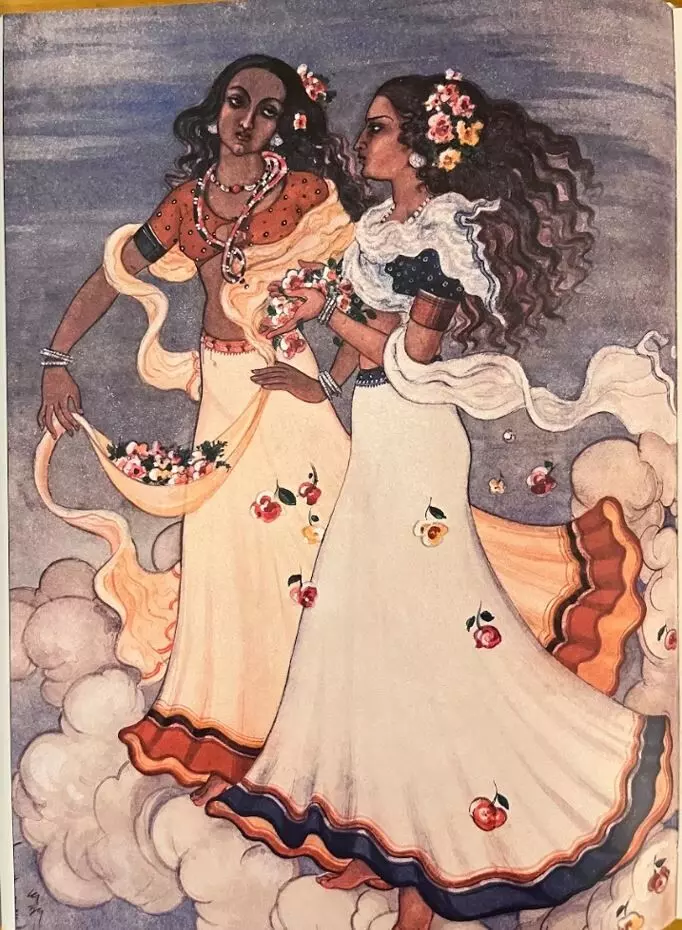

As Fonseca was building out his style Nandalal Bose (1882-1966), a pioneer of Modern Indian art and a key figure to contextual modernism had the most profound influence on Fonseca, as his teacher. It was under his training Fonseca adopted the Neo-Bengal Style with a nationalistic fervour and purpose.

Man on a Mission

Fonseca finally developed a mission: "the presentation of a vision that could impart to Christians and Christianity in India a visible national character of Indianness and thereby connect them to mainstream civil society. A project to modernise Catholic self-understanding, to enhance attitudes of social inclusivism, responsibility and participation in nation-building."

Fonseca was painting at a time when the Portuguese controlled Goa, which was largely Catholic. Fonseca's rendition of themes from the Bible were deliberately indianised. He painted Mother Mary in a saree, and Jesus in Indian clothes, all of which was severely opposed by the Portuguese churches of Goa.

Despite criticism as one will see in this book, this is an artist whose artworks command your attention, despite his oeuvre missing from most school and college books.

Modernism in India

Chapter three is the story of India through its modernist revolution championed by its artists, architects and writers. Fonseca was questioned for his role as a modernist as he was painting conservative themes using traditional inspired techniques.

Living in Goa where the West and East merged, and the irony of adapting the West to the East did not work in his favour too.

How did modernism work for India that had been colonised and then was searching for its own new and relevant identity? Something that represents its antiquarian wealth and its ability to rise to the times. In a strange way Fonseca was grappling with this in his own career. The parallels are strewn all over this book.

India's modernism never took on any monotone. India was plural before the Colonists came, and India's plurality was so deep that it permeated any foreign influence leaving a mark. When the Portuguese brought in western elements too foreign to allow religion to become vernacular. Fonseca brought in the solution.

However, a conservative approach by the Church did not allow for such new interventions. Yet, the interventions were deemed traditionalist in its iconography and Fonseca declared too rooted in conservative Indian representation. The irony was riddling.

This chapter revisits the question about what modernism is and when it started in India. India modernism has many facets and while that was difficult to understand according to western concepts, Indian artists and authors did a good job just carrying on with their own multidimensional modernity.

Fonseca in his career took on a responsibility to modernise 'Western Christianity' to become better suited to India. He led it through his nationalism in languages that stoked Indian cultural nostalgia but urged the world to conform to Indian standards where in India, to suit Indian palettes. We learn here how Fonseca took on the Church. And he failed. He even got called a heretic.

The Tragedy of Every Artist

This classic journey of the artist with the country and then more so with his home city most often failing tragically to be accepted for their ways were too late is what we learn here too. Goa despite being an international entrepôt never engaged with indigenous forms.

It focused on how Western standards got adopted in foreign soil, and that was a big blow to the native language of modernism in Goa. Despite the art being lost for as long as it remained unpurchased, there is important history in his body as one will understand it in present times. Cultures and spiritualities can be reconciled and harmonised. He was a bridge between the two extremes, for a country like India.

Indian Craftsmen and their Might

The fourth chapter goes into an interesting realm, the role of Westernisation and Christianity in Goa, and the role of natives towards furthering Western Christianity. Hindu carvers and painters were proficient in building the Christian material culture of Goa, be it ivory sculptures or the big churches and murals, until they were banned in 1565.

Goa was the first Westernised city of the East. It became representative of modernism in art, literature, music, and education. Public infrastructure, besides the religious, began to take on a secular nature too. Libraries and charitable centres began. So rich were the religious and secular cultures, that the sculptures have now been all smuggled or stolen.

It was through the artist's tryst we realised that his art was an ode to his religion no matter who rejected it. His religion was also his lifestyle, as becomes evident in this chapter when he lives in an Anglican Ashram in Pune for seventeen years.

It was here he produced a huge number of Christian paintings in typically Indian style. The Our Lady of India, The Seven Dolours of Our Lady, The Flight in Egypt, The Nativity, and were hailed by art critics as outstanding masterpieces.

Church Turns a New Leaf

In Chapter five we learn how Christianity after decades of revolting against localisation, was beginning to turn a new leaf. Thus began a new programme which focused more on presenting a tenacious endorsement of cultural diversity, to be embarrassed under all encompassing universalism.

Mounting criticism against the imperialist nature of the Church led it to become the first international patrons of indigenous art. Many books began to be published and missionary museums came to be built. This is when Fonseca's art travelled abroad for the purpose he has intended this art to come about.

As one reads through the book, one realises the trials of a man on a mission. While the artist was focused on one tangible result from his work, his art got slotted into an inconvenient category for a while. Only for a while though, because after the church recognised and displayed his works around the world, this category became his badge of honour.

The artist's story brings forth many connected stories. As one examines his life from all the angles of young India and its growing pains, one can say that India is still young and has a long way to go. But, along the way it produced brilliant patriots and intellectuals who continue to add dimensions to the country's plurality, syncretism, diversity and intellectual capital.

Fonseca is a historic Modern Master from South Asia and his art is about transcultural artistic heritage enunciated repeatedly and beautifully by the author.