Ghoom Nei Challenges The Audience

The original play was based on the political unrest, Workers’ Union strikes of the 1970s

A performance in the form of a play is commonly understood to be a medium of entertainment. In some cases, it is an agency to trigger the conscience of the audience to respond to the incidents the play brings to ‘reality’. The audience may not be aware of these incidents, and if aware, are not shaken enough to respond or take action.

Ghoom Nei is a play authored by Utpal Dutt, who was responsible for reaching the works of Shakespeare to remote Indian villages through theatrical performances in Bengali. Theatre formed the core of his commitment, much more than his successful career in Bollywood films as a comedian and a villain.

Ghoom Nei was performed to a full audience recently at a packed theatre in Kolkata by the noted but low-key theatre group Icchemoto founded and directed by Saurabh Palodhi. The original play was based on the political unrest and the Workers’ Union strikes of the 1970s.

Palodhi shifts his adaptation to place it on the Berhampore-Kolkata Highway on the same time-scape, but shifts the focus from the general, the struggle of the masses pressurised under the dictatorship of the ruling class, to the specific, the everyday struggle of a group of truck drivers who drive only at night, and if and when they fall asleep on the steering wheel, we know what is likely to happen.

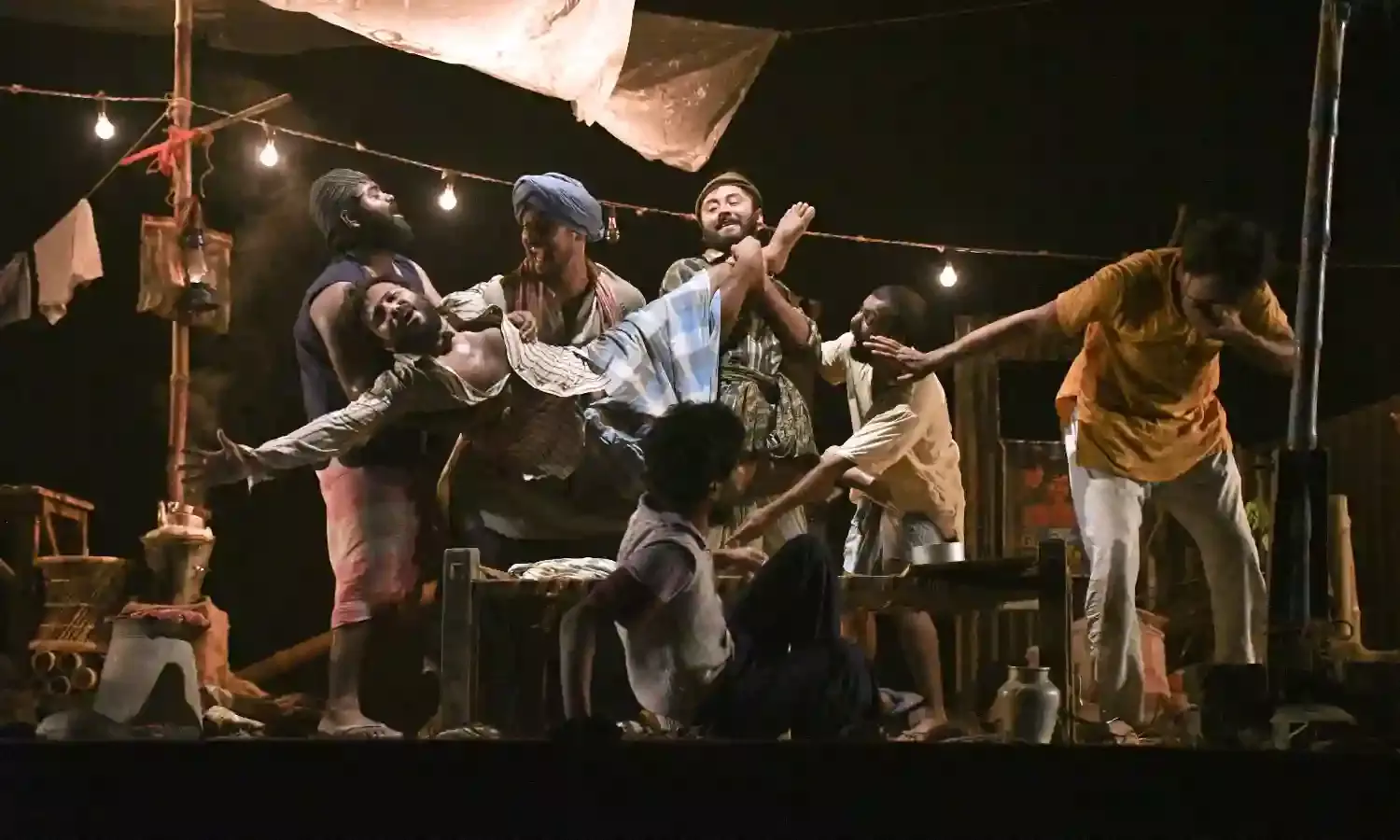

Just before the curtains go up, the audience is informed that this play is not for the genteel and educated elite, and those who belong to this class might find it disturbing. Before we try to understand what this means, the curtain goes up on a ramshackle dhaba placed on one side of the highway. The truck drivers walk in and out of the shop asking for a cuppa, or a peg from the country liquor bottle the tea shop owner dishes out only after midnight.

Some of them also ask for a dinner plate of mutton curry and rice or chapati, and one learns how close the dhaba-owner is with these truck drivers. It is a ramshackle one but is a place not just for a tea-break, but also an informal meeting place for these struggling truck drivers and the dhaba owner.

Though the play is focussed on the truck drivers and the dhaba owner, there are a few from the ‘genteel class’ such as a journalist and his assistant who really cut a sorry figure with their pretentiousness which places the truck drivers in brighter focus in comparison.

An old madman who talks nonsense begins to make some sort of sense towards the climax. He decides never to take tea for free from the dhaba owner, who is a kindred soul equally burdened by the struggles of life just as the truck drivers are. A skinny young man who stepped into the world of work in this remote place is suicidal for want of employment but the others try to prevent him from committing suicide.

There are as many as 17 characters in the play, including truck drivers, a dhaba owner, a madman, an unemployed man, an elderly gent, and two reporters looking for a story, among others. All of whom play out the plight of people on whom the economy is said to rest, but who generally go unnoticed.

They converse in a language the audience is not quite familiar with. It is filled with invectives, and double entendres with no concessions made with what is known as ‘genteel conversation’. They have come together because the gate they need to cross to get onto the highway is closed, and the corrupt cop is busy collecting his hafta from the drivers mostly with fake complaints. The truckers have gathered together because the bridge they need to cross is being repaired.

This gels with the characters and the situation well. There is a wonderful sense of timing and cued responses by every actor. You can feel their pain and struggle to bring some semblance of meaning to their lives. They, starved of sex in their marriage, seek pleasure out of other relationships that keep the legitimacy of their kids in doubt.

But they also have fun and joke among themselves, their vocabulary flooded with double entendre and vulgarity even to laugh at themselves. The truck drivers are united by their occupation that does not offer the scope for a night of sleep. Their lives are reduced to sleepless nights, living away from their families literally and even philosophically. Their life is full of weariness, and financial stress of being exploited by the truck owners who fines them and deducts their meagre salaries on the slightest of excuses.

It does not matter if the truck drivers are Muslim, Hindu, Sikh or whatever else. They are united in their unwashed clothes and countenance and of course, their language, as dirty as can be.

I could see a couple, probably a father and his young daughter, walk out of the theatre in the middle of the play, but the rest of the audience sat right through. The characters’ body language is as unkempt, crude and vulgar as one can imagine, and all this makes the play almost walk off the stage, step into the audience and shake each one to step out of their fanciful world.

As the play slowly, steadily and firmly moves towards the closure, it makes a powerful Communist statement. Two characters spread out a hand each, holding an axe and a hammer to spell out the recognised political symbol of the Communist Party of India. The audience breaks into loud applause.

The madman’s soliloquy is a bit melodramatic and could have been left out. The sets, the lighting, as dim as it ought to be in this single set play, are structured with great authenticity. The beautiful songs sung on stage by the actors themselves draw from a rich repertoire of different styles of folk and other music that rounds off one of the most outstanding performances I have witnessed in a long, long time.

Dutt wrote the play decades ago but its resonances are loud and clear today within the top-heavy political climate we live in. What an astounding performance and a brave one as well. Ghoom Nei is a play that challenges its audience to shake off their comfortable space, and see what life is really like among struggling and poor people whose struggles are such that it never allows them to sleep. That is why it is called Ghoom Nei meaning “no sleep.”