Have You Heard About Batanagar?

Little is known about Bata’s first few years of production in Konnagar

Ninety years ago, Czech footwear company Bata Corporation started manufacturing in India. The factory was set up in Konnagar, a town that is around 20 kilometres from Kolkata. Later, the company moved to South 24 Parganas, West Bengal, and set up Batanagar, one of the most ambitious industrial towns of its time.

Although the history of Batanagar is well-documented, little is known about the company’s first few years of production in Konnagar. A local group of heritage activists from Konnagar, Konnagar Aitijhya Parishad, has attempted to uncover its history in parts.

Arunava Sanyal, a resident of Konnagar and a member of the group, now employed with Amul, has a keen interest in industrial heritage and mediaeval temples.

“When I first started digging the history of Bata in Konnagar, I realised that we might not have an interest in it here, but former employees of Bata are keen to talk about it,” said Sanyal over a phone call from Agartala, Tripura, where he now works.

According to Sanyal, he looked for blogs of former Bata employees and emailed them with the hope of finding some photos or texts about the factory in Konnagar. Among those who replied was Jan Beranek, son of a former Bata employee. He put Sanyal in touch with Olek J Plesek, the son of Oldrich Plesek, another former Bata employee who worked in India.

Plesek connected Sanyal to Helen Giglietti, the daughter of Frantisek Staroba. Staroba was among a group of 19 Czech workers who came to Konnagar to oversee the beginning of production in India, according to Jan Baros, the publisher of Batanagar News and documentarian of Bata in India.

On Sanyal’s request, Giglietti went through her parents' photo archives and found a section titled, ‘Fotografie s Konagaru’, containing photographs of Frantisek Staroba and Olga Staroba (nee Seifertova) in Konnagar.

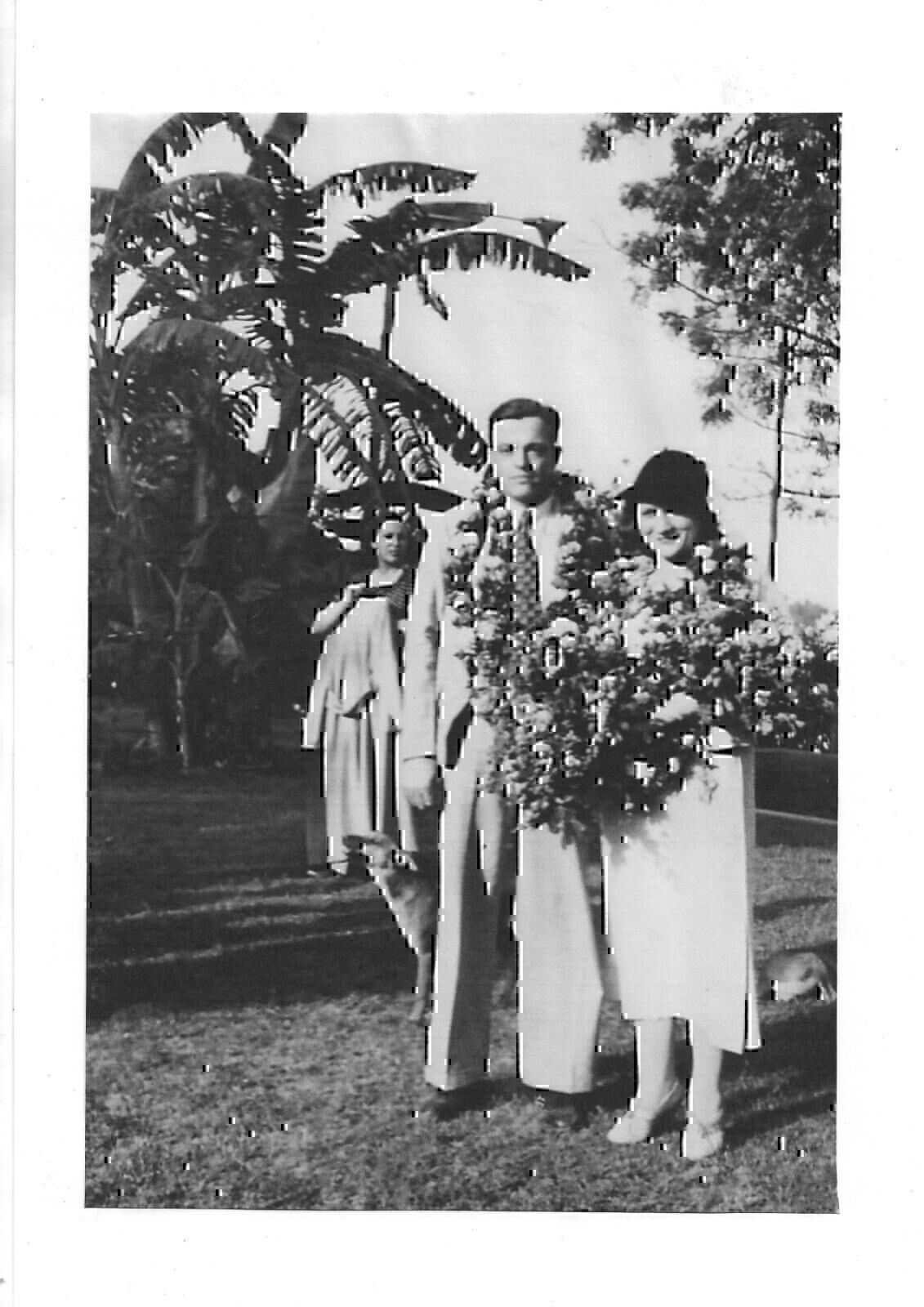

Plesek told Sanyal that the Starobas got married in Konnagar on May 14, 1933, two weeks after the first batch of rubber plimsoll shoes were produced there. He also claimed that their marriage was the ‘first Czech union in India’, and found a place in Bata’s recorded history.

Frantisek Staroba and Olga Staroba got married at the Serampore Church (Photo Credit: Olek J. Plesek)

For Sanyal, the photographs were a breakthrough. He pointed at an abandoned factory complex in Konnagar by the Hooghly river, identifying it as the site of Bata’s first factory in the country.

“Uncovering the history was like solving a jigsaw puzzle,” he says. “I was looking for photos of the Bata factory from 1932-1931 and the first photo I got was from Jan Baros’ book The First Decade of Batanagar.

“After that, I contacted Milan Balaban, a researcher at the Bata Information Centre, who sent me a photo of the factory published in the ‘Ziln Newspaper’ from March 29, 1933. I saw several similarities in it with the present-day structures.”

Photo of Konnagar Bata factory in Jan Baros’ book (Photo Credit: Jan Baros)

A group photo of the Czech workers in Konnagar (Photo Credits: Helen Giglietti)

According to a paper co-authored by Balaban with Jan Herman and Dalibor Savic, by 1927, Bata had established retail shops in India, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Singapore. Bata’s biggest competitor in the South Asian market then was shoes manufactured in Japan.

Japan was closer to India, meaning lower transport cost compared to shoes from Zlin, and as a result, in the early 1930s, “millions of pairs” of Japanese shoes were being imported to India. Compared to that, Bata shoes came in only “tens of thousands”.

To make matters worse, the British pound fell by almost 40% after the Great Depression of 1929 and preferential quotas and protectionist tariffs were introduced by the colonial administration in response. It made the export of Bata shoes to India unprofitable.

In the wake of stiff competition, through 1930-31, Thomas Bata Sr undertook what The New York Times then described as “one of the most lengthy and ambitious sales trips yet made by the aeroplane”, and among other cities around the world, he also came to Kolkata in December 1931.

The company had earlier sent a group of 14 workers to the city to establish shops and train local workers, but sales were still not picking up.

In January of 1932, Thomas Bata Sr finalised the renting of a factory in Konnagar, with plans to first establish a godown and then start production. According to Baros’ book, Bata rented the ‘old Hatirkool Factory in Konnagar’ from one Anderson Wright for five years. It had been an oil mill before that stopped operations in the Great Depression.

Inside the abandoned factory complex in Konnagar (Photo Credits: Shamik Banerjee)

Baros writes: “The factory had not been working for a very long time and its empty structures were in a state of decay. Within one single night the whole office and the godowns from Calcutta were shifted there, together with the fourteen Czechoslovak boys who for the first time in India found a steady home.”

Thomas Bata Sr passed away on July 12, 1932, and his brother Jan Antonin Bata took over the business. Although there was pessimism that the company’s expansion plans would be thwarted following the founder’s death, quite the opposite happened. Jan Antonin Bata not only oversaw production in Konnagar but also, in 1934, laid the foundation of Batanagar.

Another group of 19 workers, among whom were the Starobas, came from Ziln in the Bata-owned SS Morava ship, specifically to start production in India.

Olga Staroba working at the Bata factory in Konnagar. (Photo Credit: Helen Giglietti)

They brought “134 machines, 98 electric motors, 5,000 pairs of shoe lasts, 108 cutting knives and 300 tons of materials”, and arrived in the port of Calcutta on February 23, 1933. The ship took seventeen Indian youths back to Zlin for a special three-year training, so they could come back and work for the company in India.

Baros documents that the assembly line in Konnagar produced the first batch of 1000 pairs of plimsole shoes on May 1, 1933, and notes that the event was celebrated with great enthusiasm by Bata workers in Ziln.

According to Sanyal, after Bata left the factory premises, an Indian businessman named Fulchand Bhagat bought it and again turned it into an oil mill. The oil mill shut in the 70s and the factory has since been mired in a family dispute. It lies in a ruinous state today, covered in bushes, and protected by a septuagenarian security guard.

“To be honest, the complex will stay as it is, except, perhaps, the bushes will spread even more,” Subhadeep Kansabanik, the secretary of Konnagar Aithijhya Parishad said.

Kansabanik is a manufacturer, but most of his time goes into unearthing the history of local temples and colonial era houses in Konnagar. He has worked with the Konnagar Municipality to preserve a bungalow belonging to Abanindranath Tagore, eminent artist and nephew of Rabindranath Tagore.

Recalling his experience of preserving the bungalow, he highlighted that the personal initiative of Bappaditya Chatterjee, the previous chairman of the Konnagar Municipality, was instrumental. He says that the key to preservation of heritage in such a hyperlocal context is the personal drive of people in power.

“For the Bata factory, only people in power or big institutions can do something to preserve it, people like us cannot. If the municipality could buy the land, they could have made plans. Now, you can only hope that after five years something can happen, like a museum or something, but nothing beyond that,” he said.

“As it had been abandoned for years, the compound is filled with bushes. It will take a project with a huge budget to restore and preserve it as heritage,” he added.

He is critical of the Heritage Commission of West Bengal, complaining that it exists just as a formality. “They are always more eager to cater to the demands of the real estate developers,” he alleged.

“In most cases, the commission is fine with just preserving the structure and letting the rest be taken up by developers, and then there is maintenance and other costs also. So, it’s hard to imagine them preserving the Bata factory,” he added.

Sandipan Chatterjee, a Kolkata-based architect, echoes similar concerns. “There are real estate people in the state Heritage Commission and its president is also inclined towards them,” he said, adding, “Instead of preservation, what really happens is the active degradation and demolition of heritage buildings so that new construction can be done on the land.”

A resident of Konnagar, Chatterjee is currently pursuing a PhD from the School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi. As a member of the ICOMOS, India chapter, he was part of a group that unsuccessfully advocated for the preservation of the Patna Collectorate building, which was demolished in January 2023.

“In Konnagar, we lack pure open spaces for the public. If the factory is renovated and preserved by the state, it can be a source of revenue for them.It is by the river and has a wide vista. With the National Waterways I being announced, cruise tourism will boom soon, and renovating the building can pay off further for the state.

“The Bata factory is a beautiful, scalable project and if renovated, it can be a wonderful place. The public can play a very important role in this.

“Yet, due to the little importance attached to industrial heritage at the state and the national level, Konnagar Bata factory would lie derelict, and eventually will be demolished to pave the way for new constructions on the land.

“In India, there is little interest in industrial heritage, but in European countries there is a lot of importance attached to it. If they had known Bata’s first factory was established here, they would have been more aware, or even tried to preserve it,” Sanyal said.

Kansabanik, on the other hand, prefers to be hopeful, in spite of the odds. “I believe things around us are ‘negative’ and we have to turn it into ‘positive’ through work. I saw Abanindranath Tagore’s bungalow turn from a derelict site into a retrofitted building, so you never know,” he said.