Homeless In The City

Delhi, Maharashtra and West Bengal have the highest homelessness

Nasreena was checking a list of spellings in a notebook. Beside her stood an eight-year-old resident of the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB)-run Nizamuddin Shelter Home, peering in and tracking her tick marks. Around them were 12 other children, aged between 6 and 12 years, engrossed in school work.

Nasreena is a teacher appointed by the Society for Promotion of Youth and Masses (SPYM) to help children in the shelter home with their studies. She showed us a register with 98 names. The children, mostly residents of the shelter home, call her “tuition teacher”. “I help them with the basics, so they can cope with school better,” said Nasreena.

In the same room are rows of beds, some empty and others occupied by napping men and women, mothers cradling their babies, grandmothers entertaining grandchildren, and young adults fanning themselves and engrossed on their mobile phones. Beneath and around the beds are the residents’ belongings.

Inside the Nizamuddin family shelter home. The beds are grouped in twos or threes, depending on the size of the families.

The beds are grouped in twos or threes, depending on the size of the families, and these belongings – buckets, suitcases, fans, pillows, plastic and tin boxes, utensils – demarcate these groupings. Meant to provide a temporary roof over the heads of the homeless population in Delhi, the personal belongings and routines are markers of permanence.

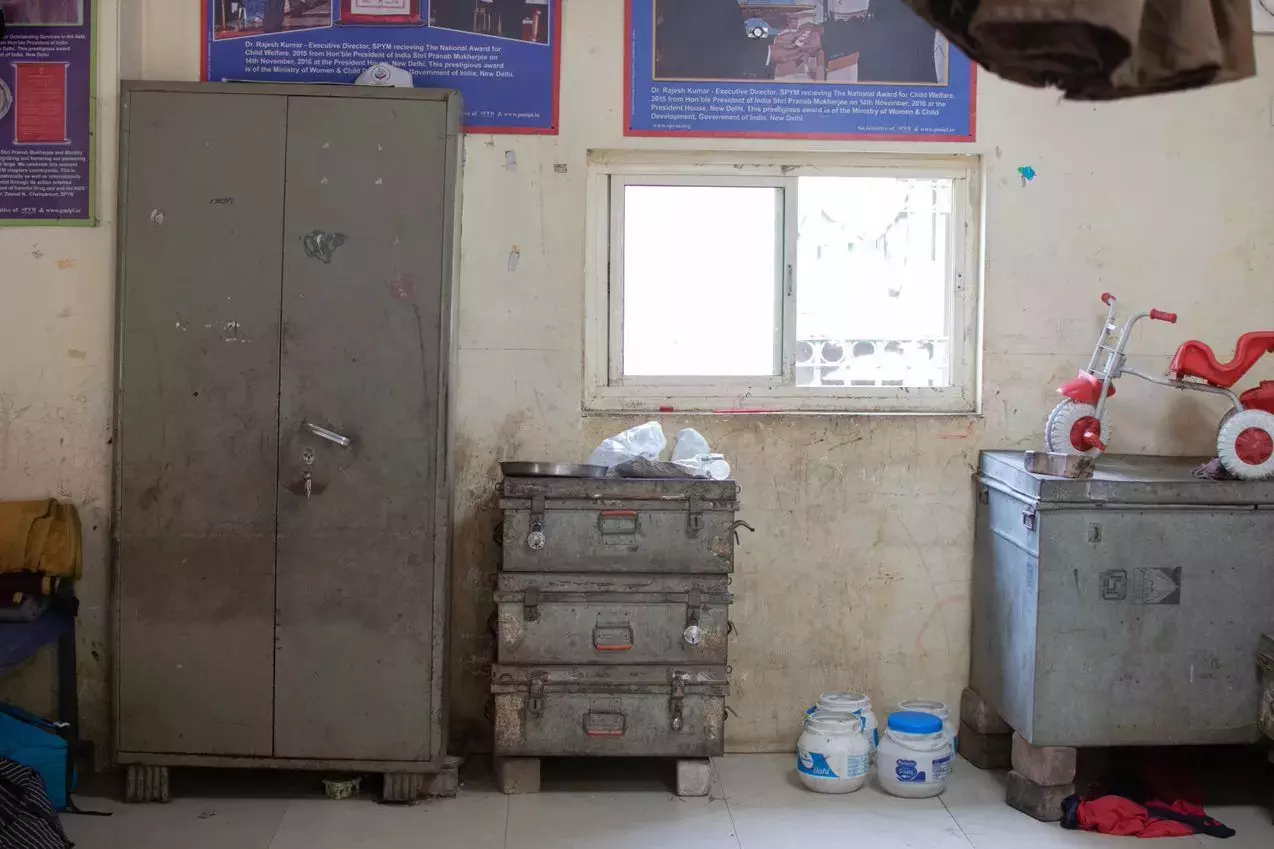

Personal belongings of Nizamuddin rain basera residents.

Forty-five-year-old Sunita, matriarch of a family of three generations living at the “rain basera” (shelter home), had celebrated the birthday of her grandchild, Aanchal, at the home the day before. “She was born on Teacher’s Day!” she told us enthusiastically. Aanchal was born in the shelter home.

Sunita has six children, of whom three live in the shelter home with their families. She works as a cleaner in the home, beginning the day’s work by sweeping the premises at 7 A.M. “There are six washrooms. I clean three of them and another cleaner does the remaining,” she said.

Her family has been staying at the home since it opened around two years ago. Before that, they were in the shelter home “under the Nizamuddin flyover”.

Sunita with one of her sons and grandson at the Nizamuddin shelter home.

A few beds away, lives the family of Sunita’s second son, Mustafa. “Just before the day of my wedding, we were evacuated from our slum,” he said, alluding to the 2016 evacuation drive in Kathputli Colony in Shadipur. They were relocated to a transit camp in the Anand Parbat industrial area.

“We couldn’t bear the heat under the tin roof there,” said Mustafa. Rupa, his wife, prefers living in a jhuggi, a house of her own, like she used to before getting married. “Jhuggi ke liye jagah hota toh rain basere mein kyun rehte?” (If we had some land for a jhuggi, why would we live in the shelter home?) “My mother-in-law, despite trying to set up a jhuggi for so many years, hasn't succeeded,” said Rupa.

Mustafa and Rupa at the Nizamuddin shelter home.

She works as a rag-picker and Mustafa is a manual labourer. They earn about Rs. 400 on good days, if they manage to find some work. Their three-year-old son goes to an ‘anganwadi’, the government day care center. “We cook our own meals in the shelter home because the earliest food arrives is 11 A.M., by when we have already left for our daily work,” said Rupa, who had made aloo paratha for lunch the day we met.

At the Nizamuddin shelter home, some families prepare their own food while others consume what is provided at the centre.

Each bed has blue or brown curtains, mostly rolled up over the bedposts for ventilation. “If families need privacy, we pull down these curtains,” said Rupa, pointing above to the blue fabric. She delivered both her children in the shelter home.

Her first baby was stillborn. “My mother-in-law has the skill and knowledge of a midwife. She helped with the second delivery and cut the umbilical cord,” she recalled. During the delivery, the same blue curtains were pulled down.

The 2011 Census of India defines houseless households as “households who do not live in buildings or census houses but live in the open on roadside, pavements, in fume pipes, under flyovers and staircases, or in the open in places of worship, mandaps, railway platforms, etc.”

According to the report, India has 9,38,384 urban houseless population, of which 24,966 are in Delhi. Maharashtra and West Bengal are the States with the highest homelessness. Many civil society organisations like the Indo Global Social Service Society (IGSSS) and Ashray Adikar Abhiyan (AAA) have claimed this is an undercount, based on their own headcount in 2008 and 2000 respectively. According to the IGSSS report, Delhi comprised 88,416 homeless people in 2012.

Fatima, caretaker at the women’s night shelter in Kalkaji, said, “Most women who stay here are migrants from neighbouring States. Women who have faced harassment and domestic abuse also come here to escape their circumstances. Pilgrims to the Kalkaji temple, too, temporarily stay here for a few nights at a time.”

The women’s rain basera at Kalkaji Mandir.

At this night shelter, a large hall, were 21 single beds, two air coolers, four fans and one TV. A CCTV camera was facing the entrance of the hall. Pooja, another caretaker, said all beds are mostly occupied in the night and there have been times women are turned away for lack of room.

A CCTV camera faces the entrance of the Kalkaji shelter home.

Here too, like at the Nizamuddin shelter home, some are permanent residents. They are women who sell flowers and prasad (devotional offering) to devotees on the streets leading up to the Kalkaji temple, a popular tourist spot in the city, in the day and retire in the shelter home at night.

Women living at the Kalkaji rain basera sell flowers and prasad to devotees on the streets leading up to the Kalkaji temple during the day and retire in the shelter home at night.

Aadhaar card is mandatory if one wants to be allocated a bed in these shelters, both Fatima and Nasreena confirm. “We organise Aadhaar card drives regularly. Birth certificate or any form of ID like electricity bill is sufficient for getting an Aadhaar card,” said Nasreena. “They have to prove they are residents of Delhi. That’s the only requirement.” But, what if one does not have any form of identity documents? “We inform the police of such cases,” she said.

This insistence on ID proof has left the shelter homes out of reach for many homeless migrants, like Muskan, who lives in a makeshift tarpaulin tent on a pavement in South Delhi opposite the Sai Baba temple on Lodhi International road. In a tent supported by a building’s boundary wall on one side and held to the ground by bricks and concrete blocks, she lives with her husband and two children.

The tent barely allows for two people. The children have not been enrolled in a school. Having migrated to Delhi as child-bride from Uttar Pradesh, Muskan leads a particularly vulnerable and precarious life on the streets, owing to her gender and class.

Muskan lives in a makeshift tarpaulin tent on a pavement in South Delhi opposite the Sai Baba temple on Lodhi International road.

A victim of domestic violence by an alcoholic daily-wage earner husband, she narrated an incident from recent memory: “A man entered my tent one night and lay down beside me. I panicked and got up, but no one was around to help. He left soon after and thankfully nothing happened to me.

“Shelter homes ask for Aadhaar card details. My husband and I both do not have any identity documents. To get us an Aadhaar card, they ask us for electricity bill or voter ID. We have none of these. Even to find work as a house-help or sweeper I have been asked to show my Aadhaar card.”

Housing and Land Rights Network (HLRN) in a 2014 report Violence and Violations: The Reality Of Homeless Women In India notes that, “Homeless women suffer the worst kinds of violence and insecurity and are vulnerable to sexual exploitation and trafficking.”

The sex ratio of the houseless population of India is just 694 females per 1,000 males. Literacy rate amongst this group is 56.07% compared to the national average of 74.04%.

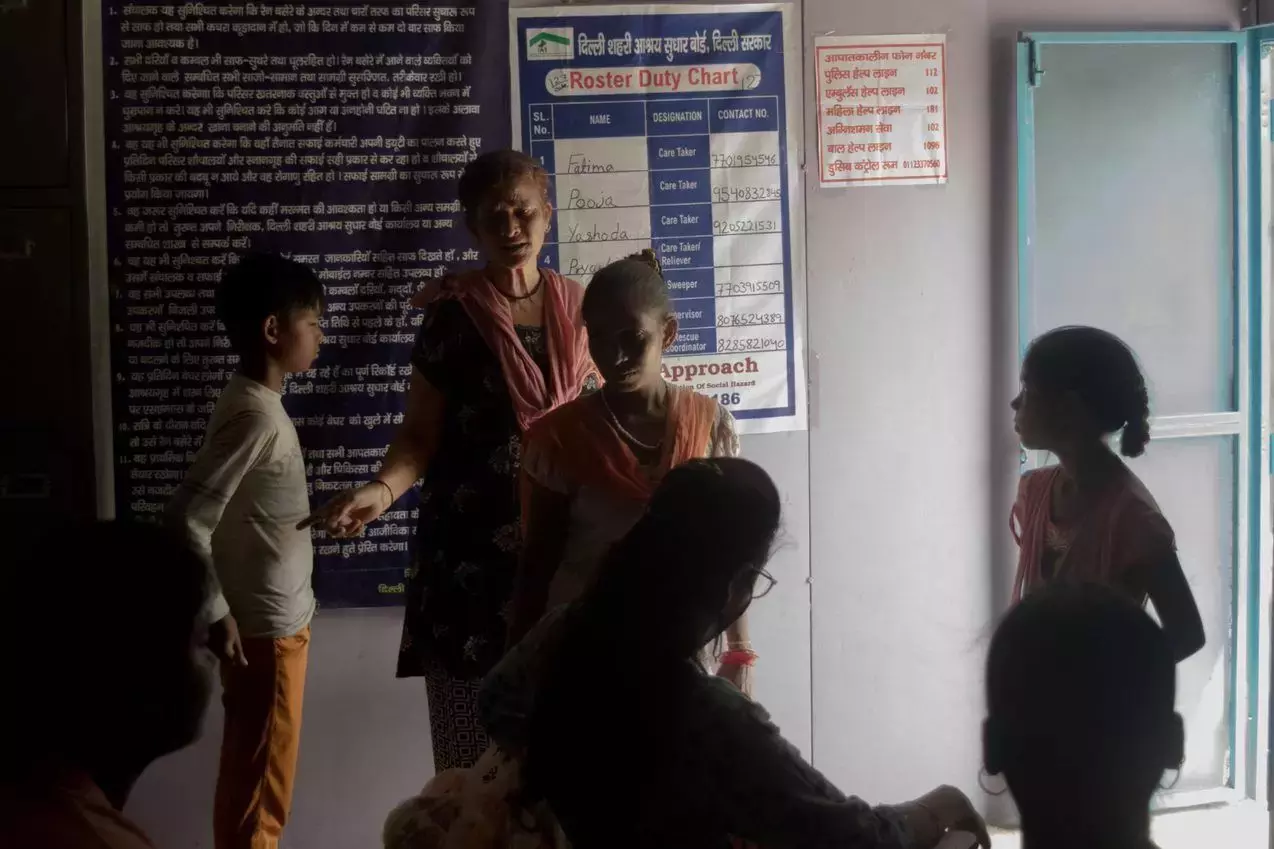

Back at the Kalkaji night shelter, Priyanka Sharma, Project Investigator from an NGO Sudhi Foundation, was counselling a mother and son duo. “You must send him to school daily. You must also tell him not to run away and skip classes. He is your son, he will listen to you,” she was telling the mother, while the 11-year-old son looked on.

Priyanka Sharma, Project Investigator from Sudhi Foundation counselling a mother and his son about attending school regularly at Kalkaji shelter home.

“We help them obtain identity documents and enrol the children in government schools, but we are unable to stop dropouts later,” she explained. “He says he does not understand what is being taught in class. That’s why he is disinterested in attending school,” the mother explains.

It is this gap that “tuition teachers” like Nasreena in the Nizamuddin shelter home are trying to bridge. But the intervention is ad hoc and insufficient.

A child finishing her school work at the Nizamuddin shelter home.

Class five student Kanhaiya, at the Nizamuddin rain basera, is the only one out of five siblings to attend this “tuition”. His 35-year-old mother, Kalpana, is originally from Damoh in Madhya Pradesh but has been living in Delhi for the past 22 years. She works as a construction labourer, earning Rs. 400 on days she can find work. Her husband is a rag-picker.

“He doesn’t work now,” Kanhaiya interjects, “because a dog bit him recently. They gave him many injections for it.” Kanhaiya said he is scared of injections and hid his face behind his mother. Kalpana, who was married at 16 years of age, said she needs Rs. 10,000 per month to sustain the family, but hardly ever earns enough to make ends meet.

Kalpana, a construction labourer and resident of the Nizamuddin shelter home, says she needs Rs. 10,000 per month to sustain her family of 6. She hardly ever makes ends meet.

Kalpana’s family, unlike Rupa’s, eats food provided by the shelter home. Kanhaiya made a face and said, “dal and sabzi tastes like water. But, I like the rice, it is okay.” There is a TV on the wall opposite their beds. “Kharab pada hai ye,” (It does not work) said Kanhaiya, looking in its direction. “I have been asking everyone to pay ten-ten rupees to get it repaired. But no one wants to pay,” he complained.

Kalpana said they often lose their personal belongings to theft, “It is an insider’s job. Someone from amongst the shelter home residents is the thief, because no one from outside can come in.”

Most homeless migrants in Delhi are from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Rajasthan, explains Aravind Unni, Urban Poverty Thematic Lead, IGSSS. “Lack of access to livelihood is a major cause for this migration,” he said.

There is some distress migration, too, owing to natural calamities like droughts, in the Bundelkhandi area for example. A substantial number of women are deserted and rendered homeless due to familial trauma.

It was 28-year-old Rekha Mehta’s second day at the Kalkaji night shelter. Unable to bear the physical abuse by her alcoholic husband, she had left her house in Udham Singh Nagar in Uttarakhand and come to her sister’s house in Delhi with her 5-year-old daughter. “My sister’s house is small. She lives with her husband and two children. I couldn’t stay with them for too long,” Rekha said.

Unable to bear the physical abuse by her alcoholic husband, 28-year-old Rekha Mehta had left her house in Uttarakhand and come to her sister’s in Delhi with her 5-year-old daughter.

She is handicapped in her leg, owing to a fire accident in her childhood, and has left behind her 13-year-old son with her parents. “Bhagyawati (her daughter) wouldn’t stop crying, that’s why I brought her with me.” She had Rs. 400 with her, money her sister gave her before she left for the shelter home. “I will stay here only, I will not go back. I can do all kinds of work. I just have to find some work now. I must get my daughter educated,” she said, tearing up.

Sharda, 40, has been staying at the night shelter for over a decade. She has now been employed by the shelter home as a cleaner, earning Rs. 7,000 per month. After completing her duties in the shelter home, she steps out onto the street to help her husband and sons sell flowers and prasad.

Sharda helps her husband and sons sell flowers and prasad on the road leaing to the Kalkaji Mandir, a popular tourist spot.

Since the shelter home is a women’s-only shelter, the rest of her family lives in a tent on the street. “I came to Delhi with my sister at the age of 18 from Rewari, Haryana,” she said. Her six children, five boys and one girl, were all born in Delhi, as were her grandchildren. Wouldn’t it be nice to live with her husband and children? “Of course. But the children are all grown up now. I cannot comfortably live with them in a small house.”

Sharda, 40, has been staying at the Kalkaji night shelter for over a decade.

Two of her sons are still in school while Akshay, her third son, is a student of Deshbandhu College, Delhi University. “I have discontinued because I couldn’t pay the fees after the pandemic,” Akshay said, “Waise bhi padhai karke kya karna hai? Yahi toh karna hai? (What is the use of education? I have to sell prasad anyway.)”

Sharda’s third son, Akshay.

Her tattooed arms draw our attention and we ask what the initials stand for and who the names are. “‘Shivam’ was my 19-year-old son who died in an accident when he went on the Kawad Yatra in 2016.” She explained that the ‘S.S.M’ tattoo stood for “Sharda, Santosh, Manisha.” Who is Manisha? “Pyaar se mujhe Manisha bulate hai” (I’m called Manisha fondly).

Sharda has multiple tattoos that read ‘Shivam’ on her hand. Shivam is the son she lost to an accident.

What if one day she is asked to leave the shelter home? “Why will anyone ask me to leave? I will stay there for as long as it exists,” she is defiant.

Most of the homeless population in Delhi are second-generation migrants. If a person was born in a city, can we still call them a migrant in that city? In other words, is homelessness a product of inter-State migration?

“Homelessness is not a migration issue, it is an issue of intent, of whether the state wants to put in resources and invest in issues surrounding homelessness,” said Aravind, adding that homelessness is intergenerational and societal. How the Census defines homelessness can only capture data but not provide solutions to it.

Policies and interventions cannot be framed with this reductive understanding of homelessness. According to Aravind, “It misses that homelessness can be fluid. Although accounting for a small portion of the migrant population, there is value in an expansive definition.

“Seasonal migrants, for example, are homeless in the cities they migrate to for work, but have houses back in their villages; people migrating for healthcare and women fleeing from abusive homes are other examples.”

The state has, for long, viewed homelessness as a problem that can be solved by constructing more shelter homes. “Shelter homes are a stopgap solution that has proven insufficient,” said Aravind. Delhi, boasting an impressive number of shelter homes, is an example of this. Unless the issues that are contributing to homelessness in the first place are addressed, any homelessness-reduction program is futile.

The DUSIB-run Nizamuddin shelter home complex.

“The homelessness discourse must be connected to the wider housing discourse. Can the shelter homes be linked with rental housing? How is the state reaching out to the homeless population? What are the services it is offering them?” he asked.

The narrative that puts the onus of homelessness on the homeless demographic by painting them exclusively as alcoholics and drug addicts, lazy to find work, is misinformed and incorrect. The homeless population simply does not get enough thought in plans of making a city inclusive.

What happens to the homeless as cities increasingly face the brunt of climate change like flooding in Bengaluru, intense cold and heat in Delhi? Such questions are seldom asked and answered. Welfare schemes and policies on livelihood and housing too, like the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY), are not formulated to include this demographic.

All photos by Ashwin Sharma

(Nangsel Sherpa is an independent researcher. Pragati K.B. is an independent journalist currently reading for a master’s degree in Social Anthropology at the University of Oxford. This article was written with support from Asia Pacific Forum on Women Law and Development (APWLD). Views expressed are the writers’ own.)