Javed Akhtar On His Journey Through Life

Book Review

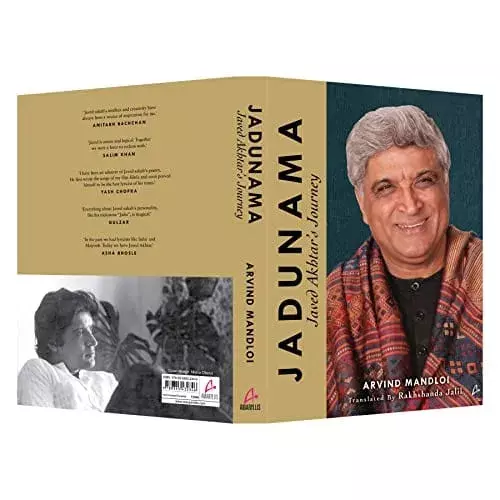

Much of what Javed Akhtar has said to the media during a career spanning some six decades is now saved in the pages of J’adunama: Javed Akhtar’s Journey’.

The 345-page ‘Jadunama’ is as full bodied as the journey of Jadu, one of the country’s most interesting writer, poet, lyricist and political activist.

The word ‘jadu’ means magic in Urdu while ‘nama’ is a farsi word for tales, or memoir. Jadu was the name originally given to Javed by his poet father Jan Nisar Akhtar.

When Javed was born on January 17 1945, Jan Nisar had rushed to the Kamla Hospital in Gwalior from the office of the Communist Party. At the hospital his friends reminded Jan Nisar of the lovely poem that he had written for his bride where he says that every moment after his wedding will be the story of some magic or the other: ‘lamha lamha kisi jadu ka fasana hoga…’

At that moment Javed’s birth had seemed like magic, and Jan Nisar immediately named his first-born Jadu. When it was time for the boy to be admitted in school, Jadu had sounded too informal and he was renamed Javed, meaning eternal. The meaning of Akhtar is star.

The day Javed was born, Jan Nisar was asked to follow the tradition of reading the call of prayer into the ear of the newly born baby. But Jan Nisar’s belief was different. In his hand he had held the manifesto of the Communist Party which he said he would read instead into the ear of the infant.

For the same reason perhaps, Javed grew up insisting that he is an atheist. He writes: “My name is Javed Akhtar. I have no religious belief. I have no faith in spirituality either...

“Today when I look back at my life after so many years, it seems, this river-coming down the mountains like a waterfall, dashing against rocks, finding its way through boulders, gurgling, twisting and turning, creating many a whirlpool along the way, running swiftly and sometimes cutting away at its own sides-has come into the plains and become deep and peaceful.

“Then, the thought occurs to me that I haven’t done even one fourth of what I could have done. And then the restlessness created by this thought refuses to leave me.”

Javed’s childhood was sad. He was eight years old when his mother passed away. His parents were married for barely a decade out of which time they mostly lived separately. His mother Safiya was a wonderful letter writer and she would write letters nearly every day.

In 1947 she wrote in a letter to her husband: “Jadu’s antics cannot be described they can only be seen. He is always happy, and talks nonstop. If one were to ask him, who is your grandfather, the answer is: ‘Stalin’. And the name of your paternal uncle (chacha)? ‘Chacha Dhalib’, he lisps, meaning Ghalib. He talks about his Chacha Ghalib all the time. In fact, he goes around dancing, holding a portrait of Ghalib.”

His mother had also predicted that if Jadu were to get entangled in poetry, of which there is a very real likelihood, then be warned that for the next seven generations no one will thrive in our family and only the Red Revolution can save us from calamity.

Javed has often said that if he had not spent the years he did in Lucknow, he could not have written poetry. He found that poetry was in the air in Lucknow, imperial capital of the former kingdom of Avadh.

Majaz, his maternal uncle is considered one of the greatest Urdu poets of the 20th century, and his paternal grandfather Muztar Khairabadi wrote: “na kisi ki aankh ka noor hoon, na kisi ke dil ka qarar hoon, jo kisi ke kaam na aa saka maiin woh ik mushte-e-ghubar hoon.”

These poetic lines bemoaning a loveless life were credited to Bahadur Shah Zafar, last Mughal Emperor till Javed proved that it was written by his grandfather.

After the death of his mother, Javed had lived with his maternal grandparents in Lucknow where he had played cricket all day with his younger brother Salman. He had spent his pocket money on buying brightly-coloured toffees in the morning and in the evening, he would enjoy a plate of the finger licking, lip smacking snacks or ‘chaat’ sold on the footpath across the street from the home of his grandparents.

The family cook had two daughters called Chhutkaniya and Badkaniya who were Javed Akhtar’s playmates. Chhutkaniya is quoted in the book as saying that in his childhood, Javed used to play rowdy games with her.

“But then he could also charm everyone. He was very naughty. The two of us used to climb the guava tree and pluck the guavas. He would never sleep during the day. He would come home and fling his satchel aside.

“He barely studied. He used to sit down with us and tell stories. He would always say that when I make a movie, it will be with a lot of fight sequences. And you, Chhutkaniya, must go and see it. He never looked sad. He was always acting alone. Years later, when he came, he sent for me. He cried a lot,” she said.

Javed’s youth was spent in many cities. While in Aligarh Farhan Mujib was one of his closest friends. Recalls Farhan: “When we were 13 years or 14 years old and Jadu was here, anyone could tell that he was a different sort of a boy…

“Every one could tell that he was different from the rest, one who would not follow the straight and narrow path. I met him next in 1963 when he visited Aligarh for a few days, and thereafter in 1973, and then in 1977 when we spent a month together in England. After that we kept meeting regularly.”

Javed graduated from Saifa College in Bhopal where he writes he had lived off the kindness of friends. In the second year of college, he had shared a room with a friend called Ejaz.

“Ejaz studies and gives tuitions to get by. All our friends call him ‘Master’. I have fought with Master over something. We are not talking to each other. Therefore, these days I am not asking him for money. I take whatever I need from his pant that is hanging from a peg on the wall in front of me. Sometimes he leaves a rupee or two by my bedside without saying a word,” he writes.

In 1964, Javed travelled to Mumbai to realise his dream of directing a film. He had 27 paise in his pocket. For two years he was homeless and found odd jobs in the film industry.

Then he met Salim Khan who made up fantastic stories. Together they wrote the screenplay of a film called Adhikar with Ashok Kumar and Nanda in the lead. But their names were not mentioned in the credits of the film.

Writes Salim Khan: “We met when we were both struggling. We had come from the same state: Madhya Pradesh, he from Bhopal and I from Indore. Javed used to live with some friend when he began to come to my house in Mumbai; perhaps he was a paying guest.

“I could see that he had talent, talent that should come to the fore. Though his ambition then was to become a director, I felt he would be a better writer. I was writing a script at that time. He began to help me. I then thought why should I take help; why shouldn’t the two of us work as partners? And we began to work as partners. Our team was a natural one.”

After having spent nearly six decades in the film industry, what Javed admires most about the industry is that it is not communal or sectarian. In fact, the film industry cannot afford to be communal.

Every person who is part of a film is always united and has only one purpose in mind that their film should succeed. Nothing else matters. This is a lesson all Indians can learn from the film industry. If every Indian was to decide that our country should become a superhit place then no citizen can afford to be communal and sectarian over region, language, religion or caste.

Because everyone would like to make the country a superhit. If citizens want to get entangled in communalism and sectarianism then it means that they are not interested in making the country a superhit. Period!

Javed had first narrated his journey to Arvind Mandloi for a book in Hindi titled ‘Jadunama: Javed Akhtar Ek Safar’ that has now been translated into English by Dr. Rakhshanda Jalil.

Jadunama: Javed Akhtar’s Journey

Published by Amaryllis

Price Rs 2999.