Mrs. Chatterjee Versus Norway: A Topical Reading Of ‘Mother India’

The story made international headlines a decade ago, and the Indian media often gave a different version

“Based on a true story” is like a double-edged sword, because the perspective of the film narrating one side of the story might create issues with the other side. There are those who believe that the word “truth” has many faces. But as far as ‘Mrs. Chatterjee Versus Norway’ goes, let us accept the story as the “truth.”

The story made international headlines around a decade ago and was specially focussed on by the Indian media which often gave a different version. Taking this as the “truth” let us take a look at the character of Mrs. Chatterji as today’s version of ‘Mother India’. Is she one?

Thematically, ‘Mother India’, made in 1957, is one of the most successful as well as one of the most idealistic Indian films. It emblematised the mother as a metaphor for respectability and sacrifice. Author Gayatri Chatterjee quotes a comment on how contemporary critics lauded the film as being about a mother ‘round who revolves everything that is sacred and glorious in our culture, tradition and civilization’. Adjusted for inflation, ‘Mother India’ still ranks among all-time box office hits.

Unlike the all-powerful, omniscient Durga, Radha of ‘Mother India’ is as vulnerable to the assaults of destiny as any ordinary woman. The retribution comes much later. In the final analysis, Radha does live through all this chaos to see her own triumph of Good over Evil. But she has to kill her own son Birju, to achieve this.

She is a loser in the battle of life in her role of natural motherhood because of her four sons, only one survives. Ironically, the only son who loved her with a fierce, almost passionate intensity, dies by her own hands. The camera, in a reverse shot, focusses on his bloodied hands which slowly open up in death, releasing his mother's beloved kangans (bangles) which the moneylender had held on to for long.

Radha just slipped into her role of the sacrificing mother and martyred woman who the village vested with the title of “Mother” not once wondering whether she truly wished that title or not.

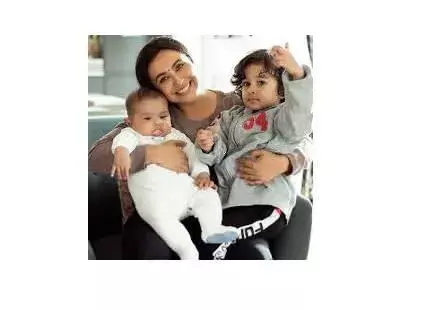

But in 2023, Mrs. Debika Chatterjee (Rani Mukherjee) is not one to take things lying down. On the contrary, she is determined to keep control over her two little children, who the Norwegian government’s Child Care service is determined to take away and place in foster families. Why should Norway pay a hefty amount to foster parents when natural parents are alive and willing to take care of the children? This remains an elusive question in the film.

Debika cannot speak neither good English nor good Hindi but manages with her pidgin linguistic command trying to mix these with her own mother tongue Bengali to fight for her children. They were snatched away right from under her nose. Why? Because she feeds them with her fingers, puts kohl in their eyes with a dot on their cheek, which is a part and parcel of Indian mothers’ caring for their children. One of the children is just five months old.

Two officers visit their house for 10 days and report that both parents are incapable of raising their children. The two stern-looking Norwegian women are even appointed to watch Chatterjee breastfeed her little one. “I used to feel awkward to begin with but since they are both ladies, I got comfortable after some time,” said Chatterjee in her interview with the authorities, the first of many interviews in Norway.

Her husband (Anirban Bhattacharya) seems more interested in acquiring Norwegian citizenship which may be delayed or halted if his wife is so adamant of not allowing the state to take her kids away. One critic has questioned Rani’s portrayal as being overly loud and cranky and hysterical, but this is explained by the simple logic that women’s voices can be heard only when they scream and cry loudly.

But there is another problem here. Mothers who shout, scream, roll over on the streets when pushed away from the speeding car carrying her kids away, they are, like Debika Chatterjee, labelled “mentally unfit” to look after their kids. Chatterjee’s own husband backs this labelling. She “kidnaps” her kids and flees to the neighbouring country but is caught and once again, the kids are snatched away from her.

How Chatterjee fights her case for the custody of her own children makes for the second half of the film. The kids are handed over to her brother-in-law in Kolkata for a hefty price, which makes her in-laws and husband happy.

But not one to give up her fight for her own children, Debika fights a court case and wins it, thanks to the lawyer, a brilliant performance by Jim Sarbh who admits without hesitation that Mrs. Chatterjee will never ever accept money for her children, investing the character with layers of multiple emotions. The judge (Barun Chandra) asks for an audience with the kids. Why? Is this permitted by law? We do not know.

One lapse is that the kids do not seem to have grown over three years. Just once the little girl is captured walking in halting steps towards her mother. It is a touching scene.

The members of her husband’s family are just too negative to ring true but Sagarika, the original Mrs. Chatterjee insists it is true. The music could and should have been in a lower key in terms of the melody, the positioning and decibels.

Anirban Bhattacharya does a wonderful debut in Bollywood in a negative role as Debika’s husband. The camera wanders across the map from Kolkata to Norway bringing out the cultural conflicts the immigrants must suffer, especially when they have come with the idea of settling down permanently.

But it is Rani Mukherjee who blends into the character of Debika as if she is born Debika and is not actually “acting her out.” But one is not surprised because Rani has acquired a mastery in performing in films without a hero image. She has proved time and again over the past decade that she does not need a hero or anyone else to lean back on.

Beginning with ‘Who Killed Jessica Lal’ followed by ‘Black, Mardani 1 and 2’, and ‘Hichki’, there is no Indian actor, male or female, who can carry a two-hour-plus film completely on her own shoulders without any make-up, glitzy costumes, warts and all which bring out her complete attention to get back the custody of her little kids. Rani Mukherjee does not need the coating of glamour and chutzpah. This film at least, should get her the National Award that has been eluding her for years at a stretch.

Having said that, even today, Radha of ‘Mother India’ offers the Indian audience a sort of a warped role model, not to imitate, but perhaps to dream about and to idolise. Sadly, ‘Mother India’ has been less attractive as the survivor than as the sacrificing woman.

After Mehboob Khan’s blockbuster, the saleability of anguished motherhood resulted in shallow clones… a widow or an abandoned woman who stitches clothes on a vintage sewing machine or works in a quarry/construction site to educate her child, usually the hero. As per the dictates of the plot, she is sick or dies of consumption and coughing fits, or is alive and healthy to feed him gajar ka halwa.’

The mother-figure in subsequent films was idolised and idealised but deprived of authority and agency. Not just selfless, she is self-less, a hollow symbol to be worshipped; she is asexual and inviolate. Constructed through the gaze of her husband, sons, in-laws, and neighbours, and usually silent about her own desires, her Self was more an absence. The recurrent visual motif of the ideal mother’s pallu-covered head is a metaphor for this veiling of the self behind customs and traditions.

Written by Sameer Satija, Ashima Chibber, and Rahul Handa, and directed by Ashima Chibber, ‘Mrs. Chatterjee Vs Norway’ could be termed a universal film for its diversity over a mother's issue which may help in doing away with eulogising Radha of Mother India. Debika Chatterjee is more a “today” mother, practical, hysterical and real. Hats off Rani.