Pillars Of Parallel Cinema

A chronicle of 50 path-breaking Hindi films

“To make great movies, there is an element of risk. You have to say, well, I am going to make this film and it is not really a sure thing”: Francis Ford Coppola.

Filmmaker Ketan Mehta became the jury chairman of the 69th National Film Awards in India. After the awards were declared, he said: “Congratulations… heartfelt congratulations to all the winners of the National Award. May Indian cinema flourish in the future.”

His congratulatory message was taken with a big pinch of bitter salt.

Mehta headed a jury which also bestowed the prestigious award, the Nargis Dutt Best Feature Film on National Integration to Vivek Agnihotri for ‘The Kashmir Files’. Even an eclectic student of cinema would dub the film as lacking basic elements of cinema aesthetics, if not, devoid of all ethics.

The film was backed by the ruling regime in Delhi and the Sangh Parivar, even as they celebrated Islamophobia in a similar propaganda film, ‘The Kerala Story’.

International award-winning filmmaker, Nadav Lapid, jury head of the International Film Festival of India (IFFI), had a different opinion of this film. At the closing ceremony of the festival, he said, “That felt to us like a propaganda, a vulgar movie, inappropriate for an artistic, competitive section of such a prestigious film festival.”

Those who know Ketan Mehta’s work in cinema over the years, and those who still make meaningful movies, were surprised and shocked. This is the man who has made brilliant films like ‘Mirch Masala’ and ‘Maya Memsaab’. His film, ‘Bhavni Bhavai’, had earlier won the same award, as did a classic of world cinema, ‘Garm Hawa’ by M.S. Sathyu.

Comparing ‘The Kashmir Files’ with this legacy of great cinema was like turning the entire genre of outstanding parallel cinema upside down.

Predictably, banker-turned-filmmaker, O.P. Srivastava, while documenting 50 path-breaking Hindi films, in his recent book, ‘Pillars of Parallel Cinema’, has listed this Ketan Mehta film as one of the finest.

He writes: “‘Mirch Masala’ is a searing critique of patriarchy and the men who abuse their power by denying women their rightful place in society.

“The film grants its oppressed subjects poetic justice in the end when the subedar, who could not be defeated by the village men, is brought to his knees by the collective strength of the women, signifying a new awakening in the patriarchal village – a step towards women’s emancipation in India.”

The film has stellar performances by Smita Patil, who leads the ‘hot spice rebellion’, apart from Om Puri, Naseeruddin Shah, Ratna Pathak, Supriya Pathak and Deepti Naval.

In the art-house hall of fame of parallel cinema in India, there are films which are legendary and known for their directorial craft, script, cinematography, music and performances. They are etched in the history of film-making in India as great cinema.

However, there are several brilliant movies which stirred the cinematic conscience, and struck a deep aesthetic chord, but are not really remembered or glorified as they should be. In that sense, Srivastava has done a fabulous job in documenting these 50 path-breaking Hindi films.

The whole world knows the classical genre which Satyajit Ray unleashed after his film made on a shoe-string budget, ‘Pather Panchali’. Other films with creative excellence followed, ‘The Apu Trilogy, Devi, Nayak, Mahanagar, Hirok Rajar Deshe, Pratidwandi’, among others.

Film-lovers still remember ‘Shatranj Ke Khilari’, penned by another great, Munshi Premchand, with excellent performances by Saeed Jaffrey and Sanjeev Kumar, playing chess on the shore of a sad Gomti river, as the British forces invaded Lucknow.

However, how many of us really remember ‘Sadgati’, once again penned by Munshi Premchand? Ray described Sadgati as “a deeply angry film… not the anger of an exploding bomb, but a bow stretched taut and quivering.”

What would seem impossible in contemporary India now, Doordarshan produced this 50-minute film for television and it was released in the spring of 1984. Ray composed the background music, as he did for some of his other films, “using local sounds, including the tinkle of cowbells,” writes Srivastava.

Om Puri and Smita Patil play a Dalit couple. They seek an auspicious date for the engagement of their daughter, and thereby the priest asks them to cut a huge block of wood. Under a scorching summer sun, emaciated and malnourished, exhausted with the hard labour, the male protagonist dies.

In a shocking scene, held-back as Ray does when it comes to extreme tragedy, the body lies outside the priest’s house, and the villagers refuse to touch it. The dead man is a Dalit.

“Finally, the priest himself ties a rope to Dukhi’s (Om Puri) ankle, drags the body outside the village limits under the cover of twilight and leaves it there. He returns home and purifies the place where the body had lain by sprinkling holy water and reciting mantras, symbolically performing Dukhi’s last rites and providing him an ironic ‘sadgat’,” writes Srivastava.

‘Bhuvan Shome’ was Mrinal Sen’s ninth film, released in May 1969. Ace cinematographer KK Mahajan shot the film. This quiet and slow film, made on a budget of less than Rs 2 lakh, was based on a short story by Banaphul (Balai Chand Mukhopadhayay) and was funded by the Film Finance Corporation.

The sensitive film with unknown actors arrived amidst a host of popular Bollywood movies and it seemed it would not stand a chance in terms of audience reception. Among other films, there was ‘Do Raaste’ starring Rajesh Khanna and Mumtaz, ‘Jeene Ki Raah’ starring Jeetendra and Tanuja, ‘Aya Sawan Jhoom Ke’ with Dharmendra and Asha Parekh and ‘Ek Phool Do Mali’ with Sanjay Khan and Sadhana.

Indeed, amidst these successful movies, this Hindi film reached out to a discerning and restless audience which was yearning for meaningful cinema and stories. The film arrived amidst the turmoil of the early phase of the Naxalite movement and the universal disappointment on the betrayal of the values and vision of the Indian freedom movement.

Interestingly, Srivastava writes, Amitabh Bachchan did the voice-over for the story. He was reportedly reluctant to take a pie for his work, but was eventually persuaded to accept Rs 300.

This was Utpal Dutt’s first Hindi film, with an exemplary role played by young Suhasini Mulay, with her “magically captivating smile”. Dutt got the National Award for Best Actor, while the film won the Best Director and Best Feature Film awards.

A sad short story by Mohan Rakesh, ‘Uski Roti’. Directed by Mani Kaul. Cinematography, once again by K.K. Mahajan. Writes Srivastava, “It is a film about a young Punjabi woman, Bhalo, who goes to the bus stop every day to give her husband, roadways driver Sucha Singh, his roti.

While Bhalo is restricted to a monotonous and laborious routine in the village, waiting for her husband to come home, her husband spends his time drinking, playing cards and spending time with another lady in nearby Nakodar.

True to its setting, the film was shot in a village in Punjab.” According to Srivastava, the film’s cinematic idiom was inspired by famous German playwright Bertolt Brecht, and French filmmaker Robert Bresson.

In 1980, a remarkable film arrived which broke the threshold of intense angst and anger. The film was directed by Govind Nihalani, his debut film; he had earlier done the cinematography for the films of Shyam Benegal (Ankur and Nishant) with scripts by Vijay Tendulkar and Satyadev Dubey, big names in Indian theatre. Nihalani went on to make non-conformist movies like ‘Ardh Satya’ (a box-office hit), ‘Junoon’, ‘Party’ and ‘Tamas’.

The 144-minute film has Om Puri in the lead with no dialogue. He is silent all through the film, his face, eyes, fingers, making the body language intense. Located in a tribal landscape, and based on a true incident, the film ripped apart the farce of freedom and justice in a democracy where the margins were ritualistically being brutalised and crushed.

Writes Srivastava, “The oppressed don’t plead their case. Their place in society, dealing with injustice and oppression, is something they have grown up with. Here, the oppressed victim is so traumatised by the excessive oppression and violation of his humanity that he does not utter a single word for almost the entire length of the film. The burden of his angst is carried entirely by his fiery eyes and his conscience.”

Like ‘Ardh Satya’, with Om Puri yet again as the protagonist, along with Smita Patil, Aakrosh was a big success, even among the mainstream audience, something simply impossible to conceive in the cinema of contemporary times. It became a hit amidst big star box-office hits like ‘Qurbani’ (with Feroz Khan, Zeenat Aman and Vinod Khanna), ‘Karz’ and ‘The Burning Train’.

In his memoirs, ‘And Then One Day’, Naseeruddin Shah has written, “Om’s blazing salt-of-the-earth intensity finally caught the eyes of many a filmmaker, but it was Govind Nihalani, who, first, recognized the magnetic simplicity in his screen presence and cast him in Aakrosh as the anguished, silent, adivasi wrongly accused of his wife’s murder. Om’s definitive film performance.”

Gautam Ghosh, a Bengali filmmaker, made a classic called ‘Paar’ (The Crossing), based on a Bengali story by Samaresh Basu, set in rural Bihar, with Shabana Azmi and Naseeruddin Shah. He also did cinematography and music.

Srivastava writes, “‘Paar’ is a story of human endurance, a person’s courage to fight against the caste-based oppression, perpetuated in our society, especially in rural India. It is a cinematic expression of the voice of resistance…

“… The hallmark of the film is this 12-minute sequence, where Shah and Azmi swim through the flowing river to drive the herd of pigs to the other side. The scene has made the film unforgettable; even today, filmmakers wonder at the audacity of Ghose’s method and the actors’ dedication to maintain authenticity and sensitivity in this scene.

“The squealing of the pigs was real. The heads rubbing with the snouts of the pigs in the middle of the choppy waters are the heads of the two actors themselves…”

Said Ghosh, “It was a great challenge. We were courageous and that is why we could do it. The breed of actors (Shah, Azmi, Puri, all of them, young FTII pass-outs) were unbelievable – they said the risk was not a factor.”

The film was nominated for the Golden Lion Award in 1984 at the Venice International Film Festival, where Shah was awarded the Voli Cup for Best Actor. The film also won the National Award for Best Feature Film in 1985, with Shah and Azmi winning the best actor and best actress awards. The film won the Filmfare Award in 1986 for Best Screenplay for Gautam Ghosh and Swapan Sarkar.

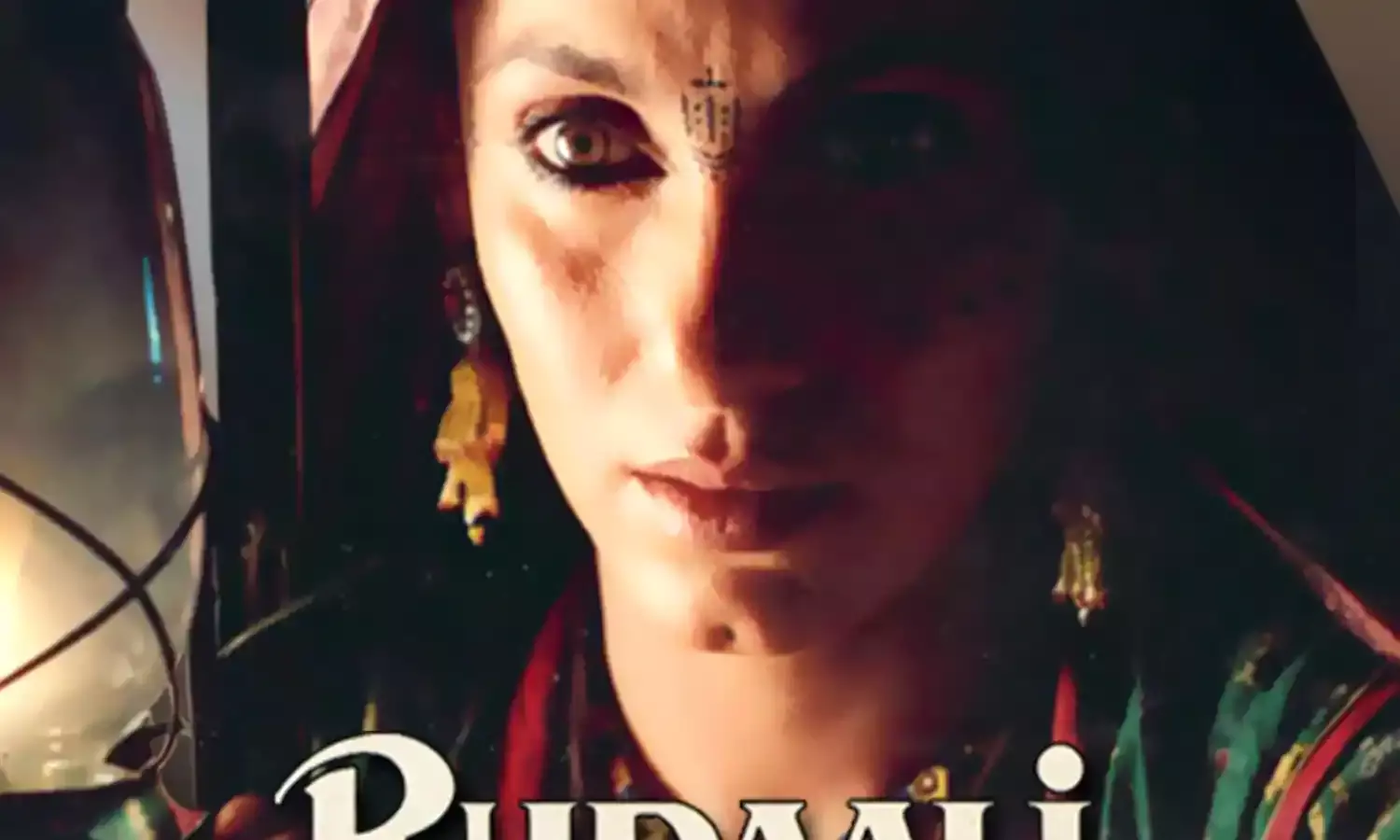

Great Bengali writer Mahashweta Devi wrote ‘Rudaali’ and Gulzar did the script. This extraordinary film, located in the magical landscape of Rajasthan, was made by Kalpana Lajmi in 1993.

The story is woven around the haunting ritual of ‘rudaali’, whereby Dalit women are hired to mourn the deaths of upper caste men, precisely because women of that caste were prohibited to enter the public space.

This film too arrived amidst Bollywood commercial blockbusters, ‘Khalnayak’ with Madhuri Dixit and Sanjay Dutt, ‘Darr’ and ‘Baazigar’ marking the advent of superstar Shahrukh Khan in Bombay cinema, and Khuda Gawah starring Amitabh Bachchan.

This was a phase of great difficulty for meaningful cinema, while it gave way to what is called the ‘middle-of-the-road’ cinema with filmmakers like Basu Bhattacharya and Hrishikesh Mukherjee rolling out commercially successful films for family audiences.

Dimple Kapadia and Rakhi were brilliant in ‘Rudaali’, which also had Amjad Khan, a fabulous actor, in a supporting role. The songs of the film became a household hit, running on All India Radio and Vividh Bharti.

Composed by Bhupen Hazarika, ‘Dil Hoom Hoom Kare’, based on Raga Bhopali, became a super hit. Dimple Kapadia won the National Award for Best Actress, and the Best Music Director award went to Hazarika.

Srivastava writes, “In film, mirrors are used to depict moments of reflection, physical and emotional, as well as moments of deceit, deception, dejection, juxtaposition, contrast and comparison, distortion, delusion, breaking down and breaking through. The 50-write-ups in this book are an attempt to break through these films in retrospect.”

This well-researched book, which is a mirror to the social and political reality of our past and present, showcases other aesthetic breakthroughs in Hindi cinema, such as ‘Ashad Ka Ek Din, Maya Darpan, Manthan, Bhumika, 27 Down, Mrigyaa, Shatranj Ke Khiladi, Chirutha, Mohan Joshi Haazir Ho, Om Dar Be Dar, Party, Massey Saab, Pestonjee, Tamas, Suraj Ka Saatwa Ghoda’ and ‘Mammo’, among others.

Author O.P. Srivastava has made feature documentaries such as ‘Life in Metaphors: A Portrait of Girish Kasaravalli’, which won the National Film Award for the Best Biopic in 2015, among others.

Pillars of Parallel Cinema: 50 Path-Breaking Hindi Films

Author: OP Srivastava

Publisher: Authors Upfront

Rs 597

Pg 284