Subhas Chandra Bose And Emilie Schenkl - A Love Story

The two met in Vienna, fell in love and got married

Much talk about Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose on the eve of the Lok Sabha elections 2024 has transported me back to Vienna, Austria.

I lived in Vienna between 1982 and 2012, and collected a volume of stories about people with interesting Indian connections.

I got to know Emilie Schenkl, the widow of Bose. There was Mirabehn, a Gandhian. Mirabehn was the name given by Mahatma Gandhi to Madeleine Slade, a British follower who was part of the Indian freedom struggle since 1925.

After Gandhi’s assassination in Delhi, Mirabehn had lived in Kashmir, Kumaon and Garhwal. She observed the destruction of the forests and wrote about it in an essay titled Something Wrong in the Himalaya. In 1960 she moved to Vienna where she passed away in 1982 at the age of 90 years.

Crystal Pai was an Austrian socialist, and the widow of the Indian socialist leader Nath Pai. In 1954 Pai was elected the first non-European president of the International Union of Socialist Youth that had its office in Austria. Pai had died suddenly in 1971 at the age of 48 years.

The Praja Socialist Party leader was called ‘the pearl in Parliament’. Pai is remembered for not missing a single opportunity to take on his opponents, particularly the ruling party in the Lok Sabha.

Quotations flowed out of him in English, Marathi and Sanskrit. Pai’s speech was laced with stories and anecdotes, with legal arguments and a flourish of emotional outbursts. Above all there was the beauty of the language used by him with a superb power of expression.

Michaela Sarma’s husband was an interpreter in Hitler’s army. He was the link between Bose’s Indian National Army (INA) and the German army during World War II. Sarma was the secretary of Thea von Harbou, a German actress in Berlin who was close to Hitler.

Harbou was married to the Austrian film director Fritz Lang. She had later married the Indian journalist Ayi Ganpat Tendulkar.

Lang had fled Germany after a screening of his film “The Testament of Dr Mabuse” was cancelled by Hitler’s chief propagandist Joseph Goebbels and it was later banned. Goebbels said that the film was banned because it showed that an extremely dedicated group of people are perfectly capable of overthrowing any state with violence, and that the film posed a threat to public health and safety!

In the 1980s Sarma was employed at the Indian Embassy in Vienna. Every time she was asked whether she and Harbou had been Nazi sympathisers she always said no, they were not.

After Bose fell out with Gandhi, he resigned from the Congress in 1939. He returned to Vienna in 1941 during World War II to seek help from Nazi Germany against the British in India.

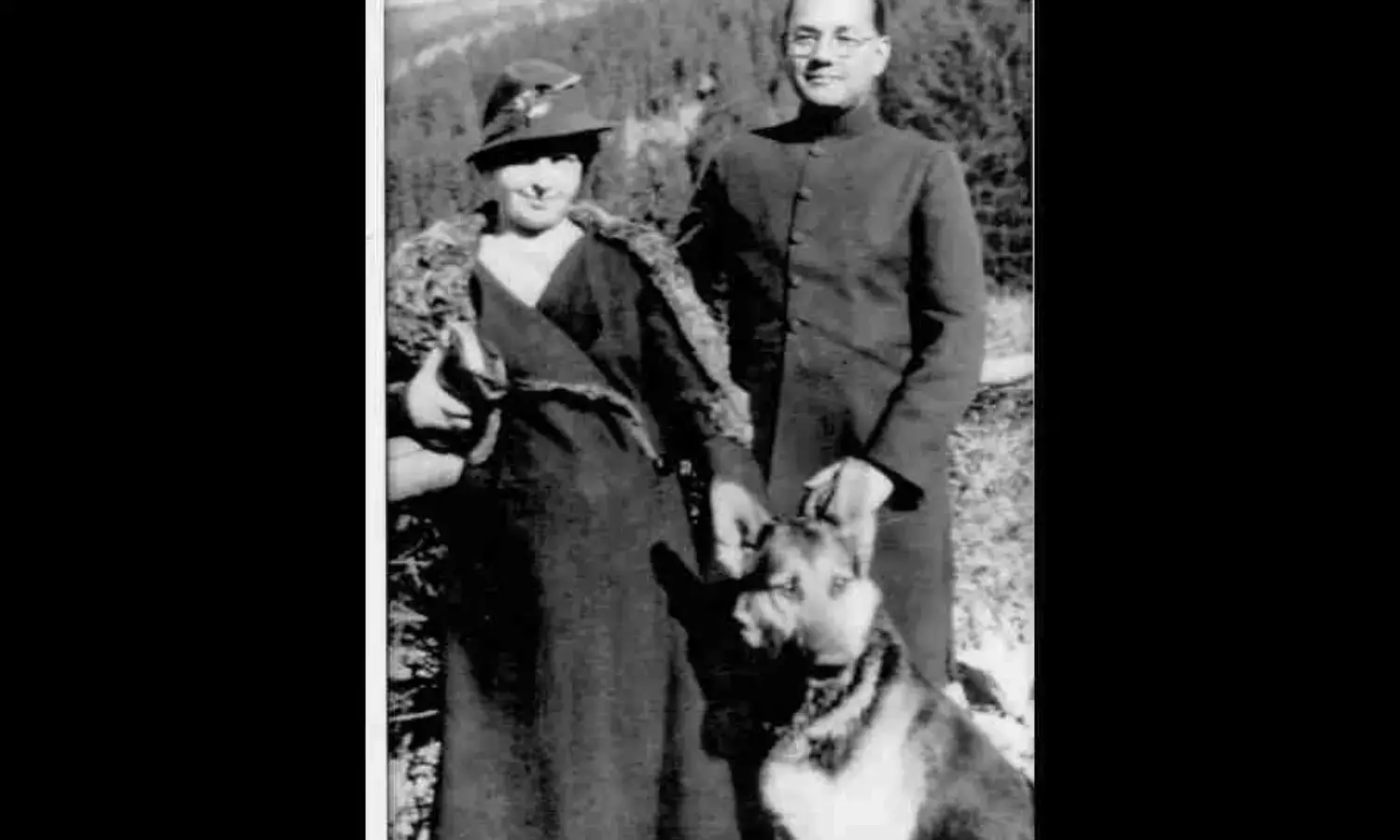

Bose had visited Austria and Germany for the first time in 1933 for medical treatment. Bose met the 24-year-old Schenkl in June 1934 through a mutual friend and a medical doctor in Vienna called Dr Mathur.

Bose was more than a decade older to Schenkl and had a contract with a British publisher to write a book on the freedom struggle in India. He needed a stenographer and hired Schenkl as his secretary who helped him write “The Indian Struggle”. Soon the two fell in love. In 1936 Bose returned to India.

He wrote to Schenkl that even an iceberg sometimes melts, and so it is with me now.” He had “already sold” himself to his “first love”, his country to whom he had to return.

Wrote Bose, “I do not know what the future has in store for me. Maybe, I shall spend my life in prison, maybe, I shall be shot or hanged. But whatever happens, I shall think of you and convey my gratitude to you in silence for your love for me.

“Maybe I shall never see you again, maybe I shall not be able to write to you again when I am back, but believe me, you will always live in my heart, in my thoughts and in my dreams. If fate should thus separate us in this life, I shall long for you in my next life.” He had “never thought before that a woman’s love could ensnare” him.

On his arrival in Mumbai in April 1936, Bose was arrested and kept in solitary confinement till December 1936. In one of the letters Bose wrote to Schenkl he requested her to find the original German text of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s romantic poem inspired by Kalidas’s “Shakuntala”.

“Letters to Emilie Schenkl” is a collection of letters first published in 1994 to mark the 60th anniversary of the first meeting between Schenkl and Bose. All the letters that Bose wrote to Schenkl have survived but only 18 of her letters to Bose could be traced for publication in the same volume.

Before Schenkl passed away in 1996, I had asked her what she had to say to the followers of Bose who refused to believe that she was his wife?

“The trouble with people is that they forget that the person they adore is a human being. My husband was not a god, he was a human being,” said Schenkl. Questioned if she ever had doubts over the death of Bose in the aeroplane crash, Schenkl said that if her husband was alive she was sure that he would have come to her.

It was like the end of the world for Schenkl when on the evening of that August in 1945 she heard over the radio playing in her kitchen that Bose had been killed in an air crash in Taiwan.

Leaving her mother and sister speechless in the kitchen, Schenkl had gone to the bedroom where her three year old daughter Anita was asleep, and kneeling by the bed she had wept.

Bose had married Schenkl in 1937 but the couple kept their marriage a secret due to the politics of the time. Their daughter was born in November 1942 and was named Anita after the Brazilian revolutionary, and wife of the Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Garibaldi.

In 1941 Bose returned to Germany in the hope of getting help from the German Chancellor Adolf Hitler against the British in India. In Berlin the German Foreign Office had hosted Bose in a luxurious residence with a butler, cook, gardener, car and a chauffeur.

Some of the staff at the Special Bureau for India did not approve of Schenkl who had moved in with Bose in his Berlin home. The Information Department of the Foreign Office of Nazi Germany had established the Special Bureau for India in 1941 after Bose had asked for help for India against the British.

The responsibilities of the bureau had included the running of the Azad Hind Radio. The officials of the same bureau had first called Bose ‘Netaji’.

Schenkl had helped Bose in the day to day work at the Free India Centre that was given diplomatic status by Nazi Germany. The office of the Free India Centre was No 2A Lichtensteiner Allee in Tiergarten, but many meetings were hosted by Bose at his residence on Sophienstrasse, Charlottenburg in Berlin.

Schenkl never visited India and Bose had last seen his daughter Anita in Berlin around Christmas in 1942. The couple never saw each other again after February 1943.